THE EFFECT OF INTERNET ADDICTION ON STUDENTS' EMOTIONAL AND ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE

- January 2017

- e-Academia Journal 6(1):86-98

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- Universiti Teknologi MARA

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Aina Masturina Azri

- Eryn Izrina Samsudin

- Imran Hussain

- Nor Sa'adah Zulkifli

- Muhammad Hanif Abd Latif

- J. Antonio Muhaji

- Evi Ulina Margareta Situmorang

- Laurentius Aswin Pramono

- Bryan Nathaniel

- Rusdi Ali Mustafa

- Hewa Abdulazeez Jameel

- Muhammad Irfannizamani

- Fariza Oskenbay

- Salima Nugmanova

- Claes Fornell

- David F. Larcker

- NEW MEDIA SOC

- Jannette A. Mena

- COMPUT HUM BEHAV

- Yufang Bian

- L R Goldberg

- Fatma Ozgun Ozturk

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

The impact of internet addiction on mental health: exploring the mediating effects of positive psychological capital in university students.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. benefits of psychological capital, 1.2. conceptual framework, internet addiction, psychological capital, and mental health, 1.3. gaps in the literature, 1.4. research questions and hypotheses.

- To what extent do the Amharic versions of the Internet Addiction Scale (IAS), the Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-24), and the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) exhibit high levels of reliability and validity?

- Is there a negative relationship between Internet Addiction (IA) and Psychological Capital (PsyCap) and Mental health (MH) among undergraduate young students?

- Does PsyCap positively predict MH among undergraduate young university students?

- Does PsyCap mediate the relationship between IA and MH among undergraduate young university students?

2.1. Research Design

2.2. sample and sampling, 2.3. instruments, 2.3.1. socio-demographic information, 2.3.2. internet addiction scale (ias), 2.3.3. psychological capital questionnaire (pcq-24), 2.3.4. mental health continuum-short form [mhc-sf], 2.4. statistical data analysis, 2.5. procedures of the studies, 2.5.1. adaption, translation, and validation of the measures, 2.5.2. ethics of this study, 3.1. results of preliminary analysis, 3.1.1. descriptive statistics, skewness, and kurtosis, 3.1.2. multi-collinearity, 3.1.3. reliability and validity evidence of the main variables, 3.1.4. measurement and structural model.

| Models | Variables of this Study | Fitness of Indices Using Confirmatory Factorial Analysis of the Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ | TLI | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA | ||

| Model 1 | Internet Addiction (see ) | 364.80 (113) ** | 0.973 | 0.977 | 0.031 | 0.051 |

| Model 2 | PsyCap (see ) | 2005.74 (246) ** | 0.915 | 0.924 | 0.046 | 0.092 |

| Model 3 | Mental Health (see ) | 234.75 (74) ** | 0.986 | 0.989 | 0.016 | 0.051 |

| Model 4 | Measurement Model | 4384 (1375) ** | 0.935 | 0.940 | 0.037 | 0.051 |

| Structural Model | 4660 (1416) ** | 0.932 | 0.935 | 0.046 | 0.052 | |

| Rule of Thumb | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.08 | >1.00 | ||

Click here to enlarge figure

3.1.5. Mediation Testing Using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

4. discussion, 5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Leung, H.; Pakpour, A.H.; Strong, C.; Lin, Y.C.; Tsai, M.C.; Griffiths, M.D.; Lin, C.Y.; Chen, I.H. Measurement invariance across young adults from Hong Kong and Taiwan among three internet-related addiction scales: Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS), Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS), and Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form (IGDS-SF9) (Study Part A). Addict. Behav. 2020 , 101 , 105969. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Kuss, D.J.; Van Rooij, A.J.; Shorter, G.W.; Griffiths, M.D.; Van De Mheen, D. Internet addiction in adolescents: Prevalence and risk factors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013 , 29 , 1987–1996. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shao, X.; Ni, X. How Does Family Intimacy Predict Self-Esteem in Adolescents? Moderation of Social Media Use Based on Gender Difference. SAGE Open 2021 , 11 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kayiş, A.R.; Satici, S.A.; Yilmaz, M.F.; Şimşek, D.; Ceyhan, E.; Bakioğlu, F. Big five-personality trait and internet addiction: A meta-analytic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016 , 63 , 35–40. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zhao, X.; Han, S.; Wu, W. Unravelling the veil of appearance anxiety: Exploring social media use among Chinese young people. BMC Psychol. 2024 , 12 , 9. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Yang, S.C.; Tung, C. Comparison of Internet addicts and non-addicts in Taiwanese high school. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007 , 23 , 79–96. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Koc, M.; Gulyagci, S. Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: The role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013 , 16 , 279–284. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007 , 60 , 541–572. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bi, X.; Jin, J. Psychological Capital, College Adaptation, and Internet Addiction: An Analysis Based on Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2021 , 12 , 712964. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zewude, G.T.; Hercz, M. The Teacher Well-Being Scale (TWBS): Construct validity, model comparisons and measurement invariance in an Ethiopian setting. J. Psychol. Afr. 2022 , 32 , 251–262. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alonzo, R.; Hussain, J.; Stranges, S.; Anderson, K.K. Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021 , 56 , 101414. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Canan, F.; Ataoglu, A.; Nichols, L.A.; Yildirim, T.; Ozturk, O. Evaluation of Psychometric Properties of the Internet Addiction Scale in a Sample of Turkish. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010 , 13 , 4–7. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Prasetya, T.A.E.; Wardani, R.W.K. Systematic review of social media addiction among health workers during the pandemic COVID-19. Heliyon 2023 , 9 , e16784. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Arslan, G.; Coşkun, M. Social Exclusion, Self-Forgiveness, Mindfulness, and Internet Addiction in College Students: A Moderated Mediation Approach. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022 , 20 , 2165–2179. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Xu, S.; Wang, Z.; David, P. Social media multitasking (SMM) and well-being: Existing evidence and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022 , 47 , 101345. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Woods, H.C.; Scott, H. #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 2016 , 51 , 41–49. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Xue, B.; Wang, S.; Chen, D.; Hu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Luo, H. Moral distress, psychological capital, and burnout in registered nurses. Nurs. Ethics 2023 , 9697330231202233. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Boer, M.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Finkenauer, C.; de Looze, M.E.; van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M. Social media use intensity, social media use problems, and mental health among adolescents: Investigating directionality and mediating processes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021 , 116 , 106645. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ziapour, A.; Lebni, J.Y.; Toghroli, R.; Abbas, J.; NeJhaddadgar, N.; Salahshoor, M.R.; Mansourian, M.; Gilan, H.D.; Kianipour, N.; Chaboksavar, F.; et al. A study of internet addiction and its effects on mental health: A study based on Iranian University Students. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020 , 9 , 205. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hannah, S.T.; Avolio, B.J. Moral potency: Building the capacity for character-based leadership. Consult. Psychol. J. 2010 , 62 , 291–310. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jiang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zuo, C. Investigating links between Internet literacy, Internet use, and Internet addiction among Chinese youth and adolescents in the digital age. Front. Psychiatry 2023 , 14 , 1233303. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sondhi, N.; Joshi, H. Multidimensional Assessment of Internet Addiction: Scale Development and Validation. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2024 , 25 , 85–98. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alshakhsi, S.; Chemnad, K.; Almourad, M.B.; Altuwairiqi, M.; McAlaney, J.; Ali, R. Problematic internet usage: The impact of objectively Recorded and categorized usage time, emotional intelligence components and subjective happiness about usage. Heliyon 2022 , 8 , e11055. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bohlmeijer, E.; Westerhof, G. The Model for Sustainable Mental Health: Future Directions for Integrating Positive Psychology Into Mental Health Care. Front. Psychol. 2021 , 12 , 747999. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Keyes, C.L.M. The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002 , 43 , 207–222. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Pei, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, H. Network connectivity between anxiety, depressive symptoms and psychological capital in Chinese university students during the COVID-19 campus closure. J. Affect. Disord. 2023 , 329 , 11–18. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zewude, G.T.; Hercz, M. Does Work Task Motivation Mediate the Relationship Between Psychological Capital and Teacher Well-being? Psihologija 2024 , 57 , 129–153. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zheng, Q.; Liu, S.; Zheng, J.; Gu, M.; He, W. College students’ loneliness and problematic mobile phone use: Mediation by fear of missing out. J. Psychol. Afr. 2023 , 33 , 115–121. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Preston, A.; Rew, L.; Young, C.C. A Systematic Scoping Review of Psychological Capital Related to Mental Health in Youth. J. Sch. Nurs. 2023 , 39 , 72–86. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Davis, R.A. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2001 , 17 , 187–195. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004 , 359 , 1367–1377. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Flaherty, J.A. Developing instruments for cross cultural research. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1988 , 176 , 257–263. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Essel, H.B.; Vlachopoulos, D.; Nyadu-Addo, R.; Tachie-Menson, A.; Baah, P.K.; Owusu-Antwi, C. The Impact of Mental Health Predictors of Internet Addiction among Pre-Service Teachers in Ghana. Behav. Sci. 2023 , 13 , 20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Kuss, D.J.; Kristensen, A.M.; Lopez-Fernandez, O. Internet addictions outside of Europe: A systematic literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021 , 115 , 106621. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being ; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dutt, B. Social media wellbeing: Perceived wellbeing amidst social media use in Norway. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023 , 7 , 100436. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge ; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Echeverría, G.; Torres, M.; Pedrals, N.; Padilla, O.; Rigotti, A.; Bitran, M. Validation of a Spanish Version of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form Questionnaire. Psicothema 2017 , 29 , 96–102. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Strang, K.D. The Palgrave Handbook of Research Design in Business and Management ; Springer Science and Business Media LLC.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dirzyte, A.; Perminas, A.; Biliuniene, E. Psychometric properties of satisfaction with life scale (Swls) and psychological capital questionnaire (pcq-24) in the lithuanian population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021 , 18 , 2608. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Görgens-Ekermans, G.; Herbert, M. Psychological capital: Internal and external validity of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-24) on a South African sample. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2013 , 39 , 1–12. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Choisay, F.; Fouquereau, E.; Coillot, H.; Chevalier, S. Validation of the French Psychological Capital Questionnaire (F-PCQ-24) and its measurement invariance using bifactor exploratory structural equation modeling framework. Mil. Psychol. 2021 , 33 , 50–65. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cid, D.T.; do Carmo Fernandes Martins, M.; Dias, M.; Fidelis, A.C.F. Psychological capital questionnaire (PCQ-24): Preliminary evidence of psychometric validity of the Brazilian version. Psico-USF 2020 , 25 , 63–74. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hedrih, V. Adapting Psychological Tests and Measurement Instruments for Cross-Cultural Research ; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine 2000 , 25 , 3186–3191. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Davidov, E.; Schmidt, P.; Billiet, J.; Meuleman, B. Cross-Cultural Analysis:Methods and Application , 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis , 8th ed.; Ainscow, A., Ed.; Cengage India: New Delhi, India, 2019. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling ; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2016; Volume 4. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zewude, G.T.; Mária, H.; Taye, B.; Demissew, S. COVID-19 Stress and Teachers Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Sense of Coherence and Resilience. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023 , 13 , 1–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference ; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; Volume 16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zewude, G.T.; Hercz, M. Psychometric Properties and Measurement Invariance of the PERMA Profiler in an Ethiopian Higher Education Setting. Pedagogika 2022 , 146 , 209–236. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013 , 38 , 52–54. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.M.; Singh, U.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019 , 22 , 67–72. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999 , 6 , 1–55. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951 , 16 , 297–334. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhang, C.; Li, G.; Fan, Z.; Tang, X.; Zhang, F. Psychological Capital Mediates the Relationship Between Problematic Smartphone Use and Learning Burnout in Chinese Medical Undergraduates and Postgraduates: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychol. 2021 , 12 , 600352. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Young, K.S. Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1998 , 1 , 237–244. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zewude, G.T.; Hercz, M. Psychological Capital and Teacher Well-being: The Mediation Role of Coping with Stress. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2021 , 10 , 1227–1245. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Turliuc, M.N.; Candel, O.S. The relationship between psychological capital and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal mediation model. J. Health Psychol. 2022 , 27 , 1913–1925. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

| Variables | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet craving | 5.000 | 25.000 | 20.032 | 4.87852 | −1.128 | 0.772 |

| Internet compulsive disorder | 4.000 | 20.000 | 14.719 | 4.201 | −0.745 | −0.202 |

| Addictive behavior | 4.000 | 20.000 | 15.528 | 3.870 | −0.962 | 0.368 |

| Internet obsession | 4.000 | 20.000 | 14.358 | 4.749 | −0.618 | −0.719 |

| Internet addiction | 17.000 | 85.000 | 64.636 | 13.720 | −1.080 | 1.580 |

| Hope | 6.000 | 36.000 | 23.696 | 7.663 | −0.831 | −0.040 |

| Efficacy | 6.000 | 36.000 | 21.701 | 8.300 | −0.282 | −0.770 |

| Resilience | 6.000 | 36.000 | 22.202 | 7.608 | −0.343 | −0.593 |

| Optimism | 6.000 | 36.000 | 21.423 | 7.749 | −0.385 | −0.720 |

| PsyCap | 24.000 | 144.000 | 89.023 | 25.91 | −0.489 | 0.288 |

| Emotional well-being | 3.00 | 21.00 | 11.615 | 4.105 | −0.786 | −0.494 |

| Psychological well-being | 6.00 | 42.00 | 25.115 | 7.719 | −1.080 | 0.249 |

| Social well-being | 5.00 | 35.00 | 21.139 | 6.472 | −0.489 | 0.241 |

| Mental health | 14.00 | 98.00 | 57.869 | 16.574 | −0.815 | 0.944 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| Internet addiction | −0.265 | −0.219 | −7.697 | 0.000 | 0.920 | 1.086 |

| PsyCap | 0.324 | 0.507 | 17.819 | 0.000 | 0.920 | 1.086 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | |||||||||||||||||

| −0.006 | - | ||||||||||||||||

| 0.096 ** | 00.020 | - | |||||||||||||||

| −0.068 * | −0.013 | −0.006 | - | ||||||||||||||

| −0.008 | −0.001 | −0.011 | 0.613 ** | - | |||||||||||||

| −0.047 | 0.021 | −0.012 | 0.540 ** | 0.436 ** | - | ||||||||||||

| −0.053 | 0.016 | 0.014 | 0.433 ** | 0.459 ** | 0.305 ** | - | |||||||||||

| −0.111 ** | −0.007 | −0.045 | −0.216 ** | −0.165 ** | −0.083 * | −0.162 ** | - | ||||||||||

| −0.018 | 0.024 | −0.026 | −0.271 ** | −0.133 ** | −0.222 ** | −0.135 ** | 0.750 ** | - | |||||||||

| −0.137 ** | 0.006 | 0.011 | −0.269 ** | −0.253 ** | −0.143 ** | −0.248 ** | o.598 ** | o.570 ** | - | ||||||||

| −0.033 | −0.014 | 0.058 | −0.226 ** | −0.163 ** | −0.225 ** | 0.028 | 0.515 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.506 ** | - | |||||||

| 0.044 | −0.011 | 0.034 | −0.258 ** | −0.242 ** | −0.190 ** | −0.282 ** | 0.458 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.272 ** | - | ||||||

| 0.054 | −0.028 | 0.041 | −0.274 ** | −0.262 ** | −0.179 ** | −0.298 ** | 0.479 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.453 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.673 ** | - | |||||

| 0.001 | 0.018 | 0.057 | −0.286 ** | −0.237 ** | −0.208 ** | −0.285 ** | 0.536 ** | 0.499 ** | 0.476 ** | 0.294 ** | 0.715 ** | 0.758 ** | - | ||||

| −0.058 | 0.007 | −0.004 | 0.845 ** | 0.806 ** | 0.713 ** | 0.727 ** | −0.207 ** | −0.247 ** | −0.299 ** | −0.184 ** | −0.317 ** | −0.331 ** | −0.332 ** | - | |||

| −0.069 | 0.003 | −0.001 | −0.296 ** | −0.214 ** | −0.204 ** | −0.155 ** | 0.863 ** | 0.874 ** | 0.802 ** | 0.778 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.507 ** | 0.544 ** | −0.282 ** | - | ||

| 0.036 | −0.016 | 0.050 | −0.303 ** | −0.275 ** | −0.212 ** | −0.320 ** | 0.546 ** | 0.520 ** | 0.503 ** | 0.319 ** | 0.840 ** | 0.928 ** | 0.920 ** | −0.362 ** | 0.569 ** | - |

| Internet Addicton Scale (IAS) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | α | CR | AVE (>0.50 *) | MSV | Squared correlation | |||

| (>0.70 *) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| 1. Internet Craving | 0.883 | 0.883 | 0.658 | 0.44 | - | |||

| 2. Internet Compulsive Disorder | 0.927 | 0.927 | 0.719 | 0.44 | 0.44 | - | ||

| 3. Addictive Behavior | 0.904 | 0.904 | 0.703 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.22 | - | |

| 4. Internet Obsession | 0.926 | 0.926 | 0.760 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.11 | - |

| Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-24) | ||||||||

| Models | α | CR | AVE (>0.50 *) | MSV | Squared correlation | |||

| (>0.70 *) | H | E | R | O | ||||

| Hope (H) | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.791 | 0.59 | - | |||

| Efficacy (E) | 0.950 | 0.951 | 0.764 | 0.59 | 0.59 ** | - | ||

| Resilience (R) | 0.946 | 0.947 | 0.745 | 0.38 | 0.38 ** | 0.34 ** | - | |

| Optimism (O) | 0.957 | 0.957 | 0.788 | 0.34 | 0.29 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.26 ** | - |

| Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) | ||||||||

| Models | α | CR | AVE (>0.50 *) | MSV | Squared correlation | |||

| EWB | PWB | SWB | ||||||

| Emotional Well-Being (EWB) | 0.934 | 0.934 | 0.825 | 0.62 | - | |||

| Psychological Well-Being (PWB) | 0.964 | 0.964 | 0.818 | 0.59 | 0.50 ** | - | ||

| Social Well-Being (SWB) | 0.959 | 0.960 | 0.826 | 0.62 | 0.62 ** | 0.57 ** | - | |

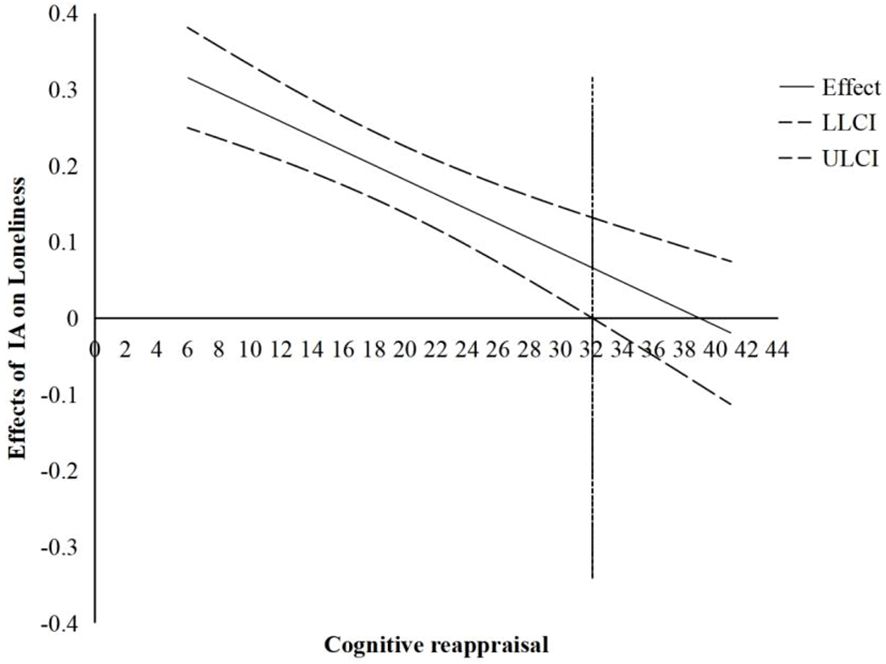

| Predictors | Outcome Variables | Bootstrap 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | LBC | UBC | p-Value | ||

| Standardized Direct Effect | |||||

| Internet addiction | PsyCap | −0.327 | −0.414 | −0.248 | 0.001 |

| Internet addiction | Mental Health | −0.211 | −0.277 | −0.140 | 0.003 |

| PsyCap | Mental Health | 0.595 | 0.533 | 0.658 | 0.001 |

| Standardized Indirect Effect | |||||

| Internet addiction → PsyCap → | Mental Health ( ) | −0.195 | −0.252 | −0.146 | 0.001 |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Zewude, G.T.; Bereded, D.G.; Abera, E.; Tegegne, G.; Goraw, S.; Segon, T. The Impact of Internet Addiction on Mental Health: Exploring the Mediating Effects of Positive Psychological Capital in University Students. Adolescents 2024 , 4 , 200-221. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents4020014

Zewude GT, Bereded DG, Abera E, Tegegne G, Goraw S, Segon T. The Impact of Internet Addiction on Mental Health: Exploring the Mediating Effects of Positive Psychological Capital in University Students. Adolescents . 2024; 4(2):200-221. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents4020014

Zewude, Girum Tareke, Derib Gosim Bereded, Endris Abera, Goche Tegegne, Solomon Goraw, and Tesfaye Segon. 2024. "The Impact of Internet Addiction on Mental Health: Exploring the Mediating Effects of Positive Psychological Capital in University Students" Adolescents 4, no. 2: 200-221. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents4020014

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

A study of internet addiction and its effects on mental health: A study based on Iranian University Students

Affiliations.

- 1 Health Education and Health Promotion, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

- 2 Social Determinants in Health Promotion Research Center, Hormozgan Health Institute, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, Iran.

- 3 Antai College of Economics and Management/School of Media and Communication, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai-China.

- 4 Department of Health Care Services and Health Education, School of Health, Ardabil University of Medical Science, Ardabil, Iran.

- 5 Department of Anatomical Sciences, Medical School, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

- 6 Health Management and Economics Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

- 7 Students Research Committee, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

- PMID: 33062738

- PMCID: PMC7530416

- DOI: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_148_20

Introduction: The Internet has drastically affected human behavior, and it has positive and negative effects; however, its excessive usage exposes users to internet addiction. The diagnosis of students' mental dysfunction is vital to monitor their academic progress and success by preventing this technology through proper handling of the usage addiction.

Materials and methods: This descriptive-analytical study selected 447 students (232 females and 215 males) of the first and second semesters enrolled at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Iran, in 2018 by using Cochrane's sample size formula and stratified random sampling. The study applied Young's Internet Addiction Test and Goldberg General Health Questionnaire 28 for data collection. The study screened the data received and analyzed valid data set through the t -test and Pearson's correlation coefficient by incorporating SPSS Statistics software version 23.0.

Results: The results of the current study specified that the total mean score of the students for internet addiction and mental health was 3.81 ± 0.88 and 2.56 ± 0.33, correspondingly. The results revealed that internet addiction positively correlated with depression and mental health, which indicated a negative relationship ( P > 0.001). The multiple regression analysis results showed students' five significant vulnerability predictors toward internet addiction, such as the critical reason for using the Internet, faculty, depression, the central place for using the Internet, and somatic symptoms.

Conclusions: The study findings specified that students' excessive internet usage leads to anxiety, depression, and adverse mental health, which affect their academic performance. Monitoring and controlling students' internet addiction through informative sessions on how to use the Internet adequately is useful.

Keywords: Internet addiction; medical sciences; mental health; students; technology advancement.

Copyright: © 2020 Journal of Education and Health Promotion.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Similar articles

- Internet Addiction Status and Related Factors among Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Western Iran. Khazaie H, Lebni JY, Abbas J, Mahaki B, Chaboksavar F, Kianipour N, Toghroli R, Ziapour A. Khazaie H, et al. Community Health Equity Res Policy. 2023 Jul;43(4):347-356. doi: 10.1177/0272684X211025438. Epub 2021 Jun 15. Community Health Equity Res Policy. 2023. PMID: 34128427

- Self-rated Health and Internet Addiction in Iranian Medical Sciences Students; Prevalence, Risk Factors and Complications. Mohammadbeigi A, Valizadeh F, Mirshojaee SR, Ahmadli R, Mokhtari M, Ghaderi E, Ahmadi A, Rezaei H, Ansari H. Mohammadbeigi A, et al. Int J Biomed Sci. 2016 Jun;12(2):65-70. Int J Biomed Sci. 2016. PMID: 27493592 Free PMC article.

- Internet addiction and its predictors in guilan medical sciences students, 2012. Asiri S, Fallahi F, Ghanbari A, Kazemnejad-Leili E. Asiri S, et al. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2013 Jun;2(2):234-9. doi: 10.5812/nms.11626. Epub 2013 Jun 27. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2013. PMID: 25414864 Free PMC article.

- Prevalence of Internet Addiction Among Iranian University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Salarvand S, N Albatineh A, Dalvand S, Baghban Karimi E, Ghanei Gheshlagh R. Salarvand S, et al. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2022 Apr;25(4):213-222. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2021.0120. Epub 2022 Jan 25. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2022. PMID: 35085012 Review.

- How Have Researchers Acknowledged and Controlled for Academic Work Activity When Measuring Medical Students' Internet Addiction? A Systematic Literature Review. Masters K, Loda T, Tervooren F, Herrmann-Werner A. Masters K, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jul 20;18(14):7681. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147681. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. PMID: 34300132 Free PMC article. Review.

- White matter integrity of right frontostriatal circuit predicts internet addiction severity among internet gamers. Zhou H, Gong L, Su C, Teng B, Xi W, Li X, Geng F, Hu Y. Zhou H, et al. Addict Biol. 2024 May;29(5):e13399. doi: 10.1111/adb.13399. Addict Biol. 2024. PMID: 38711213 Free PMC article.

- Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry. Abbas J, Mubeen R, Iorember PT, Raza S, Mamirkulova G. Abbas J, et al. Curr Res Behav Sci. 2021 Nov;2:100033. doi: 10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100033. Epub 2021 Apr 20. Curr Res Behav Sci. 2021. PMID: 38620720 Free PMC article.

- Explanation of the internet addiction model based on academic performance, academic experience, and clinical self-efficacy in nursing students: A path analysis. Khatony A, Azizi SM, Janatolmakan M, Jafari F, Mohammadi MM. Khatony A, et al. J Educ Health Promot. 2024 Jan 22;12:459. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_297_23. eCollection 2023. J Educ Health Promot. 2024. PMID: 38464625 Free PMC article.

- Prevalence of Internet Addiction and Its Associated Risk Factors Among Medical Students in Sudan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Mohamed KO, Soumit SM, Elseed AA, Allam WA, Soomit AM, Humeda HS. Mohamed KO, et al. Cureus. 2024 Feb 4;16(2):e53543. doi: 10.7759/cureus.53543. eCollection 2024 Feb. Cureus. 2024. PMID: 38445147 Free PMC article.

- Formulation of precise exercise intervention strategy for adolescent depression. Chen X, Zeng X, Liu C, Lu P, Shen Z, Yin R. Chen X, et al. Psych J. 2024 Apr;13(2):176-189. doi: 10.1002/pchj.726. Epub 2024 Feb 1. Psych J. 2024. PMID: 38298170 Free PMC article. Review.

- Bisen SS, Deshpande YM. Prevalence, predictors, psychological correlates of internet addiction among college students in India: A comprehensive study. Anatol J Psychiatry. 2020;21:117–23.

- Abbas J, Aman J, Nurunnabi M, Bano S. The impact of social media on learning behavior for sustainable education: Evidence of students from selected universities in Pakistan. Sustainabil. 2019;11:1683–91.

- Zhang MW, Lim RB, Lee C, Ho RC. Prevalence of internet addiction in medical students: A meta-analysis. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42:88–93. - PubMed

- Reshadat S, Zangeneh A, Saeidi S, Ghasemi SR, Rajabi Gilan N, Abbasi S. Investigating the economic, social and cultural factors influencing total fertility rate in Kermanshah. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2015;25:108–12.

- Bener A, Yildirim E, Torun P, Çatan F, Bolat E, Alıç S, et al. Internet addiction, fatigue, and sleep problems among adolescent students: A large-scale study. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2018;24:1–11.

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- PubMed Central

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

- Submit a Manuscript

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Study of internet addiction and its association with depression and insomnia in university students

Jain, Akhilesh 1 ; Sharma, Rekha 2 ; Gaur, Kusum Lata 3 ; Yadav, Neelam 4 ; Sharma, Poonam 5 ; Sharma, Nikita 5 ; Khan, Nazish 5 ; Kumawat, Priyanka 5 ; Jain, Garima 4 ; Maanju, Mukesh 1 ; Sinha, Kartik Mohan 6 ; Yadav, Kuldeep S. 1,

1 Department of Psychiatry, ESIC Model Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

2 Department of Ophthalmology, ESIC Model Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

3 Department of PSM, SMS Medical College, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

4 Department of Medicine, ESIC Model Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

5 Department of Psychology, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

6 Manipal University, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

Address for correspondence: Dr. Kuldeep S. Yadav, Senior Resident, Department of Psychiatry, ESIC Model Hospital, 3-D/162, Chitrakoot, Ajmer Road, Jaipur - 302 021, Rajasthan, India. E-mail: [email protected]

Received December 18, 2019

Received in revised form January 31, 2020

Accepted February 12, 2020

Introduction:

Use of internet has increased exponentially worldwide with prevalence of internet addiction ranging from 1.6% to 18 % or even higher. Depression and insomnia has been linked with internet addiction and overuse in several studies.

Aims and Objectives:

Present study has looked in to pattern and prevalence of internet addiction in university students. This study has also explored the association of internet addiction with depression and insomnia.

Material and Methods:

In this cross sectional study 954 subjects were enrolled who had been using internet for past 6 months. Information regarding pattern of use and socio demographic characteristics were recorded. Internet addiction Test (IAT), PHQ-9,and insomnia Severity Index (ISI) were applied to measure internet addiction, depression and insomnia respectively.

Results:

Among 954 subjects, 518 (60.59%) were male and 376 (39.41%) were female with mean age of 23.81 (SD ± 3.72). 15.51% study subjects were internet addicts and 49.19% were over users. Several parameters including graduation level, time spent per day on line, place of internet use, smoking and alcohol had significant association with internet addiction. Internet addiction was predominantly associated with depression and insomnia.

Conclusion:

Internet addiction is a rising concern among youth. Several parameters including gender, time spent on line, alcohol, smoking predicts higher risk of internet addiction. Depression and insomnia are more common in internet addicts and overusers.

Introduction

Exponential growth in internet use has been observed across the world including India in the last decade. About 205 million internet users were reported in India in 2012 including both rural and urban population and it was predicted that India will become the second leading country after China in internet usage.[ 1 ] Internet is used for various reasons such as interpersonal communication, exploring information, business transactions, and entertainment. However, it can also provide an opportunity to engage in excessive chatting, pornography, gaming, or even gambling. There have been growing concerns worldwide for what has been labeled as “internet addiction.”

Dr. Ivan Goldberg suggested the term “internet addiction” in 1995 for pathological compulsive internet use.[ 2 ] Excessive internet use was closely linked to pathological gambling by Young[ 3 ] who adapted the DSM IV criteria to relate to internet use in the internet addiction test (IAT) developed by her. The prevalence of internet addiction has been reported ranging from 1.6% to 18% in different populations.[ 4 5 ]

General population surveys show a prevalence of 0.3–0.7%.[ 6 ] with addicted spending average 38.5 h/week on a computer as compared to the nonaddicted averaged 4.9 h/week. Goel[ 7 ] has reported 24.8% as possible addicts, and 0.7% as addicts in his study of internet addiction among Indian adolescents.

Overuse of the internet has been linked with many psychological conditions including anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Several studies[ 8 9 ] have shown that among users addicted to the internet, depression has much prevalence than normal users. Akini and Iskender[ 10 ] have reported that depression and anxiety are significant predictors of internet addiction in a study among Turkish students.

There is an influence of problematic internet use or internet addiction on sleep patterns. Increased time spent on the internet may disrupt the sleep-wake schedule significantly, and a higher rate of sleep disturbance takes place among heavy internet users.[ 11 ] Wong[ 12 ] studied the impact of online addiction on insomnia and depression on Hong Kong adolescents. The findings showed that “internet addiction was associated significantly with insomnia and depression”. These data imply that possible complex mechanisms exist between insomnia, internet addiction, and depression.

Internet use has been overwhelmingly increasing in India, involving especially the youth population. Since adolescents contribute a significant proportion of the productive life age of our country, their involvement with internet overuse or addiction may lead to significant adverse consequences such as sleep disturbance, psychological and physical problems leading to academic decline. Although many studies have been conducted regarding internet addiction in India, nevertheless, not much has been studied in the state of Rajasthan in this regard. Hence, the present study was planned to investigate the pattern and prevalence of internet usage in young adults and its relationship with insomnia and depression in college-going youth.

Material and Method

This cross-sectional study included 1000 students of both sexes using the internet for the past 6 months from different streams in the University of Rajasthan and affiliated colleges. Formula n = z 2 × pq/d 2 was used to determine the study sample size where n represents a total number of sample, z corresponds to value at 95% confidence interval, P stands for the prevalence of internet addiction in the previous study i.e. almost 44 percent,[ 13 ] and d represents allowable error. Thus, a sample size of about 600 students was considered appropriate. This study included 1000 students out of which 46 students opted out in the middle of the study, hence 954 students finally constituted the study sample. The study participants were selected using simple random sampling. Approval was obtained from the concerned authority. Participants were informed about the nature and purpose of the study before including them in the study.

Only those participants constituted the study group who had been using the internet for the past 6 months and were willing to participate in the study. Those who did not choose to participate, having major medical or surgical problems, history of psychosis or mania, MDD, or any other mental disorder were excluded from the study.

Information was collected on a specially designed semi-structured performa containing details of demographics, educational qualification, and status, purpose of using the internet (by choosing among the options like education, entertainment, social networking or other purpose), money spent per month, place of access (home, cybercafé, or workplace if working part-time), the time of day when the internet is accessed the most (by choosing between morning, afternoon, evening, or night), and the average duration of use per day.

Internet addiction, depression, and insomnia were assessed on IAT, patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9), and insomnia severity index (ISI), respectively.

Internet addiction test (IAT)

The IAT[ 3 ] is a 20-item 5-point Likert scale that measures the severity of self-reported compulsive use of the internet. According to Young's criteria, total IAT scores 20–39 represent average users with complete control of their internet use, scores 40–69 represent over-users with frequent problems caused by their internet use, and scores 70–100 represent the internet addicts with significant problems caused by their internet use.

Patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9)

A self-report version of PRIME-MD11 which assesses the presence of major depressive disorder using modified diagnostic and statistical manual, fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria.[ 14 ] In this study, the Hindi version of PHQ-9 was used. It has been validated in the Indian population and is considered to be a reliable tool for the diagnosis of depression. For the diagnosis of depression, we define clinical significant depression as a PHQ-9 score of 8–9 as minor depression, a PHQ-9 score of 10 or greater as moderate depression; a score of 15 or more and one of the two cardinal symptoms (either depressed mood or anhedonia) as definite major depression. We considered PHQ 9 score of 10 or more as depression in this study.

Insomnia severity index (ISI)

ISI is one of the most commonly used disease-specific measures for self-perceived insomnia severity. The ISI has 7 items describing insomnia-related health impairments.[ 15 ] Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale. In clinical assessments, the ISI total summary score falls into 1 of 4 ISI categories; with scores 0–7, 8–14, 15–21, and 22–28 indicating no clinically significant insomnia, sub-threshold insomnia, moderate insomnia and, clinically severe insomnia, respectively.

We used the Hindi version of the ISI[ 16 ] Clinically, significant insomnia was detected only when the ISI score was >14.

Statistical analysis

All data collected were entered into the Microsoft excel 2007 worksheet in the form of a master chart. These data were classified and analyzed as per the aims and objectives. The data on sample characteristics were described in the form of tables. Categorical variables were tabulated using frequencies and percentages. Inferential statistics such as the Chi-square test were used to find out the association of internet usage with various factors. Odds ratio (OR) was used to find out the association of insomnia and PHQ levels with internet usage.

This study was a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study conducted among university students from different faculties.

Around 954 subjects with age ranging from 17 to 34 years were included in this study. The mean age was 23.81 years with a 3.72 standard deviation. Males were 578 (60.59%) and females were 376 (39.41%). Out of total subjects, 412 (43.19%) were internet over users and 148 (15.51%) were addicts [ Table 1 ].

Out of 954 subjects, 537 were postgraduates while 417 were undergraduates [ Table 2 ]. Among postgraduates (PG) 96 (17.88%) had internet addiction and 241 (44.88%) were over users, whereas the proportion of internet addicts and over users among undergraduates (UG) was 12.47% and 41.01%, respectively [ Table 3 ]. This association was statistically significant. Similarly, on application of Chi-square test, significant association was found between place of internet usage and addiction as 68 (25.19%) subjects were addicted and 128 (47.41%) were over users among those who were using internet at workplace as compared to 141 (16.51%) addicts and 360 (47.41%) over users among those using it at home. In this study, 86 subjects were smokers and 88 were alcoholics and the association of these personal habits and internet usage was also significant on the application of the Chi-square test. Out of them 86 smokers, 27 (31.40%) were addicted and 34 (39.53%) were over users and out of 88 alcoholics, 10 (11.36%) were addicted and 45 (51.14%) were over users. Considering duration of internet usage, it was observed that those using internet for more than 2 h a day were more addicted and over users [ 85 (19.81%) and 188 (43.82%), respectively] as compared to those using internet for less than 2 h a day [ 63 (12%) and 224 (42.67%), respectively] and this association was found significant. A total of 437 (45.81%) subjects reported insomnia among whom 107 ((24.49%) were internet addicts and 241 (55.15%) were over users whereas those subjects without insomnia comprised only 47 (7.93%) addicts and 171 (33.08%) over users. This association was again statistically significant. Similar results were noted with regard to the presence of depression. Depression was reported in 421 (44.13%) subjects including 113 (26.84%) internet addicts and 225 (53.44%) over users. Among those subjects without depression number of internet addicts and over users was 35 (6.58%) and 187 (34.96%), respectively. This observation was statistically significant.

On the application of OR considering internet usage as exposure, it was observed that chances of insomnia were more than five times on the internet over users as compared to average users [OR = 5.62 (4.20 to 7.53)]. Similarly, the estimated risk of PHQ ≥10 was observed more than five times on the internet over users as compared to average users. [OR = 5.70 (4.25 to 7.67]) [ Table 4 ].

The present study is an attempt to understand the pattern of internet use and the prevalence of internet addiction in youth college students. The mean age of the study population was 23.8 years.

Our study showed 15.5% of students with internet addiction. Wide variations ranging from 1.6% to 18% in the prevalence of internet addiction among adolescents have been reported.[ 4 ]

Prevalence of PIU (problematic internet use) among adolescents in a multicentric study in Europe was reported ranging from 1.2% to 11.8%.[ 5 ]

Another study on Indian adolescents reported the prevalence of possible addicts and addicts as 24.8% and 0.7%, respectively.[ 7 ] Similarly Kawabe et al .[ 17 ] in his study among 853 adolescents in Japan determined the prevalence of internet addiction using IAT. The prevalence of possible addicts and addicts was 21.7% and 2.0%, respectively.

In the present study boys were more internet addicts and over user than the girls. Similar observations have been made in several other studies in the past.[ 18 ] Since boys are given more liberty in our society and have more frequent access to use the internet in private than the girls predisposing them to become an addict and over the user. Studies have also shown that boys tend to play more online games and surf adult sites more often than girls.[ 19 ] Male also tend to use more addictive substances than female and it has also been reported in a meta-analysis of internet addiction that a person with a history of addiction to other substances is at higher risk of internet addiction.[ 20 ]

Internet addiction and overuse were more prevalent in postgraduate students than undergraduates. Kwabe et al .[ 17 ] has also reported that the number of students with internet addiction increases as their grades increase. Likewise, XinM.[ 21 ] in his study of 6468 Chinese adolescents also observed more internet addiction among older grade students. It is possible that the study course in PG is more demanding to access the internet and the affordability in this group to bear the expenses of the internet is much stronger than UG. It was also evident in general that educational activity was the most commonly cited purpose for internet use.

The workplace was the most preferred area for internet use among addicts. Goel et al .[ 7 ] in his study has also yielded similar results. Lesser restriction, a company of colleagues, and accessibility to free internet may have been the possible reason for this observation.

Alcohol consumption and smoking were significantly associated with internet addiction in the present study. Several other studies in the past have made similar observations where pathological internet use (PIU) or internet addiction was possibly associated with alcohol and smocking.[ 22 ]

Sung et al .[ 23 ] in his analysis of a large study sample of adolescents established a positive association of internet addiction with alcohol and smoking. Neuropsychological explanation proposes that nicotine and alcohol shares a common reward pathway.[ 24 ] which may also include the nature of internet usage as observed in many studies for e.g. striatal activation in online games when confronted with cues from their favorite games.[ 25 ] Studies have also suggested that adolescents with internet addiction may have personalities vulnerable to any other addiction and hence are at increased risk of substance abuse.[ 26 ]

In this study mean daily time spent on internet use was positively correlated with internet addiction. In a review of research on internet addiction, people at risk of internet addiction were reported to have spent significantly more time online.[ 27 ] In another study by Kuss[ 19 ] daily use of the internet and increased time online was positively correlated with internet addiction.

This study revealed a strong positive association between internet addiction and insomnia. Similar results were also established by Bhandari et al .[ 28 ] in his study of 984 undergraduate students, who reported 35.4% of the study sample having poor sleep quality and internet addiction as well. Cheung[ 29 ] in his study of 719 Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong observed high comorbidity between internet addiction and insomnia; 51.7% of students among internet addicts were insomniacs.

Association between internet addiction and depression in this study corresponds to another study among university students in Turkey by Orsala et al .[ 30 ] who reported an alarming association between internet addiction and depression. A high score of depression has also been reported in a study among Indian adolescents with internet addiction.[ 7 31 32 ] In an article on association between internet addiction and depression, the authors after taking into account several studies proposed four models of such association including escape model, bidirectional model, negative consequence model, and shared mechanism model. Grossly the association between internet addiction and psychological problems including depression are reported to have an interdependent relationship. Depression may lead to internet addiction and vice versa. Internet use in this population serves as a remedy to overcome their problems and negative perception about the situation. Such use over a period of time becomes a habit and eventually addiction, as some positive emotions like happiness and excitement are felt while being on the internet. When internet addict does not use the internet, negative emotions flare up and can only be replaced by positive emotions by using the internet.[ 8 ]

The association between internet addiction, insomnia, and depression was explored in a study that observed that internet addiction and sleep quality independently mediated 16.5% and 30.9% indirect effect of each other on depression.[ 28 ]

Internet addiction among youth has become increasingly a great concern. Various parameters including gender, time spent on the internet, graduation level, place of internet use, smoking, and alcohol have been associated with internet addiction. In addition, insomnia and depression are more common in internet addicts and may have a bidirectional relationship.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflict of interest.

There is no conflict of interest.

- Cited Here |

- Google Scholar

Depression; insomnia; internet addiction

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Advertisement

Internet addiction among college students: Some causes and effects

- Published: 27 March 2019

- Volume 24 , pages 2863–2885, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Meltem Huri Baturay ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2402-6275 1 na1 &

- Sacip Toker 2 na1

7675 Accesses

43 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Internet addiction among college students in terms of causes and effects are investigated. Correlation study method is utilized; structural equation modelling is applied to analyze the data. There are fifteen hypotheses generated for the model. The data is collected via numerous instruments proven as reliable and valid by the previous studies. There are 159 undergraduate students as participants of the study. Antecedent variables are game addiction, bad relationships with friends, family and professors, neglecting daily chores, hindrance of sleep pattern, use internet for researching, weekly internet use hours, leisure time activities, reading and playing computer games. Consequence variables are self-esteem, self-confidence, social self-efficacy, loneliness, and academic self-efficacy. The results indicates that game addiction, neglecting daily chores, bad relationships with professors are significantly associated with internet addiction. Internet addiction decreases one’s self-esteem, self-confidence, social self-efficacy, academic self-efficacy and triggers loneliness. Parents, professors and educational institutions may be illuminated about prevention or monitoring of internet addiction. The current study investigates Internet addiction with respect to its implications for social behavioral, and psychological phenomenon but not in a clinical sense. Hence, studies on Internet addiction merely concentrate on antecedents and features that may cause more addiction; however, both antecedents and consequences are not examined. The value of the current study is to provide more systematic, comprehensive, and theory-based empirical causations via structural equation models. The model may help to diagnose Internet Addiction and illuminate college students its potential harmful socio-psychological consequences.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Prevalence and associated factors of internet addiction among undergraduate university students in Ethiopia: a community university-based cross-sectional study

Internet Dependence in High School Student

Internet Addiction

Adiele, I., & Olatokun, W. (2014). Prevalence and determinants of Internet addiction among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 31 , 100–110.

Article Google Scholar

Akın, A. (2007). “Öz-güven Ölçeğinin Geliştirilmesi ve Psikometrik Özellikleri” [The development and psychometric characteristics of the self-confidence scale]. Abant İzzet Baysal Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 7 (2), 167–176.

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Armstrong, L., Phillips, J. G., & Saling, L. L. (2000). Potential determinants of heavier internet usage. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 53 (4), 537–550.

Google Scholar

Bai, Y.-M., Lin, C.-C., & Chen, J.-Y. (2001). Internet addiction disorder among clients of a virtual clinic. Psychiatric Services, 52 (10), 1397–1397.

Beard, K. W. (2005). Internet addiction: A review of current assessment techniques and potential assessment questions. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8 (1), 7–14.

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Beard, K. W., & Wolf, E. M. (2001). Modification in the proposed diagnostic criteria for internet addiction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 4 (3), 377–383.

Berry, M. J. A., & Linoff, G. S. (2000). Mastering data mining . New York: Wiley.

Brown, T. A. (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research . New York: Guilford Publications.

Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PR, and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming . Mahwah: Psychology Press.

Book Google Scholar

Byrne, B. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS . New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315757421 .

Byun, S., Ruffini, C., Mills, J. E., Douglas, A. C., Niang, M., Stepchenkova, S., & Atallah, M. (2009). Internet addiction: Metasynthesis of 1996-2006 quantitative research. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12 (2), 203–207.

Çakır, Ö., Ayas, T., & Horzum, M. B. (2011). An investigation of university students’ internet and game addiction with respect to several variables. Ankara University, Journal of Faculty of Educational Sciences, 44 (2), 95–117.

Cao, F., & Su, L. (2007). Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: Prevalence and psychological features. Child: Care, Health and Development, 33 (3), 275–281.

Caplan, S. E. (2002). Problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being: Development of a theory-based cognitive–behavioral measurement instrument. Computers in Human Behavior, 18 (5), 553–575.

Caplan, S. E. (2003). Preference for online social interaction a theory of problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being. Communication Research, 30 (6), 625–648.

Caplan, S. E. (2005). A social skill account of problematic internet use. Journal of Communication, 55 (4), 721–736.

Carli, V., Durkee, T., Wasserman, D., Hadlaczky, G., Despalins, R., Kramarz, E., et al. (2012). The association between pathological internet use and comorbid psychopathology: A systematic review. Psychopathology, 46 (1), 1–13.

Chak, K., & Leung, L. (2004). Shyness and locus of control as predictors of internet addiction and internet use. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7 (5), 559–570.

Chen, Y.-F., & Peng, S. S. (2008). University students' internet use and its relationships with academic performance, interpersonal relationships, psychosocial adjustment, and self-evaluation. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11 (4), 467–469.

Chou, C. (2001). Internet heavy use and addiction among Taiwanese college students: An online interview study. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 4 (5), 573–585.

Chou, C., Condron, L., & Belland, J. C. (2005). A review of the research on internet addiction. Educational Psychology Review, 17 (4), 363–388.

Cole, S. H., & Hooley, J. M. (2013). Clinical and personality correlates of MMO gaming: Anxiety and absorption in problematic internet use. Social Science Computer Review, 31 (4), 424–436.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

D.E.A.R. (n.d.). Drop Everything and Read, a vailable at: http://www.dropeverythingandread.com/NationalDEARday.html . Accessed 3 Sep 2015.

Demetrovics, Z., Szeredi, B., & Rózsa, S. (2008). The three-factor model of internet addiction: The development of the problematic internet use questionnaire. Behavior Research Methods, 40 (2), 563–574.

Demir, A. (1989). UCLA Yalnızlık Ölçeği’nin Geçerlik ve Güvenirliği. Psikoloji Dergisi, 7 (23), 14–18.

Dhir, A., Chen, S., & Nieminen, M. (2015). Psychometric validation of the compulsive internet use scale relationship with adolescents’ demographics, ICT accessibility, and problematic ICT use. Social Science Computer Review, 34 (2), 197–214.

Diamantopoulos, A., & Siguaw, J. A. (2013). Introducing LISREL: A guide for the uninitiated . London: Sage Publications.

DiNicola, M. D. (2004). Pathological internet use among college students: The prevalence of pathological internet use and its correlates. Diss. Ohio University, Ohio, US.

Doğan, A. (2013). İnternet Bağımlılığı Yaygınlığı [ Prevalence of Internet Addiction ]. Unpublished Manuscript, Dokuz Eylül University, İzmir, Turkey.

Fanning, P., & O'Neill, J. T. (1996). The addiction workbook: A step-by-step guide for quitting alcohol and drugs . Oakland: New Harbinger Publications.

Ferraro, G., Caci, B., D'amico, A., & Blasi, M. D. (2006). Internet addiction disorder: An Italian study. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10 (2), 170–175.

Ghassemzadeh, L., Shahraray, M., & Moradi, A. (2008). Prevalence of internet addiction and comparison of internet addicts and non-addicts in Iranian high schools. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11 (6), 731–733.

Griffiths, M. D. (1991). Amusement machine playing in childhood and adolescence: A comparative analysis of video games and fruit machines. Journal of Adolescence, 14 (1), 53–73.

Griffiths, M. D. (2000). Does internet and computer "addiction" exist? Some case study evidence. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 3 (2), 211–218.

Griffiths, M. D. (2008). Videogame addiction: Further thoughts and observations. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 6 (2), 182–185.

Griffiths, M., Kuss, J. D., & King, D. L. (2012). Video game addiction: Past, present and future. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 8 (4), 308–318.

Günüç, S. (2009). İnternet bağımlılık ölçeğinin geliştirilmesi ve bazı demografik değişkenler ile internet bağımlılığı arasındaki ilişkilerin incelenmesi [ Development of Internet Addiction Scale and scrutinising the relations between the internet addiction and some demographic variables ], Master Thesis, Yüzüncü Yıl University, Van, Turkey.

Günüç, S. (2015). Relationships and associations between video game and internet addictions: Is tolerance a symptom seen in all conditions. Computers in Human Behavior, 49 (C), 517–525.

Han, J., & Kamber, M. (2000). Data mining: Concepts and techniques . New York: Morgan-Kaufman.

MATH Google Scholar

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6 (1), 53–60.

Horzum, M. B., Aras, T., & Çakır Balta, Ö. (2008). Çocuklar için Bilgisayar Oyun Bağımlılığı Ölçeği. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi, 3 (30), 76–88.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6 (1), 1–55.

Huang, R. L., Lu, Z., Liu, J. J., You, Y. M., Pan, Z. Q., Wei, Z., He, Q., & Wang, Z. Z. (2009). Features and predictors of problematic internet use in Chinese college students. Behaviour & Information Technology, 28 (5), 485–490.

Jerusalem, M., & Schwarzer, R. (1981). “Fragebogen zur Erfassung von” Selbstwirksamkeit. Skalen zur Befindlichkeit und Persoenlichkeit. Forschungsbericht No. 5. Berlin: Freie Universitaet, Institut fuer Psychologie .

Jiang, Q. (2014). Internet addiction among young people in China: Internet connectedness, online gaming, and academic performance decrement. Internet Research, 24 (1), 2–20.

Jiang, Q., & Leung, L. (2012). Effects of individual differences, awareness-knowledge, and acceptance of internet addiction as a health risk on willingness to change internet habits. Social Science Computer Review, 30 (2), 170–183.

Johansson, A., & Götestam, K. G. (2004). Internet addiction: Characteristics of a questionnaire and prevalence in Norwegian youth (12–18 years). Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 45 (3), 223–229.

Kandell, J. J. (1998). Internet addiction on campus: The vulnerability of college students. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 1 (1), 11–17.

Keller, J. M. (1987). The systematic process of motivational design. Performance and Instruction, 26 (9–10), 1–8.

Keller, J. M. (2009). Motivational Design for Learning and Performance: The ARCS model approach . New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

Kim, J., LaRose, R., & Peng, W. (2009). Loneliness as the cause and the effect of problematic internet use: The relationship between internet use and psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12 (4), 451–455.

Ko, C.-H., Yen, J.-Y., Chen, C.-C., Chen, S.-H., & Yen, C.-F. (2005). Gender differences and related factors affecting online gaming addiction among Taiwanese adolescents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193 (4), 273–277.

Ko, C.-H., Yen, J.-Y., Yen, C.-F., Lin, H.-C., & Yang, M.-J. (2007). Factors predictive for incidence and remission of internet addiction in Young adolescents: A prospective study. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10 (4), 545–551.

Ko, C.-H., Yen, J.-Y., Chen, S.-H., Yang, M.-J., Lin, H.-C., & Yen, C.-F. (2009). Proposed diagnostic criteria and the screening and diagnosing tool of internet addiction in college students. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50 (4), 378–384.

Ko, C. H., Wang, P. W., Liu, T. L., Yen, C. F., Chen, C. S., & Yen, J. Y. (2014). Bidirectional associations between family factors and internet addiction among adolescents in a prospective investigation. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 69 (4), 192–200.

Kormas, G., Critselis, E., Janikian, M., Kafetzis, D., & Tsitsika, A. (2011). Risk factors and psychosocial characteristics of potential problematic and problematic internet use among adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 11 , 595.

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukophadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53 (9), 1017–1031.

Kubey, R. W., Lavin, M. J., & Barrows, J. R. (2001). Internet use and collegiate academic performance decrements: Early findings. Journal of Communication, 51 (2), 366–382.

Kurtaran, G. T. (2008). Examining the variables predicted internet addiction . Master’s Thesis, Mersin University, Mersin, Turkey.

Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., Karila, L., & Billieux, J. (2014). Internet addiction: A systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20 (25), 4026–4052.

Lei, L., & Hongli, L. (2003). Definition and measurement on pathological internet use. Advances in Psychological Science, 11 (01), 73–77.

Leung, L., & Lee, P. S. (2012). Impact of internet literacy, internet addiction symptoms, and internet activities on academic performance. Social Science Computer Review, 30 (4), 403–418.

Liu, C.-Y., & Kuo, F.-Y. (2007). A study of internet addiction through the lens of the interpersonal theory. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10 (6), 799–804.

Loytsker, J., & Aiello, J. R. (1997). Internet addiction and its personality correlates. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Eastern Psychological Association, Washington, DC Vol. 11.

Miles, J., & Shevlin, M. (2007). A time and a place for incremental fit indices. Personality and Individual Differences, 42 (5), 869–874.

Morahan-Martin, J. (1999). The relationship between loneliness and internet use and abuse. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 2 (5), 431–439.

Morahan-Martin, J., & Schumacher, P. (2000). Incidence and correlates of pathological internet use among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 16 (1), 13–29.

Müller, K. W., Glaesmer, H., Brähler, E., Woelfling, K., & Beutel, M. E. (2014). Prevalence of internet addiction in the general population: Results from a German population-based survey. Behaviour & Information Technology, 33 (7), 757–766.

Nalwa, K., & Anand, A. P. (2003). Internet addiction in students: A cause of concern. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 6 (6), 653–656.

Ni, X., Yan, H., Chen, S., & Liu, Z. (2009). Factors influencing internet addiction in a sample of Freshmen University students in China. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12 (3), 327–330.

Park, S. K., Kim, J. Y., & Cho, C. B. (2007). Prevalence of internet addiction and correlations with family factors among south Korean adolescents. Adolescence, 43 (172), 895–909.

Pişkin, M. (1996). Self-esteem and locus of control of secondary school children both in England and Turkey . Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leicester.

Pratarelli, M. E., Browne, B. L., & Johnson, K. (1999). The bits and bytes of computer/internet addiction: A factor analytic approach. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 31 (2), 305–314.

Prisbell, M. (1988). Dating competence as related to levels of loneliness. Communication Reports, 1 (2), 54–59.

Rehbein, F., & Mößle, T. (2013). Video game and internet addiction: Is there a need for differentiation? SUCHT-Zeitschrift Für Wissenschaft Und Praxis/Journal of Addiction Research and Practice, 59 (3), 129–142.

Rumpf, H. J., Vermulst, A. A., Bischof, A., Kastirke, N., Gürtler, D., Bischof, G., Meerkerk, G. J., John, U., & Meyer, C. (2014). Occurence of internet addiction in a general population sample: A latent class analysis. European Addiction Research, 20 (4), 159–166.

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66 (1), 20–40.

Russell, D. W., Peplau, L. A., & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42 (3), 290–294.

Sanders, C. E., Field, T. M., Diego, M., & Kaplan, M. (2000). The relationship of internet use to depression and social isolation among adolescents. Adolescence, 35 (138), 237–242.

Sherer, K. (1997). College life on-line: Healthy and unhealthy internet use. Journal of College Student Development, 38 (6), 655–665.

Shotton, M. A. (1991). The costs and benefits of ‘computer addiction’. Behaviour & Information Technology, 10 (3), 219–230.

Sinkkonen, H.-M., Puhakka, H., & Meriläinen, M. (2014). Internet use and addiction among Finnish adolescents (15-19 years). Journal of Adolescence, 37 (2), 123–131.

Siomos, K. E., Dafouli, E. D., Braimiotis, D. A., Mouzas, O. D., & Angelopoulos, N. V. (2008). Internet addiction among Greek adolescent students. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11 (6), 653–657.

Smahel, D., Brown, B. B., & Blinka, L. (2012). Associations between online friendship and internet addiction among adolescents and emerging adults. Developmental Psychology, 48 (2), 381–388.

Stats, I. W. (2014). World Internet Users and 2014 Population Stats available at: http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm . Accessed 02 March 2015.

Steiger, J. H. (2007). Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personality and Individual Differences, 42 (5), 893–898.

Suler, J. (2004). Computer and cyberspace “addiction”. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 1 (4), 359–362.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Tahiroglu, A. Y., Celik, G. G., Uzel, M., Ozcan, N., & Avci, A. (2008). Internet use among Turkish adolescents. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11 (5), 537–543.

Tang, J., Yu, Y., Du, Y., Ma, Y., Zhang, D., & Wang, J. (2014). Prevalence of internet addiction and its association with stressful life events and psychological symptoms among adolescent internet users. Addictive Behaviors, 39 (3), 744–747.

Tokunaga, R. S., & Rains, S. A. (2010). An evaluation of two characterizations of the relationships between problematic internet use, time spent using the internet, and psychosocial problems. Human Communication Research, 36 (4), 512–545.

Tsai, C.-C., & Lin, S. S. (2001). Analysis of attitudes toward computer networks and internet addiction of Taiwanese adolescents. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 4 (3), 373–376.

Vidyachathoth, K. B., Kumar, N. A., & Pai, S. R. (2014). Correlation between affect and internet addiction in undergraduate medical students in Mangalore. Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy, 5 (1), 175–178.

Walker, M. B. (1989). Some problems with the concept of “gambling addiction”: Should theories of addiction be generalized to include excessive gambling? Journal of Gambling Behavior, 5 (3), 179–200.

Wallace, P. (2014). Internet addiction disorder and youth. EMBO Reports, 15 (1), 12–16.

Whang, L. S.-M., Lee, S., & Chang, G. (2003). Internet over-users' psychological profiles: A behavior sampling analysis on internet addiction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 6 (2), 143–150.

Wheaton, B., Muthen, B., Alwin, D. F., & Summers, G. F. (1977). Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociological Methodology, 8 , 84–136.

Widyanto, L., & Griffiths, M. (2006). ‘Internet addiction’: A critical review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 4 (1), 31–51.

Widyanto, L., & McMurran, M. (2004). The psychometric properties of the internet addiction test. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7 (4), 443–450.

Witten, I. H., & Frank, E. (2000). Data mining . New York: Morgan-Kaufmann.

Yan, W., Li, Y., & Sui, N. (2014). The relationship between recent stressful life events, personality traits, perceived family functioning and internet addiction among college students. Stress and Health, 30 (1), 3–11.

Yang, L., Sun, L., Zhang, Z., Sun, Y., Wu, H., & Ye, D. (2014). Internet addiction, adolescent depression, and the mediating role of life events: Finding from a sample of Chinese adolescents. International Journal of Psychology, 49 (5), 342–347.

Yao, M. Z., & Zhong, Z.-J. (2014). Loneliness, social contacts and Internet addiction: A cross-lagged panel study. Computers in Human Behavior, 30 , 164–170.

Yao, M. Z., He, J., Ko, D. M., & Pang, K. (2014). The influence of personality, parental behaviors, and self-esteem on internet addiction: A study of Chinese college students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17 (2), 104–110.

Yen, J.-Y., Yen, C.-F., Chen, C.-C., Chen, S.-H., & Ko, C.-H. (2007). Family factors of internet addiction and substance use experience in Taiwanese adolescents. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10 (3), 323–329.

Yen, C.-F., Chou, W.-J., Liu, T.-L., Yang, P., & Hu, H.-F. (2014). The Association of Internet Addiction Symptoms with anxiety, depression and self-esteem among adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55 (7), 1601–1608.

Yılmaz, M., Gürçay, D., & Ekici, G. (2007). Akademik özyeterlik ölçeğinin Türkçe’ye uyarlanması. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 33 , 253–259.

Young, K. S. (1998a). Caught in the net: How to recognize the signs of internet addiction--and a winning strategy for recovery . New York: Wiley.

Young, K. S. (1998b). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 1 (3), 237–244.

Young, K. S. (1999). Internet addiction: Symptoms, evaluation and treatment. In Innovations in clinical practice: A source book (Vol. 17, pp. 19–31).

Young, K. S., & Rodgers, R. C. (1998). Internet addiction: Personality traits associated with its development. In Paper presented at the 69th annual meeting of the Eastern Psychological Association, Boston .

Young, K. S., & Rogers, R. C. (1998). The relationship between depression and internet addiction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 1 (1), 25–28.

Yung, K., Eickhoff, E., Davis, D. L., Klam, W. P., & Doan, A. P. (2015). Internet addiction disorder and problematic use of Google glass™ in patient treated at a residential substance abuse treatment program. Addictive Behaviors, 41 , 58–60.

Download references

Author information

Meltem Huri Baturay and Sacip Toker contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

School of Foreign Languages, Department of Basic English, Atılım University, İncek, Ankara, Turkey

Meltem Huri Baturay

School of Engineering, Department of Information Systems, Atılım University, İncek, Ankara, Turkey