An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Respir Med Case Rep

Case report: Three adult brothers with cystic fibrosis (delF508-delF508) maintain unusually preserved clinical profile in the absence of standard CF care

We present three cases in this report. Three adult brothers, homozygous for the delF508 cystic fibrosis mutation, have maintained an unusually preserved clinical condition even though they did not attend a CF Clinic during their childhood, do not attend a CF Clinic now, and do not follow standard CF care guidelines. The brothers use an alternative CF treatment regimen on which they have maintained normal lung function, height/weight, and bloodwork, and they utilize less than half the recommended dosage of pancreatic enzymes. The brothers culture only methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, and have never cultured any other bacteria. Highly effective modulator therapies, such as elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor, do not substantially reduce infection and inflammation in vivo in CF patients, and thus these three case reports are of special note in terms of suggesting adjunct therapeutic approaches. Finally, these three cases also raise important questions about standard CF care guidelines.

- • Three adult brothers, delF508 cystic fibrosis (CF) homozygotes, maintain unusually preserved clinical condition absent standard CF care.

- • An alternative CF treatment regimen has kept their lung function, weight/height, and lab parameters normal, with low pancreatic enzyme dose.

- • The brothers culture only methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, and have never cultured any other bacteria.

- • Highly effective modulator therapies (HEMT) for CF do not substantially reduce infection and inflammation in vivo; these cases are thus of note.

- • These cases also raise important questions about standard CF care guidelines.

1. Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a serious and life-shortening genetic disorder affecting approximately 70,000 persons worldwide [ 1 ]. Respiratory failure is the foremost cause of death in CF patients, and lung transplantation is often considered in end-stage CF disease. For those born with CF in the last five years, median predicted survival age is now 44, which is decades longer than survival rates in the recent past [ 2 ]. Indeed, new advances in CF modulator therapy and CF gene therapy may eventually provide a normal life expectancy for these individuals.

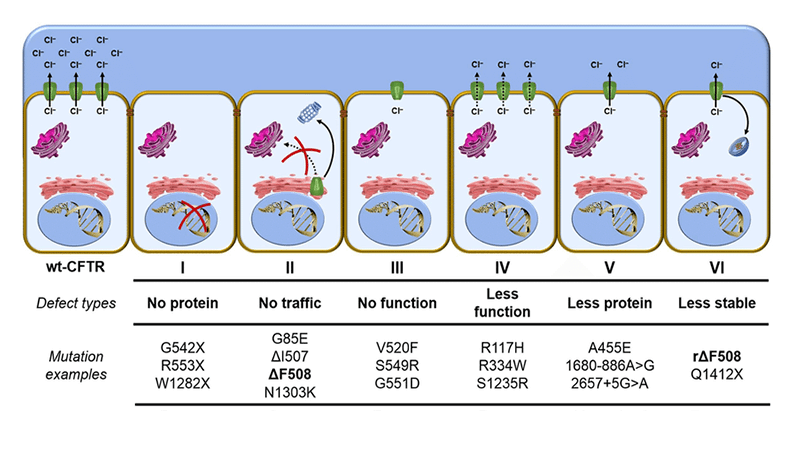

A key approach in fighting the ravages of CF while waiting for more advanced treatments to be developed has been to slow the inexorable decline in lung function. Typical rate of lung function decline in CF is approximately −1.2 to −1.6 FEV1% per year [ 3 ]. Rate of decline is strongly associated with type of CF mutation. The three most severe classes of CFTR, Classes I, II, and III, represent defects in protein production, protein processing, and protein regulation, respectively [ 4 ]. The most common CF-causing mutation is delF508, occurring in 70% of cases, which is a Class II mutation [ 5 ]. Being homozygous for the delF508 mutation confers a severe phenotype, including pancreatic insufficiency and a steeper rate of decline in lung function over time [ 6 ]. In the United States, it is estimated that approximately 50% of those with cystic fibrosis are homozygous for delF508 [ 7 ]. Standard clinical care for severe mutation cases is often aggressive, including but not limited to daily airway clearance, use of pancreatic enzymes at the level of 500-2,500 lipase units/kg/meal (and enteric feeding if adequate weight percentile cannot be maintained), common and repeated use of oral, inhaled and intravenous antibiotics, daily intake of water-miscible versions of fat-soluble vitamins, and quarterly CF Clinic visits where lung function parameters and cultures of lung bacteria and fungi are assessed [ 8 , 9 ]. Pulmonary exacerbations often result in hospitalization, which may occur one or more times per year, typically lasting 14–21 days and including intensive antibiotic treatment and chest physical therapy. Everyday treatment burden is high, with estimates of 2–3 hours per day, with adherence at an estimated 50% or less [ 10 ]. The mean annual cost of standard supportive CF care in the US in 2016 (in 2019 dollars), before CFTR modulator therapies, was estimated to average $77,143, with severe non-transplant cases experiencing multiple pulmonary exacerbations costing on average triple or quadruple that amount [ 11 ]. With the average cost of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor (Trikafta) treatment currently over $311,000 per year, average standard supportive CF care costs were expected to double in 2019 [ 12 ] and increase further over time, perhaps quadrupling, with wider adoption of that treatment by all eligible patients.

Here we report on three adult brothers who are delF508 homozygotes, and yet who have maintained an unusually preserved clinical profile in the absence of standard CF clinical care. At the time of this writing, Brother A is 23 years old, Brother B is 21 years old, and Brother C is 18 years old. They are full-blooded siblings.

2. Case reports

2.1. brother a.

Brother A, now aged 23, was born full-term weighing 10 lbs. 2 oz. to a carrier mother experiencing gestational diabetes who subsequently breastfed him. His weight percentile decreased significantly over time, and at 6 months, after a course of oral antibiotics for a suspected ear infection, he developed a severe Vitamin K deficiency manifesting in quarter-sized black bruises on his body, as well as Pseudo-Bartter Syndrome. He was hospitalized until IV fluids stabilized his condition and normalized his electrolytes. Vitamin K shots were also administered. At 9 months of age, he was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis, and the genetic mutation analysis identified him as a delF508 homozygote. Between the time of his hospitalization and his diagnosis, he suffered from malnutrition with accompanying protein edema and his weight percentile, which had been over 97th percentile when born, was under the 5th percentile adjusted for age and sex. Once started on pancreatic enzymes (CREON 5) after diagnosis, his weight percentile increased to approximately the 30th percentile.

Approximately one year after diagnosis, the parents of Brother A elected to depart from standard CF care, including an election to stop attending the CF Clinic, while continuing to be under the care of their family pediatrician. The treatment plan for the brothers is described in detail in a later section. The only prescription medicine taken during his childhood and continuing to this day remains CREON 5/6, with Brother A utilizing 4 CREON 5/6 per meal, less than half the lowest recommended dose for his weight. In the teen years, Brother A experienced three episodes of heat exhaustion requiring IV fluid stabilization in an emergency room, has had one endoscopic sinus cleaning for sinus pain at age 20, and also underwent an appendectomy for appendicitis at age 23, but otherwise has had no major clinical issues, though exhibiting digital clubbing. Brother A played ice hockey throughout his childhood and teen years. His height, weight, lung function, and lab results at age 23 are provided in Table 1 .

Clinical parameters, Brother A.

| Brother A, age 23, delF508/delF508, all tests performed June–August 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Height, Height percentile for men | 6′0”, 84th percentile |

| Weight, Weight percentile for men | 218 lbs., 72nd percentile |

| BMI | 29.6 (overweight) |

| Blood pressure | 146/84 |

| FVC (percent predicted) | 6.95 L (124%) |

| FEV1 (percent predicted) | 5.21 L (108%) |

| FEV1/FVC (percent predicted) | 74.96% |

| PEF (percent predicted) | 14.67 L/second (about 160%) |

| %SpO | 97% |

| CF Lower Respiratory Culture (LabCorp version) | Light Growth, Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin sensitive) |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 5.2% (Normal; normal range 4.8–5.6) |

| C-Reactive Protein | <1 mg/L (Normal; normal range 0–10) |

| Vitamin D, 25-Hydroxy | 39.1 ng/mL (Normal; normal range 39–100) |

| Beta Carotene | 6 μg/dL (Normal; normal range 3–91) |

| Vitamin A | 68.8 μg/dL (High; normal range 18.9–57.3) |

| Vitamin E (Alpha Tocopherol) | 27.6 mg/L (High; normal range 5.9–19.4) |

| Vitamin E (Gamma Tocopherol) | 0.6 mg/L (Low; normal range 0.7–4.9) |

| Total Protein | 7.5 g/dL (Normal; normal range 6.0–8.5) |

| Albumin | 4.9 g/dL (Normal; normal range 4.1–5.2) |

| Bilirubin, Total | 0.5 mg/dL (Normal; normal range 0–1.2) |

| Bilirubin, Direct | 0.13 mg/dL (Normal; normal range 0–0.40) |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 100 IU/L (Normal; normal range 39–117) |

| AST (SGOT) | 24 IU/L (Normal; normal range 0–40) |

| ALT (SGPT) | 47 IU/L (High; normal range 0–44) |

2.2. Brother B

Brother B, now aged 21, was born full-term, weighing 8 lbs. 8 oz., the mother supplementing with oral glutathione (GSH) during the pregnancy and subsequently breastfeeding him. Brother B has never attended a CF Clinic, was diagnosed at 2 weeks of age, and was under the care of the family's pediatrician only. Brother B's only prescription medication during his childhood was CREON 5/6, just as with Brother A, utilizing 4 capsules per meal. Brother B has never needed to be hospitalized or have surgery or antibiotics. While Brother B does not exhibit digital clubbing; when recovering from respiratory viruses, he does manifest a cough that lingers longer than it lingers for his brothers, though the cough ultimately resolves. Brother B played ice hockey in childhood and teen years, as well as participated in gymnastics, cross-country running, track and field, and weight-lifting. His height, weight, lung function, and lab results at age 21 are provided in Table 2 .

Clinical parameters, Brother B.

| Brother B, age 21, delF508/delF508, all tests performed June–August 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Height, Height percentile for men | 5′ 10 ½”, 67th percentile |

| Weight, Weight percentile for men | 157.8 lbs, 19th percentile |

| BMI | 22.3 (normal) |

| Blood pressure | 122/70 |

| FVC (percent predicted) | 4.81 L (133%) |

| FEV1 (percent predicted) | 3.13 L (101%) |

| FEV1/FVC (percent predicted) | 65.07% |

| PEF (percent predicted) | 6.75 L/second (93%) |

| %SpO | 92% |

| CF Lower Respiratory Culture (LabCorp version) | Light Growth, Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin sensitive) |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 5.3% (Normal; normal range 4.8–5.6) |

| C-Reactive Protein | <1 mg/L (Normal; normal range 0–10) |

| Vitamin D, 25-Hydroxy | 34.9 ng/mL (Normal; normal range 0–100) |

| Beta Carotene | 6 μg/dL (Normal; normal range 3–91) |

| Vitamin A | 53.2 μg/dL (Normal; normal range 18.9–57.3) |

| Vitamin E (Alpha Tocopherol) | 15.4 mg/L (Normal; normal range 5.9–19.4) |

| Vitamin E (Gamma Tocopherol) | 0.3 mg/L (Low; normal range 0.7–4.9) |

| Total Protein | 7.2 g/dL (Normal; normal range 6.0–8.5) |

| Albumin | 4.7 g/dL (Normal; normal range 4.1–5.2) |

| Bilirubin, Total | 1.0 mg/dL (Normal; normal range 0–1.2) |

| Bilirubin, Direct | 0.25 mg/dL (Normal; normal range 0–0.4) |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 88 IU/L (Normal; normal range 39–117) |

| AST (SGOT) | 24 IU/L (Normal; normal range 0–40) |

| ALT (SGPT) | 25 IU/L (Normal; normal range 0–44) |

2.3. Brother C

Brother C, now aged 18, was born full-term weighing 9 lbs. 2 oz., the mother supplementing with oral glutathione (GSH) during the pregnancy and subsequently breastfeeding him. Brother C has never attended a CF Clinic, was diagnosed at 2 weeks of age, and was under the care of the family's pediatrician only. Brother C's only prescription medication during his childhood was CREON 5/6, just as with Brothers A and B, utilizing 4 capsules per meal. Brother C has never needed to be hospitalized, or have surgery or antibiotics. Brother C does not exhibit digital clubbing. Brother C played ice hockey in childhood and teen years, as well as participated in gymnastics. His height, weight, lung function, and lab results at age 18 are provided in Table 3 .

Clinical parameters, Brother C.

| Brother C, age 18, delF508/delF508, all tests performed June–August 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Height, Height percentile for men | 5′ 11 ½ ”, 78th percentile |

| Weight, Weight percentile for men | 153.6 lbs., 15th percentile |

| BMI | 21.1 (normal) |

| Blood pressure | 121/71 |

| FVC (percent predicted) | 6.44 L (127%) |

| FEV1 (percent predicted) | 5.07 L (116%) |

| FEV1/FVC (percent predicted) | 78.73% |

| PEF (percent predicted) | 13.93 L/second (155%) |

| %SpO | 97% |

| CF Lower Respiratory Culture (LabCorp version) | Moderate Growth, Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin sensitive) |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 5.4% (Normal; normal range 4.8–5.6) |

| C-Reactive Protein | 2 mg/L (Normal; normal range 0–10) |

| Vitamin D, 25-Hydroxy | 27.9 ng/mL (Low; normal range 30–100) |

| Beta Carotene | 6 μg/dL (Normal; normal range 3–91) |

| Vitamin A | 48.4 μg/dL (Normal; normal range 18.8–54.9) |

| Vitamin E (Alpha Tocopherol) | 13.8 mg/L (High; normal range 5.0–13.2) |

| Vitamin E (Gamma Tocopherol) | 0.7 mg/L (Low; normal range 0.8–3.8) |

| Total Protein | 7.2 g/dL (Normal; normal range 6.0–8.5) |

| Albumin | 4.6 g/dL (Normal; normal range 4.1–5.2) |

| Bilirubin, Total | 0.3 mg/dL (Normal; normal range 0–1.2) |

| Bilirubin, Direct | 0.10 mg/dL (Normal; normal range 0–0.4) |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 127 IU/L (Normal; normal range 56–127) |

| AST (SGOT) | 27 IU/L (Normal; normal range 0–40) |

| ALT (SGPT) | 36 IU/L (Normal; normal range 0–44) |

3. Description of treatment

Given the severity of the genotype involved and the almost complete non-adherence to standard CF guidelines (with the exception of a significantly lower-than-average dose of prescription pancreatic enzymes and a standard dose of water-miscible fat soluble vitamins), the preserved clinical profile of these three brothers is noteworthy. However, the family developed a regimen that went well beyond pancreatic enzymes and water-miscible vitamins. The treatment regimen is provided in Table 4 .

Description of Daily Regimen.

4. Discussion

There are several possibilities for the preserved clinical status of these three brothers in the absence of standard CF care:

- a) They avoided the CF Clinic setting. Recent research [ 13 ] has shown that Pseudomonas infections are more prevalent and lung function lower among CF patients in standard care versus CF patients in a telemedicine setting. It is possible these three brothers benefitted from not attending a standard CF Clinic, especially since during their childhood years at the turn of the century, Clinic infection control was not emphasized. For example, during Brother A's first few CF Clinic visits as an infant, families were expected to wait together in a communal area with communal toys, and health care professionals at the Clinic wore neither masks nor gloves as they moved from exam room to exam room.

- b) With the exception of Brother A, Brothers B and C have used no antibiotics at all. Brother A has only used antibiotics three times in his life; the first use in infancy precipitated Pseudo-Bartter Syndrome, leading to his diagnosis with cystic fibrosis. The other two uses were incident to endoscopic sinus scraping and an appendectomy. Recent research has shown the importance of the gut microbiome in maintenance of health (including respiratory function), digestion and immune signaling, and this is true in the case of cystic fibrosis as well [ [14] , [15] , [16] ]. As David Pride, Associate Director of Microbiology at UC San Diego, notes in an address to the 2019 North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference [ 17 ], “It is important to preserve our microbiomes because they play important roles in preventing pathogens from establishing infections, in the development of our immune systems to recognize and kill pathogens, and in metabolic processes such as the digestion of foods. Indiscriminate uses of antibiotics can have profound and long-lasting effects upon our microbiomes by killing many of the bacteria that make up our microbiome; thus, limiting their use may aid in keeping us healthy.”

- Prevalent, sometimes chronic, antibiotic use among CF patients results in a significant gut dysbiosis [ 18 ]. In addition, it has been noted that aggressive antibiotic use in CF, usually incident to the first manifestation of Staphylococcus aureus (SA), may allow Pseudomonas aeruginosa a greater foothold [ 19 ], and that aggressive treatment of Pseudomonas may, in turn, promote drug resistance and may allow additional bacteria, such as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, an opportunity to proliferate [ 20 ]. Perhaps a preserved gut microbiome due to non-use of antibiotics may have played a role in the brothers' preserved clinical condition; this may also help account for the brothers’ significantly lower level of need for pancreatic enzymes. Perhaps also the decision not to aggressively treat their light to moderate growth of methicillin-sensitive SA may have precluded additional bacteria, including drug-resistant bacteria, from emerging.

- c) Other standard daily CF treatments were not employed, either, which might help account for their preserved clinical condition. For example, the brothers do not use bronchodilators; and beta-2 agonist bronchodilators, such as albuterol, have recently been shown to significantly reduce delF508 CFTR activation [ 21 ]. This reduction is even evident when CFTR modulators are used, with the finding of a more than 60% reduction of modulator-corrected CFTR activation in vitro, “sufficient to abrogate VX809/VX770 modulation of F508-del CFTR” [ 21 ]. In addition, the brothers do not use DNase, which has been associated with increased levels of neutrophil elastase in past research [ 22 ]. Last, after Brother A transitioned to his new treatment regimen at approximately 23 months of age, chest percussive therapy (CPT) was discontinued, and neither Brother B nor C underwent CPT at all. A Cochrane meta-review found that while CPT constituted the lion's share of treatment time burden in CF, the evidence that outcomes of CPT differed from no CPT was “very low quality” [ 23 ].

- d) Glutathione (GSH) is heavily emphasized in the brothers' daily regimen. Levels of GSH are strongly decreased in the extracellular milieu of CF patients, as its efflux from epithelial cells is compromised by CFTR mutation [ 24 ]. In the non-CF research literature, GSH in its ratio of reduced to oxidized forms (GSH:GSSG) has been shown to be the foundation of redox signaling in the body; GSH is also the body's primary water-soluble antioxidant and a potent mucolytic, and conserves NO through formation of GSNO. Given its pivotal roles, it is not surprising to find that GSH deficiency is noted in several other severe respiratory illnesses besides CF, including ARDS, COPD, IIP, IPF, IRDS, and DFA, and GSH deficiency is a key catalyst for (and GSH dosing a key treatment of) cachexia [ 24 ]. The use of GSH in the treatment of CF may reduce systemic inflammation, lessen the viscosity of mucus, and catalyze the efficacy of the immune system, including through GSNO. Indeed, a clinical study by Visca et al. found significantly increased BMI [ 25 ], significantly increased lung function [ 26 ], and even improved bacteriological results [ 27 ] from the daily use of oral glutathione in children with CF at a dose of 30 mg/lb body weight/day, spread out over 3–4 doses, over a time period of 6 months. In addition, the parents of these brothers noted a sudden increase in both saliva and appetite in Brother A after glutathione (GSH) was introduced when he was two years of age. Brothers B and C, on GSH from two weeks of birth (and with the mother supplementing with oral glutathione throughout pregnancy with these two brothers), never displayed low saliva or low appetite. The preserved clinical status of these three brothers may perhaps be related to this glutathione-heavy regimen.

- e) Other aspects of the brothers' regimen may offset their disease condition. The use of probiotics [ 28 ], the heavy emphasis on antioxidants in addition to glutathione (such as C, CoQ10, Alpha-lipoic acid, D, E, etc. [ 29 ]), amino acids (such as cysteine [ 30 ], carnitine [ 31 ], choline [ 32 , 33 ], taurine [ 34 ], and glycine [ 35 ]), curcumin [ 36 ], and additional digestive support beyond enzymes (lecithin, bile acid). It is possible that some or all of these supplementation efforts also helped to preserve the clinical status of the three brothers. In addition, exclusive breastfeeding of CF infants has been linked to significantly higher FEV1 at age 5 (difference significant at p ≤ 0.001 between breastfed and formula fed CF infants), perhaps contributing to the preservation of lung function beyond that time frame [ 37 ].

- f) Modifier alleles may be present. While no in-depth analysis of the brothers' genetic profile has been performed beyond the identification of their CF mutations, there are known modifier alleles that serve to lessen (or exacerbate) the severity of CF (see, for example [ 38 ]). It is possible all three brothers inherited some propitious set of modifier alleles.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, while it is encouraging and heartening that new CF therapies, such as elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor (Trikafta) and other HEMT (highly effective modulator therapies), now exist, it is instructive to consider how this family was able to preserve the clinical condition of three brothers, all delF508 homozygotes, in the absence of those therapies, and even in the absence of standard CF care. While HEMT certainly increase CFTR activity, there is substantially less effect on infection and inflammation in vivo [ 39 ]. As recently noted by Singh et al., “[I]f infection and inflammation become uncoupled from CFTR activity in established disease [due to HEMT use], drugs targeting CFTR may need to be initiated very early in life, or used in combination with agents that suppress infection and inflammation ” [ 39 ; emphasis ours]. These case reports may speak to that proposition.

Furthermore, each possible explanation for that preservation is an occasion for reflection on the current standard of CF care. We may feel to ask questions such as, “From the point of view of the patient's health, is the entire concept of the CF Clinic inherently flawed? Is the frequent, sometimes chronic, use of antibiotics and certain other medications in CF care a real double-edged sword for CF patients, with disadvantages possibly outweighing advantages in many cases? Are there measures we can take now, relatively inexpensive measures such as the use of glutathione (GSH) and other antioxidants and amino acids, that will help preserve the clinical status of CF patients, and that might synergize with cutting-edge treatments such as CFTR modulators to improve and safeguard health to an even greater degree, and which should be initiated as early in life as possible, possibly while the fetus is still in utero ?” The experience of these three brothers, so removed from standard CF care and yet so well preserved in their clinical status, highlights the need to consider such questions more urgently than we perhaps have heretofore considered them.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the Utah Valley Institute of Cystic Fibrosis, for publication costs only.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge Valerie M. Hudson, who assisted with the writing of this article.

Snapsolve any problem by taking a picture. Try it in the Numerade app?

Cell biology, a short course

Stephen r. bolsover, jeremy s. hyams, elizabeth a. shephard, hugh a. white, claudia g. wiedemann, case study: cystic fibrosis - all with video answers.

Chapter Questions

A mother and a father, both CF carriers, have two children that do not suffer from $\mathrm{CF}$. The chance of a third pregnancy producing a child with the disease is A. zero. B. 1 in 4. C. 1 in 3 . D. 1 in 2. E. very high-the child will almost certainly have $\mathrm{CF}$.

Cystic fibrosis results from a defect in a protein that forms A. a plasma membrane sodium ion channel. B. a plasma membrane potassium ion channel. C. a plasma membrane calcium ion channel. D. a plasma membrane chloride ion channel. E. a plasma membrane phenylalanine carrier.

A zoo blot helps to detect DNA sequences that A. are mutating at a fast rate. B. are conserved between species. C. show no similarity between species. D. are lost due to species extinction. E. are processed pseudogenes.

Somatic gene therapy attempts to correct a gene defect by introducing the normal gene into A. the egg. B. the sperm. C. the fertilized egg. D. cultured embryonic stem (ES) cells. E. cells in the patient's body other than eggs or sperm.

The most common mutation that causes $\mathrm{CF}$ A. is a nonsense mutation at codon 508 that causes premature chain termination of the CFTR protein. B. is a frameshift mutation such that all amino acids following phe at 508 are different from the normal protein. C. is a deletion of three nucleotides that causes phe 508 to be absent in the mutant protein. D. is a nonsense mutation causing failure to express a receptor tyrosine kinase whose activation triggers expression of the proteins mediating chloride transport. E. only causes disease in boys.

Cystic fibrosis is said to be "linked" to another gene if A. CFTR is part of an operon that includes the other gene. B. CFTR and the other gene are located near each other on the same chromosome. C. CFTR is translated as a chimera with the other protein. D. both CFTR and the protein product of the other gene are activated when phosphorylated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. E. the function of the other gene requires chloride transport.

CFTR and the voltage-gated calcium channel are similar in that A. both pass calcium ions. B. both are opened by depolarization. C. both are caused to open by an increase in the concentration of an intracellular messenger. D, both are closed when a cytosolic plug enters the channel lumen and blocks it. E. both play a critical role in brain cells.

Cystic Fibrosis ( Edexcel International A Level Biology )

Revision note.

Cystic Fibrosis

- A gene codes for a single polypeptide

- The polypeptide can affect the phenotype, e.g. it could form part of an enzyme or a membrane transport protein

- Genetic disorders are often caused by a mutation in a gene that results in a differently-functioning or non-functioning protein that alters the phenotype of the individual

Cystic fibrosis

- This gene codes for the production of chloride ion channels required for secretion of sweat, mucus and digestive juices

- A mutation in the CFTR gene leads to production of non-functional chloride channels

- This reduces the movement of water by osmosis into the secretions

- The result is that the body produces large amounts of thick, sticky mucus in the air passages, the digestive tract and the reproductive system

- People who are heterozygous won’t be affected by the disorder but are carriers

- People must be homozygous recessive in order to have the disorder

- If both parents are carriers the chance of them producing a child with cystic fibrosis is 1 in 4, or 25 %

- If only one of the parents is a carrier with the other parent being homozygous dominant, there is no chance of producing a child with cystic fibrosis, as the recessive allele will always be masked by the dominant allele

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disorder caused by a recessive allele

The respiratory system

- It prevents infection by trapping microorganisms

- This mucus is moved out of the respiratory tract by cilia

- In people with cystic fibrosis, due to the faulty chloride ion channels, the cilia are unable to move as the mucus is so thick and sticky

- This means microorganisms are not efficiently removed from the lungs and lung infections occur more frequently

- The surface area for gas exchange is reduced which can cause breathing difficulties

- Physiotherapy can support people with cystic fibrosis to loosen the mucus in the airways and improve gas exchange

The digestive system

- Digestion of some food may be reduced and therefore key nutrients may not be made available for absorption

- The mucus can cause cysts to grow in the pancreas which inhibit the production of enzymes , further reducing digestion of key nutrients

- The lining of the intestines is also coated in thick mucus, inhibiting the absorption of nutrients into the blood

The reproductive system

- Mucus is normally secreted in the reproductive system to prevent infection and regulate the progress of sperm through the reproductive tract after sexual intercourse

- In men the tubes of the testes can become blocked, preventing sperm from reaching the penis

- In women thickened cervical mucus can prevent sperm reaching the oviduct to fertilise an egg

You've read 0 of your 0 free revision notes

Get unlimited access.

to absolutely everything:

- Downloadable PDFs

- Unlimited Revision Notes

- Topic Questions

- Past Papers

- Model Answers

- Videos (Maths and Science)

Join the 100,000 + Students that ❤️ Save My Exams

the (exam) results speak for themselves:

Did this page help you?

Author: Naomi H

Naomi graduated from the University of Oxford with a degree in Biological Sciences. She has 8 years of classroom experience teaching Key Stage 3 up to A-Level biology, and is currently a tutor and A-Level examiner. Naomi especially enjoys creating resources that enable students to build a solid understanding of subject content, while also connecting their knowledge with biology’s exciting, real-world applications.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The association between cystic fibrosis-related diabetes and periodontitis in adults: A pilot cross-sectional study

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Oral Health Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States of America, Department of Dental Health Sciences, School of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Oral Health Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States of America

Roles Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Periodontics, Dental School, University of Texas Health at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, United States of America, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States of America

Affiliation Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology, and Nutrition, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Oral Health Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States of America, Department of Health Systems and Population Health, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States of America

- Alaa A. Alkhateeb,

- Lloyd A. Mancl,

- Kathleen J. Ramos,

- Marilynn L. Rothen,

- Georgios A. Kotsakis,

- Dace L. Trence,

- Donald L. Chi

- Published: June 25, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305975

- Reader Comments

Periodontitis is a highly prevalent complication of diabetes. However, the association between cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) and periodontitis has not yet been evaluated. The objective of this study was to assess if: 1) CFRD is associated with periodontitis among adults with CF, and 2) periodontitis prevalence differs by CF and diabetes status.

This was a pilot cross-sectional study of the association between CFRD and periodontitis in adults with cystic fibrosis (CF) (N = 32). Historical non-CF controls (N = 57) from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) dataset were frequency matched to participants with CF on age, sex, diabetes status, and insulin use. We defined periodontitis using the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Periodontology (CDC/AAP) case definition, as the presence of two or more interproximal sites with CAL ≥3 mm and two or more interproximal sites with PD ≥4 mm (not on the same tooth) or one site with PD ≥5 mm. Because NHANES periodontal data were only available for adults ages ≥30 years, our analysis that included non-CF controls focused on this age group (CF N = 19, non-CF N = 57). Based on CF and diabetes status, we formed four groups: CFRD, CF and no diabetes, non-CF with diabetes, and non-CF and no diabetes (healthy). We used the Fisher’s exact test for hypotheses testing.

There was no association between CFRD and periodontitis for participants with CF ages 22–63 years (CFRD 67% vs. CF no diabetes 53%, P = 0.49), this was also true for those ages ≥30 years (CFRD 78% vs. CF no diabetes 60%, P = 0.63). For the two CF groups, the prevalence of periodontitis was significantly higher than for healthy controls (CFRD 78% vs. healthy 7%, P<0.001; CF no diabetes 60% vs. healthy 7%, P = 0.001) and not significantly different than the prevalence for non-CF controls with diabetes (CFRD 78% vs. non-CF with diabetes 56%, P = 0.43; CF no diabetes 60% vs. non-CF with diabetes 56%, P = 0.99).

Among participants with CF, CFRD was not associated with periodontitis. However, regardless of diabetes status, participants with CF had increased prevalence of periodontitis compared to healthy controls.

Citation: Alkhateeb AA, Mancl LA, Ramos KJ, Rothen ML, Kotsakis GA, Trence DL, et al. (2024) The association between cystic fibrosis-related diabetes and periodontitis in adults: A pilot cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 19(6): e0305975. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305975

Editor: Tanay Chaubal, International Medical University, MALAYSIA

Received: April 11, 2023; Accepted: June 7, 2024; Published: June 25, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Alkhateeb et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: We are not able to share participant data because they contain potentially identifying or sensitive patient information. Data are available by contacting the Office of Research ( [email protected] ) at the University of Washington School of Dentistry for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Funding: A.A.A: the University of Washington Dental Hygiene Education Fund (Grant Number: N/A), and Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University (Grant Number: N/A). M.L.R: The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (Grant Number: UL1 TR002319). K.J.R: The National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Grant Number: K23HL138154). D.L.C: The University of Washington Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Research Development Program (Grant Number: SINGH19R0), the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disorders Cystic Fibrosis Research Translation Center Clinical Core (Grant Number: NIH P30 DK089507), the U.S. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (Grant Number: K08DE020856), the Dr. Douglass L. Morell Dentistry Research Fund University of Washington School of Dentistry (Grant Number: N/A). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) is a unique type of diabetes mellitus (DM) that shares similarities with major DM types [ 1 , 2 ]. CFRD affects up to 50% of adults with cystic fibrosis (CF) and adversely impacts the respiratory health, nutritional status, quality of life, and survival of individuals with CF [ 1 , 3 , 4 ]. DM complications like retinopathy and nephropathy occur in CFRD but with less frequency and severity than in other DM types [ 2 ].

Periodontitis, defined as the inflammation of hard tissues supporting the teeth, is commonly associated with DM [ 5 ]. Potential biological mechanisms linking DM and periodontitis include periodontal bacteria triggering a host defense response, which increases diabetes-induced systemic inflammation and leads to periodontal tissue destruction [ 6 ]. The prevalence and severity of periodontitis are both significantly higher in U.S. adults with DM than those without DM [ 5 ]. In addition, studies have shown that hyperglycemia (poorly controlled DM) is associated with increased colonization of periodontal bacteria and poorer periodontal treatment outcomes [ 7 , 8 ]. Despite the strong links between DM and periodontitis [ 9 ], there are no studies on whether CFRD has an impact on the periodontal health of adults with CF.

In addition to CFRD, adults with CF present with several additional risk factors for periodontitis, such as increased systemic inflammation because of frequent respiratory infections, inhaled treatments, bone disease, anxiety, and depression [ 10 – 12 ]. It is unknown if CF modifies the association between diabetes and periodontitis. In this study, we tested the following hypotheses: 1) CFRD is associated with periodontitis, and 2) periodontitis prevalence differs by CF and diabetes status.

Materials and methods

Study design and study population.

This was a cross-sectional pilot study with a historical control group. Adults with CF were recruited from the Adult CF Center at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, U.S.A, from November 2019 to June 2021. We recruited English-speaking adults with CF who were able to provide written informed consent. There were four exclusion criteria. First, to decrease risk of infection for adults with CF, we excluded adults with active infection with Burkholderia cenocepacia or Mycobacterium abscessus in the prior two years (N = 23). Second, to avoid confounding in the association between diabetes and periodontitis, we excluded adults with pulmonary exacerbation requiring intravenous antibiotics or systemic steroids in the prior 4 weeks (N = 15). Third, smoking is a known risk factor for periodontitis. Because smoking is rare among adults with CF, we excluded adults with a history of smoking (N = 7). Fourth, we excluded adults with CF with no history of an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) in the last two years (N = 41). Finally, to avoid risk of endocarditis, we excluded adults who needed prophylactic antibiotics for dental visits (N = 4) (S1 Fig in S1 File ).

A historical control group without CF was identified from the 2013–2014 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) dataset which included periodontal examination data for participants ages ≥30 years. Thus, our control group consisted of individuals from this age group. NHANES participants were included if they had complete documentation of periodontal examinations, laboratory tests for diabetes, medical history questions for diabetes, and interviews assessing demographics (S2 Fig in S1 File ). We excluded NHANES participants with impaired glucose tolerance and smokers. NHANES does not include a variable for CF. Thus, to avoid including adults with CF from NHANES in our control groups, we excluded NHANES participants who reported chronic obstructive respiratory diseases and chronic bronchitis. Non-CF controls were frequency matched three to one to participants with CF on age, sex, diabetes status, and insulin use.

We collected identifiable data from participants (e.g., medical record numbers). These data were saved in encrypted password-protected files and only the primary investigator had access to these data. The data were de-identified after completing the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington (protocol number: 00007976).

Recruitment of participants with CF

We obtained a HIPAA waiver of consent from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington to allow for a medical record screening to identify eligible adults with CF. Adults with CF were recruited by phone, email, or in person during their routine CF clinic visits. We scheduled a two-hour study visit at the dental research clinic at the University of Washington School of Dentistry. We followed the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation infection control protocols during the study visit. We obtained a written informed consent and HIPAA authorization from participating adults with CF at the study visit to allow for subsequent abstraction of medical record data. Informed consent and HIPAA authorization were documented using RedCap™. The informed consent procedure was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington. Participants with CF with unmet dental treatment needs were provided a referral to the University of Washington dental clinics. We provided oral hygiene instructions, an oral hygiene kit with a toothbrush and fluoridated toothpaste, and $95 as reimbursement for transportation and compensation for the participant’s time.

There were four study procedures: 1) survey, 2) periodontal screening, 3) medical record abstraction, and 4) control data procurement.

We designed a 17-item survey ( S1 Table in S1 File ). The survey included questions on sociodemographic factors (race, ethnicity, household income, education level, dental insurance), history of dental care utilization, and personal oral hygiene habits. We designed the survey using REDCap™ [ 13 ] and participants used a study iPad to complete the survey.

Periodontal screening.

Each participant received a full-mouth periodontal screening conducted by a trained and calibrated registered dental hygienist [ 14 ]. The periodontal screening included a full-mouth assessment of periodontal pocket depth (PD) and gingival margin level using a manual UNC-15 periodontal probe. These two periodontal measures were assessed at six sites per tooth for all teeth present, excluding third molars [ 15 ]. PD was defined as the distance in millimeters (mm) from the free gingival margin to the bottom of periodontal sulcus. Gingival margin level was defined as the distance in mm from the free gingival margin to the cementoenamel junction. Clinical attachment loss (CAL) was calculated by subtracting gingival margin level from PD using the following equation: CAL = PD–(+/–) gingival margin level. All measurements were rounded to the lowest whole mm [ 15 ].

Medical record abstraction for participants with CF.

For participants with CF, we abstracted sociodemographic and medical data from electronic medical records to generate study variables. Data included age, sex, health insurance type, CF-transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) genotype, most recent forced expiratory volume in one second percent predicted (FEV 1 % predicted), any previous referral for lung transplant evaluation, CFRD status, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), and CFTR modulator therapy use. CFTR modulator therapy was defined as triple CFTR modulator therapy (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor), other CFTR modulator therapy (ivacaftor, lumacaftor/ ivacaftor, or tezacaftor/ ivacaftor), or none.

Control data procurement.

For non-CF controls in the 2013–2014 NHANES, we obtained sociodemographic data (age, sex, race, ethnicity, income level, education level), medical data (diabetes status, HbA1c, BMI), and periodontal measures (PD, CAL). Periodontal measures were collected from NHANES using the same protocol used for participants with CF described above [ 16 ].

Outcome measure

Our outcome was periodontitis [yes/no]. We defined periodontitis using the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Periodontology (CDC/AAP) case definition [ 17 ], as the presence of two or more interproximal sites with CAL ≥3 mm and two or more interproximal sites with PD ≥4 mm (not on the same tooth) or one site with PD ≥5 mm.

Comparison groups

Participants with CF were divided into two groups (those with CFRD, and all others). CFRD was defined based on an established diagnosis by a physician following the American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria using an OGTT of 200 mg/dL or greater or HbA1c greater than 6.5%. All others had a normal OGTT within the last two years. Non-CF controls were also divided into two groups (non-CF with diabetes and non-CF without diabetes), with diabetes status defined based on self-reported diabetes and HbA1c. Thus, there were four comparison groups: CFRD, CF and no diabetes, non-CF with diabetes, and non-CF with no diabetes (healthy).

Data analysis

We generated descriptive statistics and reported means and standard deviations (SD) for normally distributed quantitative variables, medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for non-normally distributed quantitative variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. We presented descriptive data for all participants with CF and for participants with CF divided into CFRD status (yes/no). We also presented descriptive data for study groups with and without CF ages 30 years and older grouped by diabetes status. To test for differences in the study variables, we used the independent samples t-test for normally distributed quantitative variables, the Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed quantitative variables, the Fisher’s exact test for binary variables, and the exact chi-square test for categorical variables.

For hypothesis testing, first, we used the Fisher’s exact test to assess the association between CFRD and periodontitis for all enrolled participants with CF ages 22–63 years. Second, we used the independent samples t-test to assess differences in means of clinical periodontal measures (PD, CAL) between participants with CF grouped by CFRD status. Third, we used the Fisher’s exact test to compare the prevalence of periodontitis in participants ages 30 years and older across the four comparison groups (CFRD, CF and no diabetes, non-CF with diabetes, and healthy). Fourth, we used the Welch’s analysis of variance with the Games-Howell post hoc test to assess for between groups differences in PD and CAL for the four comparison groups and adjusted for multiple testing. We reported the difference in means and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Alpha was set at 0.05 and all tests were two-sided. Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 19.0 for Mac.

Participants with CF by diabetes status

Participants with CF with and without diabetes did not differ in sociodemographic characteristics ( Table 1 ). Compared to participants in the CF group without diabetes, those with CFRD had a higher median HbA1c (median: CFRD 6.2% vs. CF no diabetes 5.4%, P<0.001). There were no other differences in other medical and behavioral characteristics between the two CF groups.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305975.t001

Non-CF controls

Compared to non-CF controls, the CF group ages 30 years and older had a higher proportion of white participants (CF 100% vs. non-CF 67%, P = 0.038) ( Table 2 and S2 Table in S1 File ); a lower proportion of participants with an annual income of less than $70,000 (CF 17% vs. non-CF 52%, P = 0.013); and a lower median BMI (CF 23.4 kg/m 2 vs. non-CF 28.4 kg/m 2 , P = 0.002).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305975.t002

Periodontitis and CFRD in participants with CF.

CFRD was not associated with periodontitis (CFRD 67% vs. CF no diabetes 53%, P = 0.49) ( Table 3 ). Participants with CF with and without diabetes had similar means of clinical periodontal measures (PD: CFRD 2.4±0.11 mm vs. CF no diabetes 2.4±0.13 mm, P = 0.58), (CAL: CFRD 1.8±0.33 mm vs. CF no diabetes 1.7±0.28 mm, P = 0.18).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305975.t003

Periodontitis and CF-Diabetes status.

The prevalence of periodontitis for the two CF groups, with and without diabetes, ages 30 years and older were significantly higher than the prevalence of periodontitis for the healthy control group (CFRD 78% vs. healthy 7%, P<0.001; CF no diabetes 60% vs. healthy 7%, P = 0.001) ( Table 4 ) and not significantly different than the prevalence of periodontitis for the non-CF control group with diabetes (CFRD 78% vs. non-CF with diabetes 56%, P = 0.43; CF no diabetes 60% vs. non-CF with diabetes 56%, P = 0.99).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305975.t004

Compared to healthy controls, both CF groups had significantly deeper PD (CFRD vs. healthy: mean difference = 1.3, 95CI% = 1.1,1.5, P<0.001; CF no diabetes vs. healthy: mean difference = 1.3, 95CI% = 1.1,1.5, P<0.001), and significantly greater CAL (CFRD vs. healthy: mean difference = 0.66, 95CI% = 0.30,1.0, P<0.001; CF no diabetes vs. healthy: mean difference = 0.51, 95CI% = 0.23,0.80, P<0.001) ( Table 5 ). The two CF groups had significantly deeper PD than non-CF controls with diabetes (CFRD vs. non-CF with diabetes: mean difference = 0.91, 95CI% = 0.60,1.2, P<0.001; CF no diabetes vs. non-CF with diabetes: mean difference = 0.90, 95CI% = 0.58,1.2, P<0.001), but similar CAL (CFRD vs. non-CF with diabetes: mean difference = 0.09, 95CI% = -0.66,0.52; P = 0.97; CF no diabetes vs. non-CF with diabetes: mean difference = -0.06, 95CI% = -0.62,0.50, P = 0.99).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305975.t005

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the association between CFRD and periodontitis and to include non-CF controls in the assessment of periodontal health of adults with CF. There were two main findings. First, the prevalence of periodontitis did not differ by CFRD status among participants with CF. Second, both CF groups (with and without diabetes) ages 30 years and older had higher prevalence of periodontitis than healthy controls and similar prevalence of periodontitis to non-CF controls with diabetes, despite adults with CF having higher socioeconomic status than non-CF controls.

First, CFRD was not associated with periodontitis among participants with CF in our study. This finding is inconsistent with studies of non-CF adults with DM that showed increased prevalence and severity of periodontitis in DM [ 5 , 18 ]. There are three potential interconnected explanations for our findings. First, periodontitis is associated with poorly controlled diabetes. Studies have shown that the prevalence and severity of periodontitis increased with HbA1c values of 8.0% and higher [ 19 ]. Overall, our CFRD group had well-controlled diabetes. Only two participants with CFRD had an HbA1c value higher than 8.0% and two-thirds of participants with CFRD had HbA1c of less than 6.5%. Second, temporary hyperglycemia occurs in the absence of CFRD for adults with CF, which is mainly related to steroid treatment of pulmonary exacerbations [ 1 , 4 , 20 ]. Studies of non-CF adults showed that prediabetes, indicated by glucose level that is higher than normal but lower than diabetes level, was associated with increased periodontitis [ 8 ]. Fluctuations in blood glucose levels in adults with CF without diabetes might have mitigated the difference in periodontitis by CFRD status in our study. Third, most of our study participants were white, had relatively high socioeconomic status, had dental insurance, maintained optimal oral hygiene and reported frequent utilization of preventive dentistry, all of which are factors that are protective against periodontitis [ 18 , 21 ]. Future studies of CFRD and periodontal health should include a more diverse population with CF including non-whites, lower socioeconomic status, and more severe CFRD. Collecting longitudinal data could help account for the impact of steroid use and episodes of hyperglycemia.

Second, regardless of their CFRD status, participants with CF had higher prevalence of periodontitis than healthy controls and similar prevalence of periodontitis to non-CF controls with diabetes, despite having higher socioeconomic status than non-CF controls. There are two potential explanations. First, adults with CF without diabetes are at higher risk for prediabetes than non-CF adults without diabetes [ 20 ], which potentially increased their risk for periodontitis. Participants with CF without diabetes in our study had significantly higher median HbA1c values than healthy controls ( S3 Table in S1 File ). Increased HbA1c is independently associated with increased periodontitis in the general population [ 5 ]. However, increased HbA1c by itself does not fully explain the difference in the prevalence of periodontitis in our study, as participants with CF without diabetes had a significantly lower HbA1c than participants with CFRD who had a significantly lower HbA1c than non-CF controls with diabetes, yet the three groups had similar prevalence of periodontitis. Another potential explanation is that CF modifies the risk of periodontitis. The impact of increased HbA1c on the periodontal health for participants with CF might have been amplified by other risk factors for periodontitis like increased systemic inflammation associated with frequent lung infections, frequent use of inhaled medications, and the presence of other comorbidities like asthma, bone disease, anxiety, and depression [ 10 – 12 , 22 ]. Larger longitudinal studies with concurrent controls are needed to measure the impact of glucose fluctuation and confirm if CF modifies the risk of periodontitis as suggested by our findings.

Our study showed that regardless of their CFRD status participants with CF are at similar risk of periodontitis as non-CF adults with diabetes, a well-defined high-risk group for periodontitis. This is particularly concerning for adults with CF because periodontitis is linked to poor diabetes control and increased systemic inflammation, both of which are risk factors for poor CF outcomes [ 23 – 25 ]. In addition, studies have showed risk of micro-aspiration of oral bacteria and links between oral infections and decreased lung function in individuals with lung diseases [ 26 – 28 ].

There are two important considerations in the interpretation of periodontitis prevalence by CF status in our study. First, while individuals in the two CF groups had a higher prevalence of periodontitis than healthy controls, individuals in all three groups had mild to moderate periodontitis ( S3 Table in S1 File ). Second, while the non-CF controls were from a nationally representative data source, individuals in the non-CF groups are not representative of all adults enrolled in NHANES. For example, the non-CF groups did not include older adults (≥65 years) and adults with a history of smoking, two population subgroups at increased risk for periodontitis. According to the latest NHANES analyses, about one-half of the U.S. population had periodontitis with increased risk among smokers, individuals with obesity, and adults with severe diabetes, most of whom are not likely to be represented in our non-CF control groups [ 5 , 29 , 30 ].

Collectively, our findings call for strategies to ensure optimal oral health for adults with CF. Strategies should focus on increasing oral health awareness and facilitating dental care access, as well as conducting further clinical research. First, oral health awareness for adults with CF can be improved by integrating oral health promotion as part of the CF care during clinic visits and at community level. Routine CF care should include promotion of oral health by conducting regular dental screenings and discussions of the importance of optimal oral health to the maintenance of general health and quality of life. CF advocacy groups have demonstrated successes in promoting health related practices for individuals with CF [ 31 ]. These organizations can partner with dentists and dental hygienists to promote efforts to build resources and provide education to meet the oral health needs of adults with CF. In hospital settings with dental clinics, pairing dental visits with the routine CF care visits might be an efficient way to increase dental care utilization for adults with CF. As part of dental care, behavioral interventions like motivational interviewing could be utilized with the goal of defining barriers to optimal oral health and ways to mitigate the potential impact of CF and related treatments on oral health. Finally, the current literature is inadequate to generate evidence-based dental care recommendations specific for adults with CF. There is a need for longitudinal multicenter studies with a representative sample of all adults with CF to build a framework of CF-related risk factors for dental diseases that would guide clinical care recommendations.

There were four main limitations to our study. First, the study had limited power because of small sample size. Recruitment and clinical data collection were adversely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, the time of diabetes screening for adults without CFRD was not uniform in our study. We identified adults with CF without diabetes based on a normal OGTT result from the past two years. Episodes of glucose abnormality are common in adults with CF without diabetes, proposing a potential confounder in the association between diabetes and periodontitis that we did not account for in this study [ 20 ]. We opted for the two-year time for an OGTT due to the low adherence to annual OGTT that has been demonstrated in the CF population [ 32 ]. Of the 90 individuals excluded from our study, 41 individuals did not have OGTT in the last two years. In addition, adults with CF who had completed the recommended regular OGTT, and as a result were eligible to participate in our study, were likely to be different in terms of behavioral factors than those who did not adhere to the recommended regular OGTT. This biased our study population toward a CF population with high adherence to health-related behaviors which may have also been reflected in their periodontal health status. It is possible that rates of periodontitis are higher among those individuals who have not undergone routine OGTT screening. Future studies should use a standardized approach to define CF adults without diabetes, potentially with continuous glucose monitoring at the time of dental evaluation. Third, to avoid confounding in the association between diabetes and periodontitis, we excluded individuals with CF who were treated with steroids for pulmonary exacerbations in the last 4 weeks. Thus, our study did not include individuals with advanced CF disease who experience frequent pulmonary exacerbations which biased our study population toward a healthier CF population. Fourth, we conducted our study at a single site, and we had a historical control group. Most of our study population was white, high-income, and had dental insurance, all of which are factors associated with a lower risk of periodontitis [ 18 ]. Future studies should focus on recruiting a more diverse study population, especially across race, ethnicity, and income.

In conclusion, among adults with CF, CFRD was not associated with periodontitis. However, CF is a potential risk factor for periodontitis as our study groups with CF had higher prevalence of periodontitis than healthy controls and similar prevalence of periodontitis as non-CF controls with diabetes–a well-defined high-risk group for periodontitis. There is a need for larger, multicenter, longitudinal studies with concurrent control group to understand how CF-related comorbidities and treatments impact the periodontal health of adults with CF. These data could be used to update dental care recommendations for adults with CF and to develop interventions aimed at improving the oral and systemic health and the quality of life of this vulnerable population.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. plos one alkhateeb strobe-checklist-cross-sectional..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305975.s001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305975.s002

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff at the Regional Clinical Dental Research Center, the UW adult CF center, and the UW Cystic Fibrosis Research Center for their help in completing this project.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

The Biology Corner

Biology Teaching Resources

Case Study – Effects of Coyote Removal in Texas

Examine data from an experiment where coyotes were removed from test sites. Evaluate the effects on rodents and mesopredators.

Case Study – The Genetics of Eye Color

A case study exploring the genetics of eye color. Students review a pedigree and examine the role of HERC2 and OCA2 in eye color inheritance.

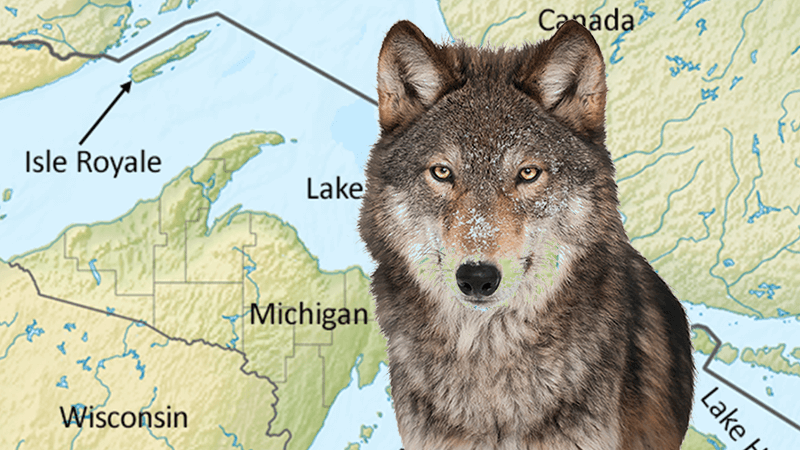

Ecology Case Study – The Wolves of Isle Royale

Case study explores the interactions of wolves and moose on Isle Royale. Students examine data on population growth and spinal deformities caused by inbreeding.

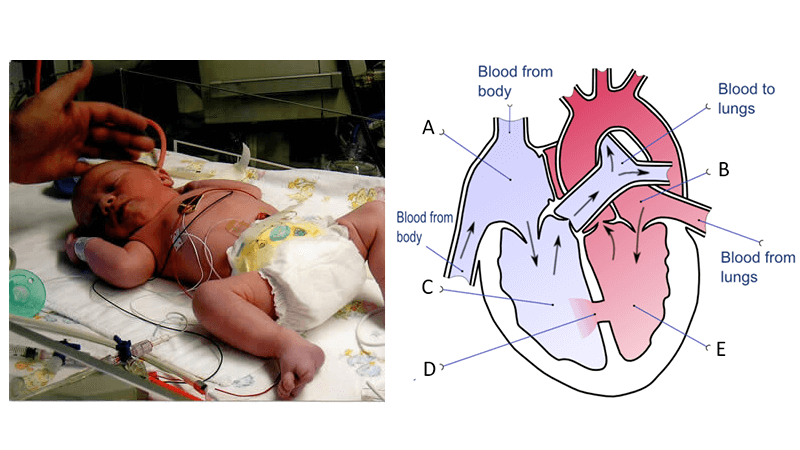

Updated Case – A Tiny Heart (Ross Procedure)

Case study exploring a heart defect in a newborn. Baby Lucas first undergoes balloon dilation to improve blood flow and later has his valve replaced.

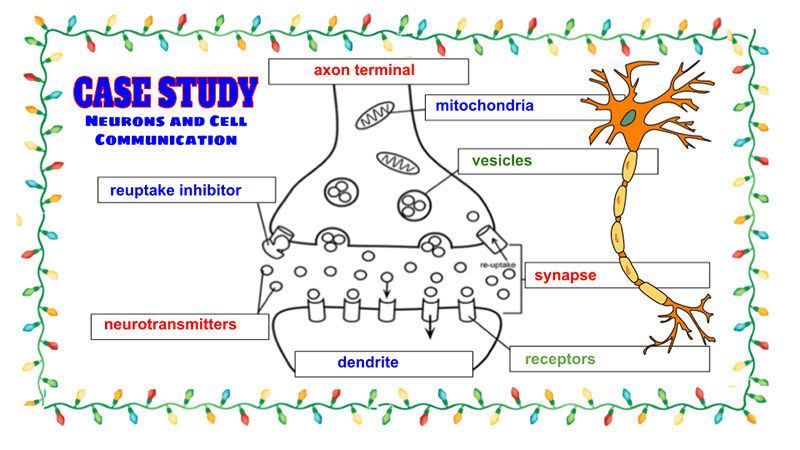

Case Study: Neurons and Cell Communication

A case study for anatomy students to learn about neurons and multiple sclerosis. Students read the case, label diagrams, and answer questions.

Case Study – How Human Activities Affect Water Quality

Use the data to determine where a river is most polluted, and determine what factors affect the composition of the water, like locations near towns or farms.

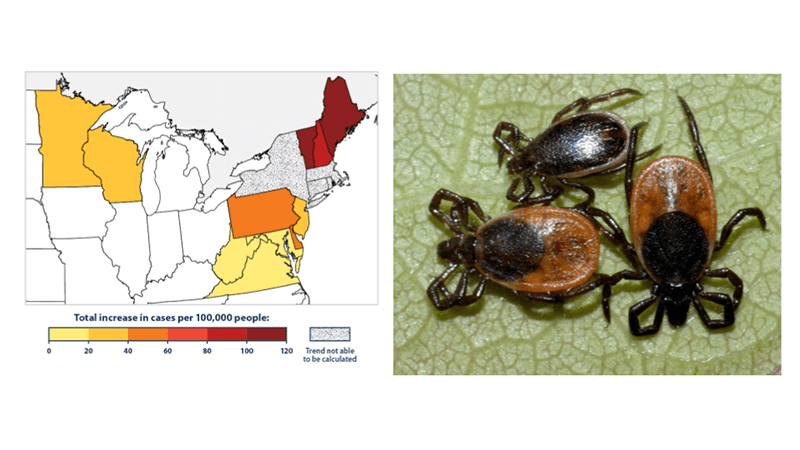

Bullseye – A Medical Case Story for Biology

A basic biology case story about ticks and Lyme disease. Learn the anatomy of a tick and how the tick transmits a bacteria that causes disease.

Gaucher Disease is a Lysosome Storage Disorder

This mini-case study explores Gaucher disease, a lysosome storage disorder where cells are unable to clear harmful waste products.

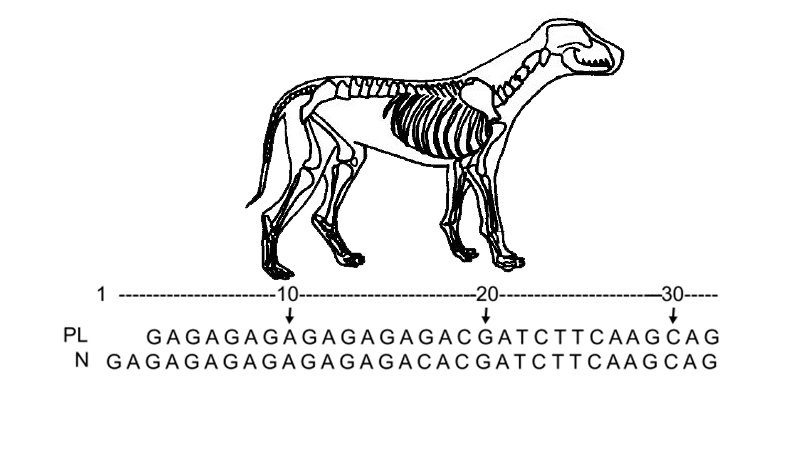

Case Study: Dogs, SNPs, and Patellar Luxation

Students learn how a genetic polymorphism (SNP) is associated with a common problem in chihuahua dogs where their patella slips out of position.

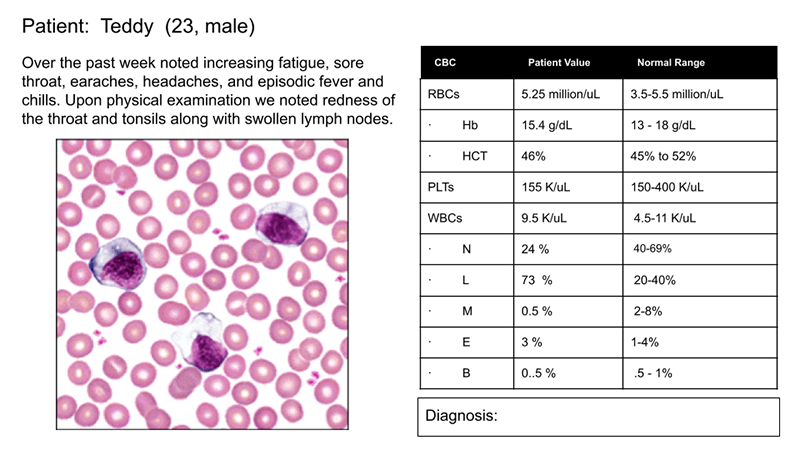

Blood Case Studies for Anatomy (Hematology)

Examine blood slides in this interactive activity. Students determine the disorder illustrated in the slides, sickle cell, leukemia, malaria.

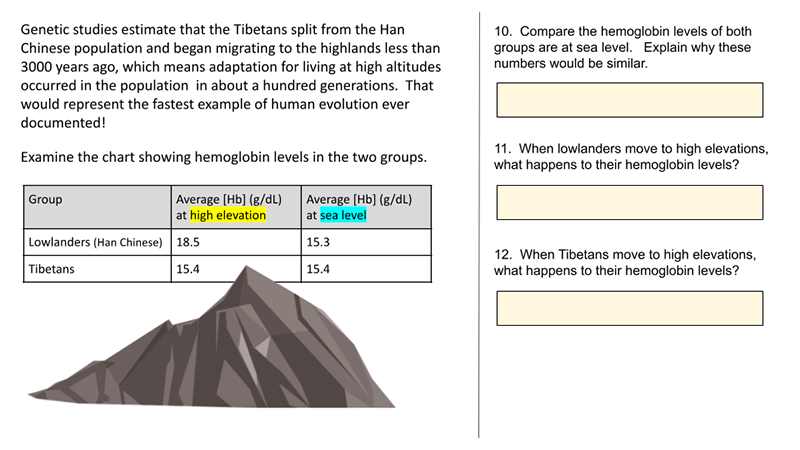

Case Study – Tibetans and Altitude (Remote)

This case study is a remote alternative to “How Do Tibetans Survive High Altitudes.” The remove version is shorter and does not require as much guidance by the instructor. I created this version with Google slides, so students can type their answers directly onto the slide. I made remote versions of several activities because I…

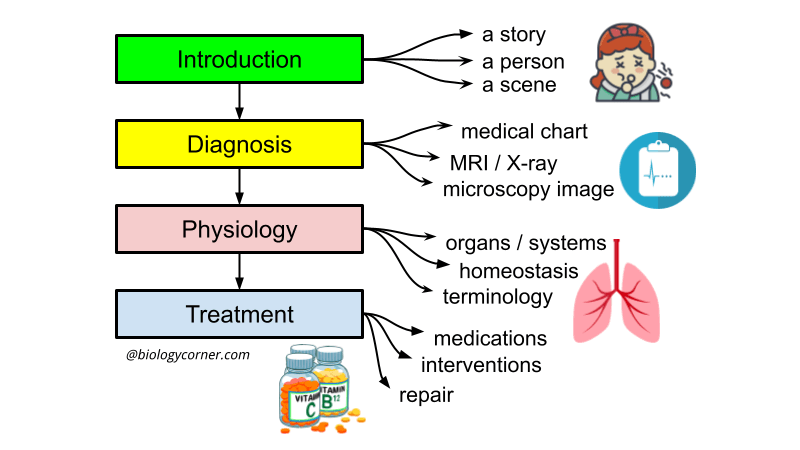

Student Designed Case Studies for Anatomy

Anatomy project where students create their own case study focusing on a disease of their choice. Template included with list of possible topics.

Case Study – Celiac Disease and Digestion

Case study explores the role of villi in the digestive system as student learn how gluten triggers the immune system in people with celiac disease.

Case Study: Cystic Fibrosis Mutations

This case study is a follow-up to the Cystic Fibrosis Case Study where students explore how changes in transport proteins affects the movement of ions, resulting in a build-up of chloride ions and the symptoms of the disease. Students were introduced to the idea that different mutations can cause differences in the transport proteins, but…

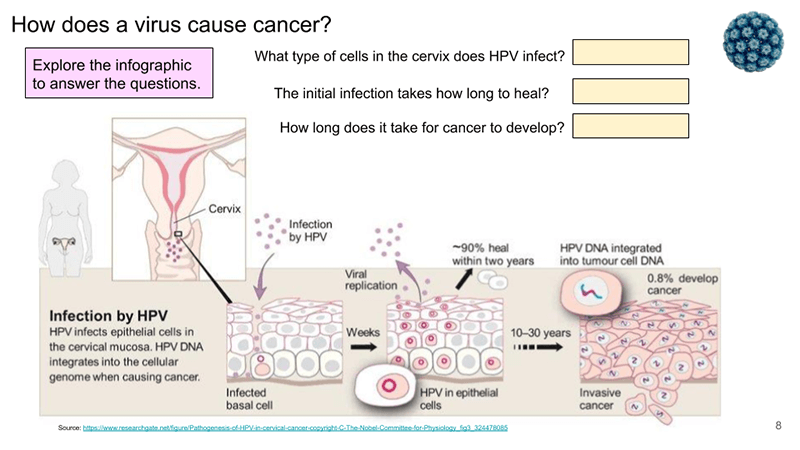

Case Study – Mitosis, Cancer, and the HPV Vaccine

Students in my anatomy class get a quick review of the cell and mitosis. This activity on HPV shows how the cell cycle relates to overall health. In fact, many of the chapters in anatomy have anchoring phenomena on diseases and health. For example, cystic fibrosis is a cellular transport problem, but has serious effects…

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Insights into aspergillus fumigatus colonization in cystic fibrosis and cross-transmission between patients and hospital environments.

1. Introduction

2. materials and methods, 2.1. fungal isolates, 2.2. microbiological identification, 2.3. molecular identification, 2.4. microsatellites, 2.5. screening of cyp51a point mutations, 2.6. sequencing of cyp51a gene, 2.7. broth microdilution test (bmd), 3.1. isolates identification and microsatellite genotyping, 3.2. screening and detection of cyp51a point mutations, 4. discussion, 5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Pilewski, J.M.; Frizzell, R.A. Role of CFTR in airway disease. Physiol. Rev. 1999 , 79 (Suppl. S1), S215–S255. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Elborn, J.S. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2016 , 388 , 2519–2531. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Bergeron, C.; Cantin, A.M. Cystic Fibrosis: Pathophysiology of Lung Disease. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019 , 40 , 715–726. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Burgener, E.B.; Moss, R.B. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators: Precision medicine in cystic fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2018 , 30 , 372–377. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Coutinho, H.D.; Falcão-Silva, V.S.; Gonçalves, G.F. Pulmonary bacterial pathogens in cystic fibrosis patients and antibiotic therapy: A tool for the health workers. Int. Arch. Med. 2008 , 1 , 24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Schwarz, C.; Eschenhagen, P.; Bouchara, J.P. Emerging Fungal Threats in Cystic Fibrosis. Mycopathologia 2021 , 186 , 639–653. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Warris, A.; Bercusson, A.; Armstrong-James, D. Aspergillus colonization and antifungal immunity in cystic fibrosis patients. Med. Mycol. 2019 , 57 (Suppl. S2), S118–S126. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Latgé, J.P. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999 , 12 , 310–350. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Poore, T.S.; Meier, M.; Towler, E.; Martiniano, S.L.; Brinton, J.T.; DeBoer, E.M.; Sagel, S.D.; Wagner, B.D.; Zemanick, E.T. Clinical characteristics of people with cystic fibrosis and frequent fungal infection. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2022 , 57 , 152–161. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lattanzi, C.; Messina, G.; Fainardi, V.; Tripodi, M.C.; Pisi, G.; Esposito, S. Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis in Children with Cystic Fibrosis: An Update on the Newest Diagnostic Tools and Therapeutic Approaches. Pathogens 2020 , 9 , 716. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Burgel, P.R.; Paugam, A.; Hubert, D.; Martin, C. Aspergillus fumigatus in the cystic fibrosis lung: Pros and cons of azole therapy. Infect. Drug Resist. 2016 , 9 , 229–238. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Amin, R.; Dupuis, A.; Aaron, S.D.; Ratjen, F. The effect of chronic infection with Aspergillus fumigatus on lung function and hospitalization in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest 2010 , 137 , 171–176. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Vanhee, L.M.; Symoens, F.; Bouchara, J.P.; Nelis, H.J.; Coenye, T. High-resolution genotyping of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates recovered from chronically colonized patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008 , 27 , 1005–1007. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- de Valk, H.A.; Klaassen, C.H.; Yntema, J.B.; Hebestreit, A.; Seidler, M.; Haase, G.; Müller, F.-M.; Meis, J.F. Molecular typing and colonization patterns of Aspergillus fumigatus in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2009 , 8 , 110–114. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- de Valk, H.A.; Klaassen, C.H.; Meis, J.F. Molecular typing of Aspergillus species. Mycoses 2008 , 51 , 463–476. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Balajee, S.A.; de Valk, H.A.; Lasker, B.A.; Meis, J.F.; Klaassen, C.H. Utility of a microsatellite assay for identifying clonally related outbreak isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus . J. Microbiol. Methods 2008 , 73 , 252–256. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- van der Linden, J.W.; Camps, S.M.; Kampinga, G.A.; Arends, J.P.; Debets-Ossenkopp, Y.J.; Haas, P.J.; Rijnders, B.J.A.; Kuijper, E.J.; van Tiel, F.H.; Varga, J.; et al. Aspergillosis due to voriconazole highly resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and recovery of genetically related resistant isolates from domiciles. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013 , 57 , 513–520. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Ahmad, S.; Joseph, L.; Hagen, F.; Meis, J.F.; Khan, Z. Concomitant occurrence of itraconazole-resistant and -susceptible strains of Aspergillus fumigatus in routine cultures. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015 , 70 , 412–415. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Mavridou, E.; Mortensen, K.L.; Snelders, E.; Frimodt-Moller, N.; Khan, H.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Verweij, P.E. Development of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus during azole therapy associated with change in virulence. PLoS ONE 2010 , 5 , e10080. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Snelders, E.; Huis In ’t Veld, R.A.; Rijs, A.J.; Kema, G.H.; Melchers, W.J.; Verweij, P.E. Possible environmental origin of resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus to medical triazoles. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2009 , 75 , 4053–4057. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Snelders, E.; Camps, S.M.; Karawajczyk, A.; Schaftenaar, G.; Kema, G.H.; van der Lee, H.A.; Klaassen, C.H.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Verweij, P.E. Triazole fungicides can induce cross-resistance to medical triazoles in Aspergillus fumigatus . PLoS ONE 2012 , 7 , e31801. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Burgel, P.R.; Baixench, M.T.; Amsellem, M.; Audureau, E.; Chapron, J.; Kanaan, R.; Honoré, I.; Dupouy-Camet, J.; Dusser, D.; Klaassen, C.H.; et al. High prevalence of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in adults with cystic fibrosis exposed to itraconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012 , 56 , 869–874. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- van Ingen, J.; van der Lee, H.A.; Rijs, A.J.; Snelders, E.; Melchers, W.J.; Verweij, P.E. High-Level Pan-Azole-Resistant Aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015 , 53 , 2343–2345. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Fuhren, J.; Voskuil, W.S.; Boel, C.H.; Haas, P.J.; Hagen, F.; Meis, J.F.; Kusters, J.G. High prevalence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from high-risk patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015 , 70 , 2894–2898. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Chen, J.; Li, H.; Li, R.; Bu, D.; Wan, Z. Mutations in the cyp 51A gene and susceptibility to itraconazole in Aspergillus fumigatus serially isolated from a patient with lung aspergilloma. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005 , 55 , 31–37. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Chowdhary, A.; Kathuria, S.; Randhawa, H.S.; Gaur, S.N.; Klaassen, C.H.; Meis, J.F. Isolation of multiple-triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains carrying the TR/L98H mutations in the cyp 51A gene in India. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012 , 67 , 362–366. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Snelders, E.; Karawajczyk, A.; Schaftenaar, G.; Verweij, P.E.; Melchers, W.J. Azole resistance profile of amino acid changes in Aspergillus fumigatus CYP 51A based on protein homology modeling. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010 , 54 , 2425–2430. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Chong, G.L.; van de Sande, W.W.; Dingemans, G.J.; Gaajetaan, G.R.; Vonk, A.G.; Hayette, M.P.; van Tegelen, D.W.E.; Simons, G.F.M.; Rijnders, B.J.A. Validation of a new Aspergillus real-time PCR assay for direct detection of Aspergillus and azole resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015 , 53 , 868–874. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Trabasso, P.; Matsuzawa, T.; Arai, T.; Hagiwara, D.; Mikami, Y.; Moretti, M.L.; Watanabe, A. Development and validation of LAMP primer sets for rapid identification of Aspergillus fumigatus carrying the cyp 51A TR(46) azole resistance gene. Sci. Rep. 2021 , 11 , 17087. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Arai, T.; Majima, H.; Watanabe, A.; Kamei, K. A Simple Method To Detect Point Mutations in Aspergillus fumigatus cyp 51A Gene Using a Surveyor Nuclease Assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020 , 64 , 10–1128. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rodrigues, E.G.; Lirio, V.S.; Lacaz Cda, S. Preservation of fungi and actinomycetes of medical importance in distilled water. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 1992 , 34 , 159–165. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Lacaz, S.C.; Porto, E.; Martins, J.E.C.; Heinz-Vacari, E.M.; Takahashi de Melo, N. Tratado de Micologia Médica. 9 ; Sarvier: São Pauloo, Brazil, 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Balajee, S.A.; Houbraken, J.; Verweij, P.E.; Hong, S.B.; Yaghuchi, T.; Varga, J.; Samson, R. Aspergillus species identification in the clinical setting. Stud. Mycol. 2007 , 59 , 39–46. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Pontes, L.; Beraquet, C.A.G.; Arai, T.; Pigolli, G.L.; Lyra, L.; Watanabe, A.; Moretti, M.L.; Schreiber, A.Z. Aspergillus fumigatus Clinical Isolates Carrying CYP 51A with TR34/L98H/S297T/F495I Substitutions Detected after Four-Year Retrospective Azole Resistance Screening in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020 , 64 , 10–1128. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Mellado, E.; Diaz-Guerra, T.M.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Rodriguez-Tudela, J.L. Identification of two different 14-alpha sterol demethylase-related genes ( cyp 51A and cyp 51B) in Aspergillus fumigatus and other Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001 , 39 , 2431–2438. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- CLSI M38-A3 ; Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi Approved Standard—Second Edition. CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017; p. 13.

- King, J.; Brunel, S.F.; Warris, A. Aspergillus infections in cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. 2016 , 72 , S50–S55. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Noni, M.; Katelari, A.; Dimopoulos, G.; Doudounakis, S.E.; Tzoumaka-Bakoula, C.; Spoulou, V. Aspergillus fumigatus chronic colonization and lung function decline in cystic fibrosis may have a two-way relationship. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015 , 34 , 2235–2241. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]