Conducting a Literature Review

- Literature Review

- Developing a Topic

- Planning Your Literature Review

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Managing Citations

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Writing a Literature Review

Appraise Your Research Articles

The structure of a literature review should include the following :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Value -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

Reviewing the Literature

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what the articles are saying, but how are they saying it.

Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

- When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Tools for Critical Appraisal

Now, that you have found articles based on your research question you can appraise the quality of those articles. These are resources you can use to appraise different study designs.

Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (Oxford)

University of Glasgow

"AFP uses the Strength-of-Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT), to label key recommendations in clinical review articles."

- SORT: Rating the Strength of Evidence American Family Physician and other family medicine journals use the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) system for rating bodies of evidence for key clinical recommendations.

- The Interprofessional Health Sciences Library

- 123 Metro Boulevard

- Nutley, NJ 07110

- [email protected]

- Student Services

- Parents and Families

- Career Center

- Web Accessibility

- Visiting Campus

- Public Safety

- Disability Support Services

- Campus Security Report

- Report a Problem

- Login to LibApps

Best Practice for Literature Searching

- Literature Search Best Practice

- What is literature searching?

- What are literature reviews?

- Hierarchies of evidence

- 1. Managing references

- 2. Defining your research question

- 3. Where to search

- 4. Search strategy

- 5. Screening results

- 6. Paper acquisition

- 7. Critical appraisal

- Further resources

- Training opportunities and videos

- Join FSTA student advisory board This link opens in a new window

- Chinese This link opens in a new window

- Italian This link opens in a new window

- Persian This link opens in a new window

- Portuguese This link opens in a new window

- Spanish This link opens in a new window

Deciding what to include in your review through critical appraisal

Once you have narrowed down your pool of results, it's time to begin critically appraising your articles. Using a checklist helps you scrutinise articles in a consistent, structured way.

Questions to consider include:

- Are the aims of the study clearly stated?

- Is the study design suitable for the aims?

- Are the measurements and methods used clearly described?

- Are the correct measurement tools used?

- Are the statistical methods described?

- Was the sample size adequate?

- Are the methods overall described in enough detail that you could replicate the study?

- Does the discussion overall reflect the results?

- Who funded this study?

- What are the specific limitations of what can be concluded from the study?

Working through the questions will help you identify the strengths and weakness of each article, and also identify points to draw on when you write about the literature.

- DOWNLOAD THE CRITICAL APPRAISAL CHECKLIST

Additional critical appraisal checklists

REFLECT provides a checklist for evaluating randomized control trials in livestock and food safety.

CASP provides checklists for critical appraisal of studies related to health.

JBI provides checklists for critical appraisal of studies related to health.

Documenting critical appraisal decisions

As you closely examine full articles, you will be making judgements about why to include or exclude each study from your review. Documenting your reasoning will help you reassure yourself and demonstrate to others that you have been systematic and unbiased in your appr aisal decisions.

Keeping track of what you have excluded, and why, will be very helpful if you must defend your work—for instance, if your literature review is part of a dissertation or thesis.

Pulling all the literature you will include in your review into a single chart is a good way to begin to synthesise the literature.

- DOWNLOAD THE FULL TEXT SCREENING CHART

Best practice!

BEST PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION : If you include any direct quotes in your chart (or in any notes) be sure to use quotation marks so that you don’t later mistake the words for your own.

BEST PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION: The more carefully you record each of the steps of your process, the more easily reproducible it will be. This is especially important for research abstracts and articles found in conference proceedings.

- << Previous: 6. Paper acquisition

- Next: Further resources >>

- Last Updated: May 17, 2024 5:48 PM

- URL: https://ifis.libguides.com/literature_search_best_practice

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 20 January 2009

How to critically appraise an article

- Jane M Young 1 &

- Michael J Solomon 2

Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology volume 6 , pages 82–91 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

52k Accesses

100 Citations

448 Altmetric

Metrics details

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article

Critical appraisal provides a basis for decisions on whether to use the results of a study in clinical practice

Different study designs are prone to various sources of systematic bias

Design-specific, critical-appraisal checklists are useful tools to help assess study quality

Assessments of other factors, including the importance of the research question, the appropriateness of statistical analysis, the legitimacy of conclusions and potential conflicts of interest are an important part of the critical appraisal process

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Making sense of the literature: an introduction to critical appraisal for the primary care practitioner

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 2: systematic reviews and meta-analyses

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 1: randomised controlled trials

Druss BG and Marcus SC (2005) Growth and decentralisation of the medical literature: implications for evidence-based medicine. J Med Libr Assoc 93 : 499–501

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Glasziou PP (2008) Information overload: what's behind it, what's beyond it? Med J Aust 189 : 84–85

PubMed Google Scholar

Last JE (Ed.; 2001) A Dictionary of Epidemiology (4th Edn). New York: Oxford University Press

Google Scholar

Sackett DL et al . (2000). Evidence-based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM . London: Churchill Livingstone

Guyatt G and Rennie D (Eds; 2002). Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: a Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice . Chicago: American Medical Association

Greenhalgh T (2000) How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-based Medicine . London: Blackwell Medicine Books

MacAuley D (1994) READER: an acronym to aid critical reading by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 44 : 83–85

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hill A and Spittlehouse C (2001) What is critical appraisal. Evidence-based Medicine 3 : 1–8 [ http://www.evidence-based-medicine.co.uk ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Public Health Resource Unit (2008) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . [ http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/CASP.htm ] (accessed 8 August 2008)

National Health and Medical Research Council (2000) How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature . Canberra: NHMRC

Elwood JM (1998) Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials (2nd Edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2002) Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence? Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 47, Publication No 02-E019 Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Crombie IK (1996) The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: a Handbook for Health Care Professionals . London: Blackwell Medicine Publishing Group

Heller RF et al . (2008) Critical appraisal for public health: a new checklist. Public Health 122 : 92–98

Article Google Scholar

MacAuley D et al . (1998) Randomised controlled trial of the READER method of critical appraisal in general practice. BMJ 316 : 1134–37

Article CAS Google Scholar

Parkes J et al . Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: cd001270. 10.1002/14651858.cd001270

Mays N and Pope C (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 320 : 50–52

Hawking SW (2003) On the Shoulders of Giants: the Great Works of Physics and Astronomy . Philadelphia, PN: Penguin

National Health and Medical Research Council (1999) A Guide to the Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines . Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

US Preventive Services Taskforce (1996) Guide to clinical preventive services (2nd Edn). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

Solomon MJ and McLeod RS (1995) Should we be performing more randomized controlled trials evaluating surgical operations? Surgery 118 : 456–467

Rothman KJ (2002) Epidemiology: an Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: sources of bias in surgical studies. ANZ J Surg 73 : 504–506

Margitic SE et al . (1995) Lessons learned from a prospective meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 43 : 435–439

Shea B et al . (2001) Assessing the quality of reports of systematic reviews: the QUORUM statement compared to other tools. In Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context 2nd Edition, 122–139 (Eds Egger M. et al .) London: BMJ Books

Chapter Google Scholar

Easterbrook PH et al . (1991) Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 337 : 867–872

Begg CB and Berlin JA (1989) Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst 81 : 107–115

Moher D et al . (2000) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Br J Surg 87 : 1448–1454

Shea BJ et al . (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 7 : 10 [10.1186/1471-2288-7-10]

Stroup DF et al . (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283 : 2008–2012

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: evaluating surgical effectiveness. ANZ J Surg 73 : 507–510

Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 274 : 1456–1458

Schulz KF et al . (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273 : 408–412

Moher D et al . (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology 1 : 2 [ http://www.biomedcentral.com/ 1471-2288/1/2 ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Rochon PA et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ 330 : 895–897

Mamdani M et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 330 : 960–962

Normand S et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ 330 : 1021–1023

von Elm E et al . (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335 : 806–808

Sutton-Tyrrell K (1991) Assessing bias in case-control studies: proper selection of cases and controls. Stroke 22 : 938–942

Knottnerus J (2003) Assessment of the accuracy of diagnostic tests: the cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol 56 : 1118–1128

Furukawa TA and Guyatt GH (2006) Sources of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies and the diagnostic process. CMAJ 174 : 481–482

Bossyut PM et al . (2003)The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 138 : W1–W12

STARD statement (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies). [ http://www.stard-statement.org/ ] (accessed 10 September 2008)

Raftery J (1998) Economic evaluation: an introduction. BMJ 316 : 1013–1014

Palmer S et al . (1999) Economics notes: types of economic evaluation. BMJ 318 : 1349

Russ S et al . (1999) Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 52 : 1143–1156

Tinmouth JM et al . (2004) Are claims of equivalency in digestive diseases trials supported by the evidence? Gastroentrology 126 : 1700–1710

Kaul S and Diamond GA (2006) Good enough: a primer on the analysis and interpretation of noninferiority trials. Ann Intern Med 145 : 62–69

Piaggio G et al . (2006) Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 295 : 1152–1160

Heritier SR et al . (2007) Inclusion of patients in clinical trial analysis: the intention to treat principle. In Interpreting and Reporting Clinical Trials: a Guide to the CONSORT Statement and the Principles of Randomized Controlled Trials , 92–98 (Eds Keech A. et al .) Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Medical Publishing Company

National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 89–90 Canberra: NHMRC

Lo B et al . (2000) Conflict-of-interest policies for investigators in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 343 : 1616–1620

Kim SYH et al . (2004) Potential research participants' views regarding researcher and institutional financial conflicts of interests. J Med Ethics 30 : 73–79

Komesaroff PA and Kerridge IH (2002) Ethical issues concerning the relationships between medical practitioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Med J Aust 176 : 118–121

Little M (1999) Research, ethics and conflicts of interest. J Med Ethics 25 : 259–262

Lemmens T and Singer PA (1998) Bioethics for clinicians: 17. Conflict of interest in research, education and patient care. CMAJ 159 : 960–965

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JM Young is an Associate Professor of Public Health and the Executive Director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney,

Jane M Young

MJ Solomon is Head of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre and Director of Colorectal Research at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney, Australia.,

Michael J Solomon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane M Young .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Young, J., Solomon, M. How to critically appraise an article. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6 , 82–91 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Download citation

Received : 10 August 2008

Accepted : 03 November 2008

Published : 20 January 2009

Issue Date : February 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Emergency physicians’ perceptions of critical appraisal skills: a qualitative study.

- Sumintra Wood

- Jacqueline Paulis

- Angela Chen

BMC Medical Education (2022)

An integrative review on individual determinants of enrolment in National Health Insurance Scheme among older adults in Ghana

- Anthony Kwame Morgan

- Anthony Acquah Mensah

BMC Primary Care (2022)

Autopsy findings of COVID-19 in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Anju Khairwa

- Kana Ram Jat

Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology (2022)

The use of a modified Delphi technique to develop a critical appraisal tool for clinical pharmacokinetic studies

- Alaa Bahaa Eldeen Soliman

- Shane Ashley Pawluk

- Ousama Rachid

International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy (2022)

Critical Appraisal: Analysis of a Prospective Comparative Study Published in IJS

- Ramakrishna Ramakrishna HK

- Swarnalatha MC

Indian Journal of Surgery (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Systematic Reviews & Evidence Synthesis Methods

Critical appraisal.

- Types of Reviews

- Formulate Question

- Find Existing Reviews & Protocols

- Register a Protocol

- Searching Systematically

- Supplementary Searching

- Managing Results

- Deduplication

- Glossary of terms

- Librarian Support

- Video tutorials This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Review & Evidence Synthesis Boot Camp

Some reviews require a critical appraisal for each study that makes it through the screening process. This involves a risk of bias assessment and/or a quality assessment. The goal of these reviews is not just to find all of the studies, but to determine their methodological rigor, and therefore, their credibility.

"Critical appraisal is the balanced assessment of a piece of research, looking for its strengths and weaknesses and them coming to a balanced judgement about its trustworthiness and its suitability for use in a particular context." 1

It's important to consider the impact that poorly designed studies could have on your findings and to rule out inaccurate or biased work.

Selection of a valid critical appraisal tool, testing the tool with several of the selected studies, and involving two or more reviewers in the appraisal are good practices to follow.

1. Purssell E, McCrae N. How to Perform a Systematic Literature Review: A Guide for Healthcare Researchers, Practitioners and Students. 1st ed. Springer ; 2020.

Evaluation Tools

- The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument (AGREE II) The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument (AGREE II) was developed to address the issue of variability in the quality of practice guidelines.

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM). Critical Appraisal Tools "contains useful tools and downloads for the critical appraisal of different types of medical evidence. Example appraisal sheets are provided together with several helpful examples."

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklists Critical Appraisal checklists for many different study types

- Critical Review Form for Qualitative Studies Version 2, developed out of McMaster University

- Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS) Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, et al. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016;6:e011458. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

- Downs & Black Checklist for Assessing Studies Downs, S. H., & Black, N. (1998). The Feasibility of Creating a Checklist for the Assessment of the Methodological Quality Both of Randomised and Non-Randomised Studies of Health Care Interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979-), 52(6), 377–384.

- GRADE The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group "has developed a common, sensible and transparent approach to grading quality (or certainty) of evidence and strength of recommendations."

- Grade Handbook Full handbook on the GRADE method for grading quality of evidence.

- MAGIC (Making GRADE the Irresistible choice) Clear succinct guidance in how to use GRADE

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools "JBI’s critical appraisal tools assist in assessing the trustworthiness, relevance and results of published papers." Includes checklists for 13 types of articles.

- Latitudes Network This is a searchable library of validity assessment tools for use in evidence syntheses. This website also provides access to training on the process of validity assessment.

- Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool A tool that can be used to appraise a mix of studies that are included in a systematic review - qualitative research, RCTs, non-randomized studies, quantitative studies, mixed methods studies.

- RoB 2 Tool Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Hróbjartsson A, Boutron I, Reeves B, Eldridge S. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials In: Chandler J, McKenzie J, Boutron I, Welch V (editors). Cochrane Methods. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 10 (Suppl 1). dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD201601.

- ROBINS-I Risk of Bias for non-randomized (observational) studies or cohorts of interventions Sterne J A, Hernán M A, Reeves B C, Savović J, Berkman N D, Viswanathan M et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions BMJ 2016; 355 :i4919 doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Critical Appraisal Notes and Checklists "Methodological assessment of studies selected as potential sources of evidence is based on a number of criteria that focus on those aspects of the study design that research has shown to have a significant effect on the risk of bias in the results reported and conclusions drawn. These criteria differ between study types, and a range of checklists is used to bring a degree of consistency to the assessment process."

- The TREND Statement (CDC) Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N, and the TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:361-366.

- Assembling the Pieces of a Systematic Reviews, Chapter 8: Evaluating: Study Selection and Critical Appraisal.

- How to Perform a Systematic Literature Review, Chapter: Critical Appraisal: Assessing the Quality of Studies.

Other library guides

- Duke University Medical Center Library. Systematic Reviews: Assess for Quality and Bias

- UNC Health Sciences Library. Systematic Reviews: Assess Quality of Included Studies

- Last Updated: Jul 12, 2024 8:46 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/systematicreviews

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

A guide to critical appraisal of evidence

Fineout-Overholt, Ellen PhD, RN, FNAP, FAAN

Ellen Fineout-Overholt is the Mary Coulter Dowdy Distinguished Professor of Nursing at the University of Texas at Tyler School of Nursing, Tyler, Tex.

The author has disclosed no financial relationships related to this article.

Critical appraisal is the assessment of research studies' worth to clinical practice. Critical appraisal—the heart of evidence-based practice—involves four phases: rapid critical appraisal, evaluation, synthesis, and recommendation. This article reviews each phase and provides examples, tips, and caveats to help evidence appraisers successfully determine what is known about a clinical issue. Patient outcomes are improved when clinicians apply a body of evidence to daily practice.

How do nurses assess the quality of clinical research? This article outlines a stepwise approach to critical appraisal of research studies' worth to clinical practice: rapid critical appraisal, evaluation, synthesis, and recommendation. When critical care nurses apply a body of valid, reliable, and applicable evidence to daily practice, patient outcomes are improved.

Critical care nurses can best explain the reasoning for their clinical actions when they understand the worth of the research supporting their practices. In c ritical appraisal , clinicians assess the worth of research studies to clinical practice. Given that achieving improved patient outcomes is the reason patients enter the healthcare system, nurses must be confident their care techniques will reliably achieve best outcomes.

Nurses must verify that the information supporting their clinical care is valid, reliable, and applicable. Validity of research refers to the quality of research methods used, or how good of a job researchers did conducting a study. Reliability of research means similar outcomes can be achieved when the care techniques of a study are replicated by clinicians. Applicability of research means it was conducted in a similar sample to the patients for whom the findings will be applied. These three criteria determine a study's worth in clinical practice.

Appraising the worth of research requires a standardized approach. This approach applies to both quantitative research (research that deals with counting things and comparing those counts) and qualitative research (research that describes experiences and perceptions). The word critique has a negative connotation. In the past, some clinicians were taught that studies with flaws should be discarded. Today, it is important to consider all valid and reliable research informative to what we understand as best practice. Therefore, the author developed the critical appraisal methodology that enables clinicians to determine quickly which evidence is worth keeping and which must be discarded because of poor validity, reliability, or applicability.

Evidence-based practice process

The evidence-based practice (EBP) process is a seven-step problem-solving approach that begins with data gathering (see Seven steps to EBP ). During daily practice, clinicians gather data supporting inquiry into a particular clinical issue (Step 0). The description is then framed as an answerable question (Step 1) using the PICOT question format ( P opulation of interest; I ssue of interest or intervention; C omparison to the intervention; desired O utcome; and T ime for the outcome to be achieved). 1 Consistently using the PICOT format helps ensure that all elements of the clinical issue are covered. Next, clinicians conduct a systematic search to gather data answering the PICOT question (Step 2). Using the PICOT framework, clinicians can systematically search multiple databases to find available studies to help determine the best practice to achieve the desired outcome for their patients. When the systematic search is completed, the work of critical appraisal begins (Step 3). The known group of valid and reliable studies that answers the PICOT question is called the body of evidence and is the foundation for the best practice implementation (Step 4). Next, clinicians evaluate integration of best evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences and values to determine if the outcomes in the studies are realized in practice (Step 5). Because healthcare is a community of practice, it is important that experiences with evidence implementation be shared, whether the outcome is what was expected or not. This enables critical care nurses concerned with similar care issues to better understand what has been successful and what has not (Step 6).

Critical appraisal of evidence

The first phase of critical appraisal, rapid critical appraisal, begins with determining which studies will be kept in the body of evidence. All valid, reliable, and applicable studies on the topic should be included. This is accomplished using design-specific checklists with key markers of good research. When clinicians determine a study is one they want to keep (a “keeper” study) and that it belongs in the body of evidence, they move on to phase 2, evaluation. 2

In the evaluation phase, the keeper studies are put together in a table so that they can be compared as a body of evidence, rather than individual studies. This phase of critical appraisal helps clinicians identify what is already known about a clinical issue. In the third phase, synthesis, certain data that provide a snapshot of a particular aspect of the clinical issue are pulled out of the evaluation table to showcase what is known. These snapshots of information underpin clinicians' decision-making and lead to phase 4, recommendation. A recommendation is a specific statement based on the body of evidence indicating what should be done—best practice. Critical appraisal is not complete without a specific recommendation. Each of the phases is explained in more detail below.

Phase 1: Rapid critical appraisal . Rapid critical appraisal involves using two tools that help clinicians determine if a research study is worthy of keeping in the body of evidence. The first tool, General Appraisal Overview for All Studies (GAO), covers the basics of all research studies (see Elements of the General Appraisal Overview for All Studies ). Sometimes, clinicians find gaps in knowledge about certain elements of research studies (for example, sampling or statistics) and need to review some content. Conducting an internet search for resources that explain how to read a research paper, such as an instructional video or step-by-step guide, can be helpful. Finding basic definitions of research methods often helps resolve identified gaps.

To accomplish the GAO, it is best to begin with finding out why the study was conducted and how it answers the PICOT question (for example, does it provide information critical care nurses want to know from the literature). If the study purpose helps answer the PICOT question, then the type of study design is evaluated. The study design is compared with the hierarchy of evidence for the type of PICOT question. The higher the design falls within the hierarchy or levels of evidence, the more confidence nurses can have in its finding, if the study was conducted well. 3,4 Next, find out what the researchers wanted to learn from their study. These are called the research questions or hypotheses. Research questions are just what they imply; insufficient information from theories or the literature are available to guide an educated guess, so a question is asked. Hypotheses are reasonable expectations guided by understanding from theory and other research that predicts what will be found when the research is conducted. The research questions or hypotheses provide the purpose of the study.

Next, the sample size is evaluated. Expectations of sample size are present for every study design. As an example, consider as a rule that quantitative study designs operate best when there is a sample size large enough to establish that relationships do not exist by chance. In general, the more participants in a study, the more confidence in the findings. Qualitative designs operate best with fewer people in the sample because these designs represent a deeper dive into the understanding or experience of each person in the study. 5 It is always important to describe the sample, as clinicians need to know if the study sample resembles their patients. It is equally important to identify the major variables in the study and how they are defined because this helps clinicians best understand what the study is about.

The final step in the GAO is to consider the analyses that answer the study research questions or confirm the study hypothesis. This is another opportunity for clinicians to learn, as learning about statistics in healthcare education has traditionally focused on conducting statistical tests as opposed to interpreting statistical tests. Understanding what the statistics indicate about the study findings is an imperative of critical appraisal of quantitative evidence.

The second tool is one of the variety of rapid critical appraisal checklists that speak to validity, reliability, and applicability of specific study designs, which are available at varying locations (see Critical appraisal resources ). When choosing a checklist to implement with a group of critical care nurses, it is important to verify that the checklist is complete and simple to use. Be sure to check that the checklist has answers to three key questions. The first question is: Are the results of the study valid? Related subquestions should help nurses discern if certain markers of good research design are present within the study. For example, identifying that study participants were randomly assigned to study groups is an essential marker of good research for a randomized controlled trial. Checking these essential markers helps clinicians quickly review a study to check off these important requirements. Clinical judgment is required when the study lacks any of the identified quality markers. Clinicians must discern whether the absence of any of the essential markers negates the usefulness of the study findings. 6-9

The second question is: What are the study results? This is answered by reviewing whether the study found what it was expecting to and if those findings were meaningful to clinical practice. Basic knowledge of how to interpret statistics is important for understanding quantitative studies, and basic knowledge of qualitative analysis greatly facilitates understanding those results. 6-9

The third question is: Are the results applicable to my patients? Answering this question involves consideration of the feasibility of implementing the study findings into the clinicians' environment as well as any contraindication within the clinicians' patient populations. Consider issues such as organizational politics, financial feasibility, and patient preferences. 6-9

When these questions have been answered, clinicians must decide about whether to keep the particular study in the body of evidence. Once the final group of keeper studies is identified, clinicians are ready to move into the phase of critical appraisal. 6-9

Phase 2: Evaluation . The goal of evaluation is to determine how studies within the body of evidence agree or disagree by identifying common patterns of information across studies. For example, an evaluator may compare whether the same intervention is used or if the outcomes are measured in the same way across all studies. A useful tool to help clinicians accomplish this is an evaluation table. This table serves two purposes: first, it enables clinicians to extract data from the studies and place the information in one table for easy comparison with other studies; and second, it eliminates the need for further searching through piles of periodicals for the information. (See Bonus Content: Evaluation table headings .) Although the information for each of the columns may not be what clinicians consider as part of their daily work, the information is important for them to understand about the body of evidence so that they can explain the patterns of agreement or disagreement they identify across studies. Further, the in-depth understanding of the body of evidence from the evaluation table helps with discussing the relevant clinical issue to facilitate best practice. Their discussion comes from a place of knowledge and experience, which affords the most confidence. The patterns and in-depth understanding are what lead to the synthesis phase of critical appraisal.

The key to a successful evaluation table is simplicity. Entering data into the table in a simple, consistent manner offers more opportunity for comparing studies. 6-9 For example, using abbreviations versus complete sentences in all columns except the final one allows for ease of comparison. An example might be the dependent variable of depression defined as “feelings of severe despondency and dejection” in one study and as “feeling sad and lonely” in another study. 10 Because these are two different definitions, they need to be different dependent variables. Clinicians must use their clinical judgment to discern that these different dependent variables require different names and abbreviations and how these further their comparison across studies.

Sample and theoretical or conceptual underpinnings are important to understanding how studies compare. Similar samples and settings across studies increase agreement. Several studies with the same conceptual framework increase the likelihood of common independent variables and dependent variables. The findings of a study are dependent on the analyses conducted. That is why an analysis column is dedicated to recording the kind of analysis used (for example, the name of the statistical analyses for quantitative studies). Only statistics that help answer the clinical question belong in this column. The findings column must have a result for each of the analyses listed; however, in the actual results, not in words. For example, a clinician lists a t -test as a statistic in the analysis column, so a t -value should reflect whether the groups are different as well as probability ( P -value or confidence interval) that reflects statistical significance. The explanation for these results would go in the last column that describes worth of the research to practice. This column is much more flexible and contains other information such as the level of evidence, the studies' strengths and limitations, any caveats about the methodology, or other aspects of the study that would be helpful to its use in practice. The final piece of information in this column is a recommendation for how this study would be used in practice. Each of the studies in the body of evidence that addresses the clinical question is placed in one evaluation table to facilitate the ease of comparing across the studies. This comparison sets the stage for synthesis.

Phase 3: Synthesis . In the synthesis phase, clinicians pull out key information from the evaluation table to produce a snapshot of the body of evidence. A table also is used here to feature what is known and help all those viewing the synthesis table to come to the same conclusion. A hypothetical example table included here demonstrates that a music therapy intervention is effective in reducing the outcome of oxygen saturation (SaO 2 ) in six of the eight studies in the body of evidence that evaluated that outcome (see Sample synthesis table: Impact on outcomes ). Simply using arrows to indicate effect offers readers a collective view of the agreement across studies that prompts action. Action may be to change practice, affirm current practice, or conduct research to strengthen the body of evidence by collaborating with nurse scientists.

When synthesizing evidence, there are at least two recommended synthesis tables, including the level-of-evidence table and the impact-on-outcomes table for quantitative questions, such as therapy or relevant themes table for “meaning” questions about human experience. (See Bonus Content: Level of evidence for intervention studies: Synthesis of type .) The sample synthesis table also demonstrates that a final column labeled synthesis indicates agreement across the studies. Of the three outcomes, the most reliable for clinicians to see with music therapy is SaO 2 , with positive results in six out of eight studies. The second most reliable outcome would be reducing increased respiratory rate (RR). Parental engagement has the least support as a reliable outcome, with only two of five studies showing positive results. Synthesis tables make the recommendation clear to all those who are involved in caring for that patient population. Although the two synthesis tables mentioned are a great start, the evidence may require more synthesis tables to adequately explain what is known. These tables are the foundation that supports clinically meaningful recommendations.

Phase 4: Recommendation . Recommendations are definitive statements based on what is known from the body of evidence. For example, with an intervention question, clinicians should be able to discern from the evidence if they will reliably get the desired outcome when they deliver the intervention as it was in the studies. In the sample synthesis table, the recommendation would be to implement the music therapy intervention across all settings with the population, and measure SaO 2 and RR, with the expectation that both would be optimally improved with the intervention. When the synthesis demonstrates that studies consistently verify an outcome occurs as a result of an intervention, however that intervention is not currently practiced, care is not best practice. Therefore, a firm recommendation to deliver the intervention and measure the appropriate outcomes must be made, which concludes critical appraisal of the evidence.

A recommendation that is off limits is conducting more research, as this is not the focus of clinicians' critical appraisal. In the case of insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for practice change, the recommendation would be to continue current practice and monitor outcomes and processes until there are more reliable studies to be added to the body of evidence. Researchers who use the critical appraisal process may indeed identify gaps in knowledge, research methods, or analyses, for example, that they then recommend studies that would fill in the identified gaps. In this way, clinicians and nurse scientists work together to build relevant, efficient bodies of evidence that guide clinical practice.

Evidence into action

Critical appraisal helps clinicians understand the literature so they can implement it. Critical care nurses have a professional and ethical responsibility to make sure their care is based on a solid foundation of available evidence that is carefully appraised using the phases outlined here. Critical appraisal allows for decision-making based on evidence that demonstrates reliable outcomes. Any other approach to the literature is likely haphazard and may lead to misguided care and unreliable outcomes. 11 Evidence translated into practice should have the desired outcomes and their measurement defined from the body of evidence. It is also imperative that all critical care nurses carefully monitor care delivery outcomes to establish that best outcomes are sustained. With the EBP paradigm as the basis for decision-making and the EBP process as the basis for addressing clinical issues, critical care nurses can improve patient, provider, and system outcomes by providing best care.

Seven steps to EBP

Step 0–A spirit of inquiry to notice internal data that indicate an opportunity for positive change.

Step 1– Ask a clinical question using the PICOT question format.

Step 2–Conduct a systematic search to find out what is already known about a clinical issue.

Step 3–Conduct a critical appraisal (rapid critical appraisal, evaluation, synthesis, and recommendation).

Step 4–Implement best practices by blending external evidence with clinician expertise and patient preferences and values.

Step 5–Evaluate evidence implementation to see if study outcomes happened in practice and if the implementation went well.

Step 6–Share project results, good or bad, with others in healthcare.

Adapted from: Steps of the evidence-based practice (EBP) process leading to high-quality healthcare and best patient outcomes. © Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2017. Used with permission.

Critical appraisal resources

- The Joanna Briggs Institute http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists

- Center for Evidence-Based Medicine www.cebm.net/critical-appraisal

- Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice . 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

A full set of critical appraisal checklists are available in the appendices.

Bonus content!

This article includes supplementary online-exclusive material. Visit the online version of this article at www.nursingcriticalcare.com to access this content.

critical appraisal; decision-making; evaluation of research; evidence-based practice; synthesis

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Determining the level of evidence: experimental research appraisal, nurse-driven protocols, evidence-based practice for red blood cell transfusions, recognizing and preventing drug diversion, pulmonary embolism: prevention, recognition, and treatment.

- Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Systematic Reviews

- Critical Appraisal by Study Design

Systematic Reviews: Critical Appraisal by Study Design

- Knowledge Synthesis Comparison

- Knowledge Synthesis Decision Tree

- Standards & Reporting Results

- Materials in the Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Training Resources

- Review Teams

- Develop & Refine Your Research Question

- Develop a Timeline

- Project Management

- Communication

- PRISMA-P Checklist

- Eligibility Criteria

- Register your Protocol

- Other Resources

- Other Screening Tools

- Grey Literature Searching

- Citation Searching

- Data Extraction Tools

- Minimize Bias

- Synthesis & Meta-Analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Tools for Critical Appraisal of Studies

“The purpose of critical appraisal is to determine the scientific merit of a research report and its applicability to clinical decision making.” 1 Conducting a critical appraisal of a study is imperative to any well executed evidence review, but the process can be time consuming and difficult. 2 The critical appraisal process requires “a methodological approach coupled with the right tools and skills to match these methods is essential for finding meaningful results.” 3 In short, it is a method of differentiating good research from bad research.

Critical Appraisal by Study Design (featured tools)

- Non-RCTs or Observational Studies

- Diagnostic Accuracy

- Animal Studies

- Qualitative Research

- Tool Repository

- AMSTAR 2 The original AMSTAR was developed to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews that included only randomized controlled trials. AMSTAR 2 was published in 2017 and allows researchers to “identify high quality systematic reviews, including those based on non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions.” 4 more... less... AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews)

- ROBIS ROBIS is a tool designed specifically to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews. “The tool is completed in three phases: (1) assess relevance(optional), (2) identify concerns with the review process, and (3) judge risk of bias in the review. Signaling questions are included to help assess specific concerns about potential biases with the review.” 5 more... less... ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews)

- BMJ Framework for Assessing Systematic Reviews This framework provides a checklist that is used to evaluate the quality of a systematic review.

- CASP Checklist for Systematic Reviews This CASP checklist is not a scoring system, but rather a method of appraising systematic reviews by considering: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What are the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools, Checklist for Systematic Reviews JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- RoB 2 RoB 2 “provides a framework for assessing the risk of bias in a single estimate of an intervention effect reported from a randomized trial,” rather than the entire trial. 6 more... less... RoB 2 (revised tool to assess Risk of Bias in randomized trials)

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trials Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of an RCT that require critical appraisal: 1. Is the basic study design valid for a randomized controlled trial? 2. Was the study methodologically sound? 3. What are the results? 4. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CONSORT Statement The CONSORT checklist includes 25 items to determine the quality of randomized controlled trials. “Critical appraisal of the quality of clinical trials is possible only if the design, conduct, and analysis of RCTs are thoroughly and accurately described in the report.” 7 more... less... CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- ROBINS-I ROBINS-I is a “tool for evaluating risk of bias in estimates of the comparative effectiveness… of interventions from studies that did not use randomization to allocate units… to comparison groups.” 8 more... less... ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias in Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions)

- NOS This tool is used primarily to evaluate and appraise case-control or cohort studies. more... less... NOS (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale)

- AXIS Cross-sectional studies are frequently used as an evidence base for diagnostic testing, risk factors for disease, and prevalence studies. “The AXIS tool focuses mainly on the presented [study] methods and results.” 9 more... less... AXIS (Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools for Non-Randomized Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. • Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies • Quality Assessment of Case-Control Studies • Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies With No Control Group • Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- Case Series Studies Quality Appraisal Checklist Developed by the Institute of Health Economics (Canada), the checklist is comprised of 20 questions to assess “the robustness of the evidence of uncontrolled, [case series] studies.” 10

- Methodological Quality and Synthesis of Case Series and Case Reports In this paper, Dr. Murad and colleagues “present a framework for appraisal, synthesis and application of evidence derived from case reports and case series.” 11

- MINORS The MINORS instrument contains 12 items and was developed for evaluating the quality of observational or non-randomized studies. 12 This tool may be of particular interest to researchers who would like to critically appraise surgical studies. more... less... MINORS (Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools for Non-Randomized Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. • Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies • Checklist for Case Control Studies • Checklist for Case Reports • Checklist for Case Series • Checklist for Cohort Studies

- QUADAS-2 The QUADAS-2 tool “is designed to assess the quality of primary diagnostic accuracy studies… [it] consists of 4 key domains that discuss patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow of patients through the study and timing of the index tests and reference standard.” 13 more... less... QUADAS-2 (a revised tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- STARD 2015 The authors of the standards note that “[e]ssential elements of [diagnostic accuracy] study methods are often poorly described and sometimes completely omitted, making both critical appraisal and replication difficult, if not impossible.”10 The Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies was developed “to help… improve completeness and transparency in reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies.” 14 more... less... STARD 2015 (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- CASP Diagnostic Study Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of diagnostic test studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Diagnostic Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- SYRCLE’s RoB “[I]mplementation of [SYRCLE’s RoB tool] will facilitate and improve critical appraisal of evidence from animal studies. This may… enhance the efficiency of translating animal research into clinical practice and increase awareness of the necessity of improving the methodological quality of animal studies.” 15 more... less... SYRCLE’s RoB (SYstematic Review Center for Laboratory animal Experimentation’s Risk of Bias)

- ARRIVE 2.0 “The [ARRIVE 2.0] guidelines are a checklist of information to include in a manuscript to ensure that publications [on in vivo animal studies] contain enough information to add to the knowledge base.” 16 more... less... ARRIVE 2.0 (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments)

- Critical Appraisal of Studies Using Laboratory Animal Models This article provides “an approach to critically appraising papers based on the results of laboratory animal experiments,” and discusses various “bias domains” in the literature that critical appraisal can identify. 17

- CEBM Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of qualitative research studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Tool Repository Created by librarians at Duke University, this extensive listing contains over 100 commonly used risk of bias tools that may be sorted by study type.

- Latitudes Network A library of risk of bias tools for use in evidence syntheses that provides selection help and training videos.

References & Recommended Reading

1. Kolaski, K., Logan, L. R., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2024). Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews . British Journal of Pharmacology , 181 (1), 180-210

2. Portney LG. Foundations of clinical research : applications to evidence-based practice. Fourth edition. ed. Philadelphia: F A Davis; 2020.

3. Fowkes FG, Fulton PM. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1991;302(6785):1136-1140.

4. Singh S. Critical appraisal skills programme. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. 2013;4(1):76-77.

5. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;358:j4008.

6. Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JPT, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:225-234.

7. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2019;366:l4898.

8. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010;63(8):e1-37.

9. Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;355:i4919.

10. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ open. 2016;6(12):e011458.

11. Guo B, Moga C, Harstall C, Schopflocher D. A principal component analysis is conducted for a case series quality appraisal checklist. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:199-207.e192.

12. Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ evidence-based medicine. 2018;23(2):60-63.

13. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ journal of surgery. 2003;73(9):712-716.

14. Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;155(8):529-536.

15. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;351:h5527.

16. Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RBM, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC medical research methodology. 2014;14:43.

17. Percie du Sert N, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS biology. 2020;18(7):e3000411.

18. O'Connor AM, Sargeant JM. Critical appraisal of studies using laboratory animal models. ILAR journal. 2014;55(3):405-417.

- << Previous: Minimize Bias

- Next: GRADE >>

- Last Updated: Jul 8, 2024 12:54 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.mayo.edu/systematicreviewprocess

Please enter both an email address and a password.

Account login

- Show/Hide Password Show password Hide password

- Reset Password

Need to reset your password? Enter the email address which you used to register on this site (or your membership/contact number) and we'll email you a link to reset it. You must complete the process within 2hrs of receiving the link.

We've sent you an email.

An email has been sent to Simply follow the link provided in the email to reset your password. If you can't find the email please check your junk or spam folder and add [email protected] to your address book.

- About RCS England

- Dissecting the literature: the importance of critical appraisal

08 Dec 2017

Kirsty Morrison

This post was updated in 2023.

Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value and relevance in a particular context.

Amanda Burls, What is Critical Appraisal?

Why is critical appraisal needed?

Literature searches using databases like Medline or EMBASE often result in an overwhelming volume of results which can vary in quality. Similarly, those who browse medical literature for the purposes of CPD or in response to a clinical query will know that there are vast amounts of content available. Critical appraisal helps to reduce the burden and allow you to focus on articles that are relevant to the research question, and that can reliably support or refute its claims with high-quality evidence, or identify high-level research relevant to your practice.

Critical appraisal allows us to:

- reduce information overload by eliminating irrelevant or weak studies

- identify the most relevant papers

- distinguish evidence from opinion, assumptions, misreporting, and belief

- assess the validity of the study

- assess the usefulness and clinical applicability of the study

- recognise any potential for bias.

Critical appraisal helps to separate what is significant from what is not. One way we use critical appraisal in the Library is to prioritise the most clinically relevant content for our Current Awareness Updates .

How to critically appraise a paper

There are some general rules to help you, including a range of checklists highlighted at the end of this blog. Some key questions to consider when critically appraising a paper:

- Is the study question relevant to my field?

- Does the study add anything new to the evidence in my field?

- What type of research question is being asked? A well-developed research question usually identifies three components: the group or population of patients, the studied parameter (e.g. a therapy or clinical intervention) and outcomes of interest.

- Was the study design appropriate for the research question? You can learn more about different study types and the hierarchy of evidence here .

- Did the methodology address important potential sources of bias? Bias can be attributed to chance (e.g. random error) or to the study methods (systematic bias).

- Was the study performed according to the original protocol? Deviations from the planned protocol can affect the validity or relevance of a study, e.g. a decrease in the studied population over the course of a randomised controlled trial .

- Does the study test a stated hypothesis? Is there a clear statement of what the investigators expect the study to find which can be tested, and confirmed or refuted.

- Were the statistical analyses performed correctly? The approach to dealing with missing data, and the statistical techniques that have been applied should be specified. Original data should be presented clearly so that readers can check the statistical accuracy of the paper.

- Do the data justify the conclusions? Watch out for definite conclusions based on statistically insignificant results, generalised findings from a small sample size, and statistically significant associations being misinterpreted to imply a cause and effect.

- Are there any conflicts of interest? Who has funded the study and can we trust their objectivity? Do the authors have any potential conflicts of interest, and have these been declared?

And an important consideration for surgeons:

- Will the results help me manage my patients?

At the end of the appraisal process you should have a better appreciation of how strong the evidence is, and ultimately whether or not you should apply it to your patients.

Further resources:

- How to Read a Paper by Trisha Greenhalgh

- The Doctor’s Guide to Critical Appraisal by Narinder Kaur Gosall

- CASP checklists

- CEBM Critical Appraisal Tools

- Critical Appraisal: a checklist

- Critical Appraisal of a Journal Article (PDF)

- Introduction to...Critical appraisal of literature

- Reporting guidelines for the main study types

Kirsty Morrison, Information Specialist

Share this page:

- Library Blog

Literature review methods

Critical appraisal, assess for quality.

Critical appraisal refers to the process of judging the validity and quality of a research paper. Because your review will be a synthesis of the research conducted by others, it is important to consider major points about the studies you include such as:

- Is the study valid?

- What are the results, and are they significant or trustworthy?

- Are the results applicable to your research question?

Critical appraisal tools

Several checklists or tools are available to help you assess the quality of studies to be included in your review.

- AACODS checklist for appraising grey literature

- CASP includes checklists for systematic reviews, RCTs, qualitative studies etc.

- Centre for Evidence Based Medicine appraisal worksheets to appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence

- Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools to assess the trustworthiness, relevance and results of published papers

- RoBiS tool for assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews (rather than in primary studies)

- RoB 2 Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials

Additional resources

- Greenhalgh, T. (2019). How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine and healthcare (6th ed). Wiley.

- << Previous: Screening

- Next: Synthesis analysis >>

Contact the library

- Ask the library

- Book time for search help

- Suggest an acquisition

- 036-10 10 10

- Follow us on Instagram

- Follow us on Facebook

Visiting address

University library Jönköping University campus, building C Gjuterigatan 5 553 18 Jönköping

- Delivery addresses

Opening hours

- Mondays 8 – 20

- Tuesdays 8 – 20

- Wednesdays 8 – 20

- Thursdays 8 – 20

- Fridays 8 – 18

- Saturdays 11 – 15

- Sundays Closed

See more opening hours .

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Specialty Certificate Examination Cases

- Cover Archive

- Virtual Issues

- Trending Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Reviewer Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Reasons to Publish

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Clinical and Experimental Dermatology

- About British Association of Dermatologists

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Discussion and conclusions, learning points, funding sources, data availability, ethics statement, cpd questions, instructions for answering questions.

- < Previous

How to critically appraise a systematic review: an aide for the reader and reviewer

Conflicts of interest H.W. founded the Cochrane Skin Group in 1987 and was coordinator editor until 2018. The other authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

John Frewen, Marianne de Brito, Anjali Pathak, Richard Barlow, Hywel C Williams, How to critically appraise a systematic review: an aide for the reader and reviewer, Clinical and Experimental Dermatology , Volume 48, Issue 8, August 2023, Pages 854–859, https://doi.org/10.1093/ced/llad141

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The number of published systematic reviews has soared rapidly in recent years. Sadly, the quality of most systematic reviews in dermatology is substandard. With the continued increase in exposure to systematic reviews, and their potential to influence clinical practice, we sought to describe a sequence of useful tips for the busy clinician reader to determine study quality and clinical utility. Important factors to consider when assessing systematic reviews include: determining the motivation to performing the study, establishing if the study protocol was prepublished, assessing quality of reporting using the PRISMA checklist, assessing study quality using the AMSTAR 2 critical appraisal checklist, assessing for evidence of spin, and summarizing the main strengths and limitations of the study to determine if it could change clinical practice. Having a set of heuristics to consider when reading systematic reviews serves to save time, enabling assessment of quality in a structured way, and come to a prompt conclusion of the merits of a review article in order to inform the care of dermatology patients.

A systematic review aims to systematically and transparently summarize the available data on a defined clinical question, via a rigorous search for studies, a critique of the quality of included studies and a qualitative and/or quantitative synthesis. 1 Systematic reviews are at the top of the pyramid in most evidence hierarchies for informing evidence-based healthcare as they are considered of greater validity and clinical applicability than those study types lower down, such as case series or individual trials. 2

A good systematic review should provide an unbiased overview of studies to inform clinical practice. Systematic reviews can reconcile apparently conflicting results, add precision to estimating smaller treatment effects, highlight the evidence’s limitations and biases and identify research gaps. Guidelines are available to assist systematic reviewers to transparently report why the review was done, the authors’ methods and findings via the PRISMA checklist. 3

The sharp rise in systematic review publications over time raises concern that the majority are unnecessary, misleading and/or conflicted. 4 A review of dermatology systematic reviews noted that 93% failed to report at least one PRISMA checklist item. 5 Another review of a random sample of 140/732 dermatology systematic reviews in 2017 found 90% were low quality. 6 Some improvements have occurred: reporting standards compliance has improved slightly (between 2013 and 2017), 5 and several leading dermatology journals including the British Journal of Dermatology have changed editorial policies, mandating authors to preregister review protocols.

Given the surge in poor-quality systematic review publications, we sought to describe a checklist of seven practical tips from the authors’ collective experience of writing and critically appraising systematic reviews, hoping that they will assist busy clinicians to critically appraise systematic reviews both as manuscript reviewers and as readers and research users.

Read the abstract to develop a sense of the subject.

What was the motivation for completing the review?

Has the review protocol been published and have changes been made to it.

Review the reporting quality .

Review the quality of the article and the depth of the review question.

Consider the authors’ interpretation and assess for spin .

Summarize and come to a position .

Read the abstract to develop a sense of the subject

From the abstract, use the PICO (population, intervention, comparator and outcome) framework to establish if the subject, intervention and outcomes are relevant to clinical practice. Is the review question clear and appropriate?

Inspect the authors’ conflicts of interest and funding sources. Self-disclosed financial conflicts are often insufficiently described or not declared at all. 7 If you suspect conflicts for authors with no stated conflicts, briefly searching the senior authors’ names on PubMed, or the Open Payments website (for US authors) may reveal hidden conflicts. 8 Is the motivation for the systematic review justified in the introduction? Can new insights be formed by combining studies? If the systematic review is an update, what new available data justifies this? Search for similar recent systematic reviews (which may have been omitted intentionally). Is it a redundant duplicate review that adds little new useful information? 9 Has the author recently published reviews on similar subjects? Salami publications refer to authors chopping up a topic into smaller pieces to obtain maximum publications. 10

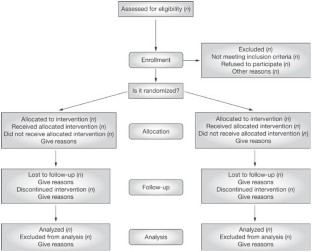

Search PROSPERO for publication of the review protocol. 11 A prepublished review protocol in a publicly accessible site offers reassurance that the systematic review followed a clear plan with prespecified PICO elements. Put bluntly, it reduces authors’ opportunity for deception by selective analysis and highlighting of results that are more likely to get published. If a protocol is found, assess deviation from this protocol and justification, if present. Protocol registration allows improved PRISMA reporting. 12 A registered protocol with reporting of deviations allows the reader to judge whether any modifications are justified, for example adjusting for unexpected challenges during analysis. 10

Review the reporting quality

Look for supplementary material detailing the PRISMA checklist. Commonly under-reported PRISMA items include protocol and registration, risk of bias across studies, risk of bias in individual studies, the data collection process and review objectives. 5 Adequate reporting quality using PRISMA does not necessarily indicate the review is clinically useful; however, it allows the reader to assess the study’s utility (see Table 1 ). Additional assessments of review quality are described below.

The relationship between systematic review reporting quality and study quality a

| Reporting quality . | Study quality . | |

|---|---|---|

| Good | Flawed | |