Why is Singapore’s school system so successful, and is it a model for the West?

Honorary Professor, The University of Queensland

Disclosure statement

David Hogan received funding from the National Institute of Education in Singapore to conduct the research on which this article draws .

University of Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

For more than a decade, Singapore, along with South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Finland, has been at or near the top of international leagues tables that measure children’s ability in reading, maths and science. This has led to a considerable sense of achievement in Finland and East Asia and endless hand-wringing and head-scratching in the West.

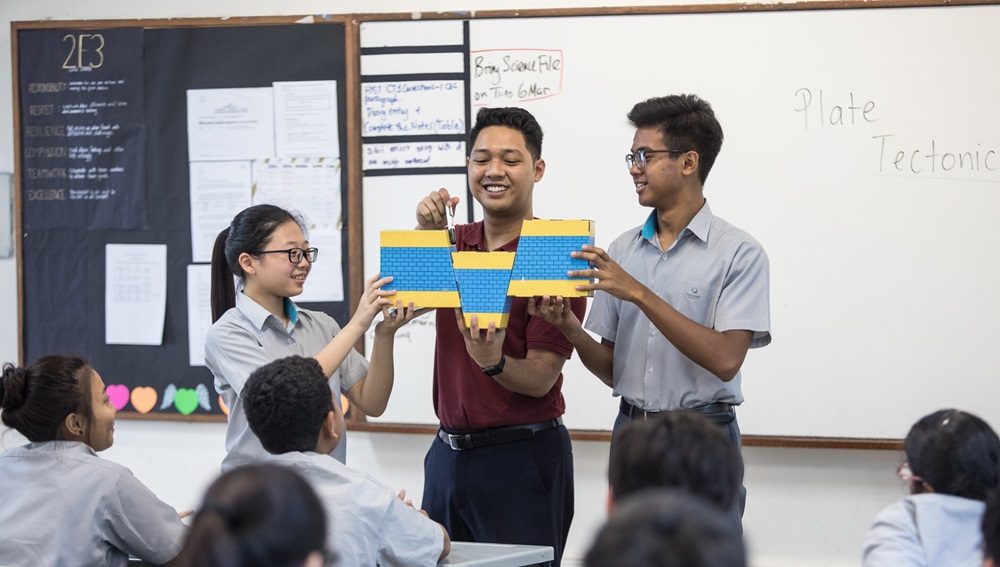

What then do Singaporean teachers do in classrooms that is so special, bearing in mind that there are substantial differences in classroom practices between – as well as within – the top-performing countries? What are the particular strengths of Singapore’s instructional regime that helps it perform so well? What are its limits and constraints?

Is it the right model for countries seeking to prepare students properly for the complex demands of 21st century knowledge economies and institutional environments more generally? Is Singapore’s teaching system transferable to other countries? Or is its success so dependent on very specific institutional and cultural factors unique to Singapore that it is folly to imagine that it might be reproduced elsewhere?

Singapore’s instructional regime

In general, classroom instruction in Singapore is highly-scripted and uniform across all levels and subjects. Teaching is coherent, fit-for-purpose and pragmatic, drawing on a range of pedagogical traditions, both Eastern and Western.

As such, teaching in Singapore primarily focuses on coverage of the curriculum, the transmission of factual and procedural knowledge, and preparing students for end-of-semester and national high stakes examinations.

And because they do, teachers rely heavily on textbooks, worksheets, worked examples and lots of drill and practice. They also strongly emphasise mastery of specific procedures and the ability to represent problems clearly, especially in mathematics. Classroom talk is teacher-dominated and generally avoids extended discussion.

Intriguingly, Singaporean teachers only make limited use of “high leverage” or unusually effective teaching practices that contemporary educational research (at least in the West) regards as critical to the development of conceptual understanding and “learning how to learn”.

For example, teachers only make limited use of checking a student’s prior knowledge or communicating learning goals and achievement standards. In addition, while teachers monitor student learning and provide feedback and learning support to students, they largely do so in ways that focus on whether or not students know the right answer, rather than on their level of understanding.

So Singapore’s teaching regime is one primarily focused on the transmission of conventional curriculum knowledge and examination performance. And clearly it is highly-effective, helping to generate outstanding results in international assessments Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) .

The logic of teaching in Singapore

Singapore’s education system is the product of a distinctive, even unique, set of historical, institutional and cultural influences. These factors go a long way to help explain why the educational system is especially effective in the current assessment environment, but it also limits how transferable it is to other countries.

Over time, Singapore has developed a powerful set of institutional arrangements that shape its instructional regime. Singapore has developed an education system which is centralised (despite significant decentralisation of authority in recent years), integrated, coherent and well-funded. It is also relatively flexible and expert-led.

In addition, Singapore’s institutional arrangements is characterised by a prescribed national curriculum. National high stakes examinations at the end of primary and secondary schooling stream students according to their exam performance and, crucially, prompt teachers to emphasise coverage of the curriculum and teaching to the test. The alignment of curriculum, assessment and instruction is exceptionally strong.

Beyond this, the institutional environment incorporates top-down forms of teacher accountability based on student performance (although this is changing), that reinforces curriculum coverage and teaching to the test. Major government commitments to educational research (£109m between 2003-2017) and knowledge management are designed to support evidence-based policy making. Finally, Singapore is strongly committed to capacity building at all levels of the system, especially the selection, training and professional development of principals and teachers.

Singapore’s instructional regime and institutional arrangements are also supported by a range of cultural orientations that underwrites, sanctions and reproduces the instructional regime. At the most general level, these include a broad commitment to a nation-building narrative of meritocratic achievement and social stratification, ethnic pluralism, collective values and social cohesion, a strong, activist state and economic growth.

In addition, parents, students, teachers and policy makers share a highly positive but rigorously instrumentalist view of the value of education at the individual level. Students are generally compliant and classrooms orderly.

Importantly, teachers also broadly share an authoritative vernacular or “folk pedagogy” that shapes understandings across the system regarding the nature of teaching and learning. These include that “teaching is talking and learning is listening”, authority is “hierarchical and bureaucratic”, assessment is “summative”, knowledge is “factual and procedural,” and classroom talk is teacher-dominated and “performative”.

Clearly, Singapore’s unique configuration of historical experience, instruction, institutional arrangements and cultural beliefs has produced an exceptionally effective and successful system. But its uniqueness also renders its portability limited. But there is much that other jurisdictions can learn about the limits and possibilities of their own systems from an extended interrogation of the Singapore model.

At the same time it is also important to recognise that the Singapore model is not without its limits. It generates a range of substantial opportunity costs, and it constrains (without preventing) the capacity of the system for substantial and sustainable reform. Other systems, contemplating borrowing from Singapore, would do well to keep these in mind.

Reforming the Singapore model

The Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s challenged policy makers to take a long hard look at the educational system that they developed, and ever since they have been acutely aware that the pedagogical model that had propelled Singapore to the top of international leagues table is not appropriately designed to prepare young people for the complex demands of globalisation and 21st knowledge economies.

By 2004-5, Singapore’s government had more or less identified the kind of pedagogical framework it wanted to work towards, and called it Teach Less, Learn More . This framework urged teachers to focus on the “quality” of learning and the incorporation of technology into classrooms and not just the “quantity” of learning and exam preparation.

While substantial progress has been made, the government has found rolling-out and implementing these reforms something of a challenge. In particular, instructional practices proved well entrenched and difficult to change in a substantial and sustainable way.

This was in part because the institutional rules that govern classroom pedagogy were not altered in ways that would support the proposed changes to classroom teaching. As a consequence, well-established institutional rules have continued to drive teachers to teach in ways that prioritise coverage of the curriculum, knowledge transmission and teaching to the test over “the quality” of learning, or to adopt high-leverage instructional practices.

Indeed, teachers do so for good reason, since statistical modelling of the relationship between instructional practices and student learning indicates that traditional and direct instructional techniques are much better at predicting student achievement than high leverage instructional practices, given the nature of the tasks students are assessed on.

Not the least of the lessons of these findings is that teachers in Singapore are unlikely to cease teaching to the test until and unless a range of conditions are met. These include that the nature of the assessment tasks will need to change in ways that encourages teachers to teacher differently. Above all, new kinds of assessment tasks that focus on the quality of student understanding are likely to encourage teachers to design instructional tasks. These can provide rich opportunities to learn and encourage high-quality knowledge work.

The national high stakes assessment system should also incorporate a moderated, school-based component that allows teachers to design tasks that encourage deeper learning rather than just “exam learning”.

The national curriculum should allow substantial levels of teacher mediation at the school and classroom level. This needs to have clearly specified priorities and principles, backed up by substantial commitments to authentic, in-situ, forms of professional development that provide rich opportunities for modelling, mentoring and coaching.

Finally, the teacher evaluation system needs to rely far more substantially on accountability systems that acknowledge the importance of peer judgement, and a broader range of teacher capacities and valuable student outcomes than the current assessment regime currently does.

Meanwhile, teachers will continue to bear the existential burden of managing an ongoing tension between what, professionally speaking, many of them consider good teaching, and what, institutionally speaking, they recognise is responsible teaching.

One of the central challenges confronting the Ministry of Education in Singapore is to reconcile good and responsible teaching. But the ministry is clearly determined to bed-down a pedagogy capable of meeting the demands of 21st century institutional environments, particularly developing student capacity to engage in complex knowledge work within and across subject domains.

The technical, cultural, institutional and political challenges of doing so are daunting. However, given the quality of leadership across all levels of the system, and Singapore’s willingess to grant considerable pedagogical authority to teachers while providing clear guidance as to priorities, I have no doubt it will succeed. But it will do so on its own terms and in ways that achieve a sustainable balance of knowledge transmission and knowledge-building pedagogies that doesn’t seriously compromise the overall performativity of the system.

It is already clear that the government is willing to tweak once sacred cows, including the national high stakes exams and streaming systems. However, it has yet to tackle the perverse effects of streaming on classroom composition and student achievement that continues to overwhelm instructional effects in statistical modelling of student achievement.

Towards a knowledge building pedagogy

Singapore’s experience and its current efforts to improve the quality of teaching and learning do have important, if ironic, implications for systems that hope to emulate its success.

This is especially true of those jurisdictions – I have in mind England and Australia especially – where conservative governments have embarked on ideologically driven crusades to demand more direct instruction of (Western) canonical knowledge, demanding more testing and high stakes assessments of students, and imposing more intensive top-down performance regimes on teachers.

In my view, this is profoundly and deeply mistaken. It is also more than a little ironic given the reform direction Singapore has mapped out for itself over the past decade. The essential challenge facing Western jurisdictions is not so much to mimic East Asian instructional regimes, but to develop a more balanced pedagogy that focuses not just on knowledge transmission and exam performance, but on teaching that requires students to engage in subject-specific knowledge building.

Knowledge building pedagogies recognise the value of established knowledge, but also insist that students need to be able to do knowledge work as well as learning about established knowledge. Above all, this means students should acquire the ability to recognise, generate, represent, communicate, deliberate, interrogate, validate and apply knowledge claims in light of established norms in key subject domains.

In the long run, this will do far more for individual and national well-being, including supporting development of a vibrant and successful knowledge economy, than a regressive quest for top billing in international assessments or indulging in witless “culture wars” against modernity and emergent, not to mention long-established, liberal democratic values.

- Education policy

- school curriculum

- Teacher training

Senior Research Development Coordinator

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

- Society ›

- Education & Science

Education in Singapore - statistics & facts

The singapore education system, the pressures of achieving academic excellence, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Mean PISA score of students in Singapore 2009-2018, by subject

Government recurrent expenditure on education Singapore 2013-2022

Mean years of schooling Singapore 2013-2022

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

Educational Institutions & Market

Government total expenditure on education in Singapore FY 2012-2022

Education Level & Skills

Highest education qualification attained by adult residents Singapore 2022

Literacy rate Singaporeans 15 years and older 2012-2021

Related topics

Recommended.

- Education in Indonesia

- Education in Vietnam

- Education in Thailand

- Education in Japan

- Education in China

Recommended statistics

- Premium Statistic Estimated share of government spending in Singapore FY 2022, by ministries

- Premium Statistic Mean PISA score of students in Singapore 2009-2018, by subject

- Premium Statistic Mean years of schooling Singapore 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Highest education qualification attained by adult residents Singapore 2022

- Basic Statistic Literacy rate Singaporeans 15 years and older 2012-2021

Estimated share of government spending in Singapore FY 2022, by ministries

Estimated share of government spending in Singapore in financial year 2022, by ministries

Mean Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) score of students in Singapore from 2009 to 2018, by subject

Mean years of schooling for adults aged 25 years and above in Singapore from 2013 to 2022

Breakdown of residents aged 25 years and older in Singapore in 2022, by highest education qualification attained (in 1,000s)

Literacy rate for people 15 years and older in Singapore from 2012 to 2021

Government spending

- Premium Statistic Government total expenditure on education in Singapore FY 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Government recurrent expenditure on education Singapore FY 2021, by education level

- Premium Statistic Government expenditure on education per student Singapore FY 2022, by education level

Government total expenditure on education in Singapore from financial years 2012 to 2022 (in billion Singapore dollars)

Government recurrent expenditure on education Singapore FY 2021, by education level

Government recurrent expenditure on education in Singapore in the financial year 2021, by education level (in billion Singapore dollars)

Government expenditure on education per student Singapore FY 2022, by education level

Government recurrent expenditure on education per student in Singapore in the financial year 2022, by education level (in 1,000 Singapore dollars)

- Premium Statistic Enrollment in educational institutions in Singapore 2021, by type

- Premium Statistic Enrollment in primary schools in Singapore 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Enrollment in secondary schools in Singapore 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Enrollment in polytechnic institutions in Singapore 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Full-time enrollment in universities in Singapore 2013-2022

Enrollment in educational institutions in Singapore 2021, by type

Enrollment in educational institutions in Singapore in 2021, by type (in 1,000s)

Enrollment in primary schools in Singapore 2013-2022

Enrollment in primary schools in Singapore from 2013 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Enrollment in secondary schools in Singapore 2013-2022

Enrollment in secondary schools in Singapore from 2013 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Enrollment in polytechnic institutions in Singapore 2013-2022

Polytechnic enrollment in Singapore from 2013 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Full-time enrollment in universities in Singapore 2013-2022

Full-time university enrollment in Singapore from 2013 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Educational institutions

- Premium Statistic Number of primary schools in Singapore 1960-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of secondary schools in Singapore 1960-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of mixed level schools in Singapore 1960-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of pre-university schools in Singapore 1970-2022

Number of primary schools in Singapore 1960-2022

Number of primary schools in Singapore from 1960 to 2022

Number of secondary schools in Singapore 1960-2022

Number of secondary schools in Singapore from 1960 to 2022

Number of mixed level schools in Singapore 1960-2022

Number of mixed level schools in Singapore from 1960 to 2022

Number of pre-university schools in Singapore 1970-2022

Number of junior colleges and centralized institutes in Singapore from 1970 to 2022

Teaching staff

- Premium Statistic Number of teachers by educational institution in Singapore 2021

- Premium Statistic Student-teacher ratio in primary schools Singapore 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Average primary school class size Singapore 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Length of service of primary school teachers in Singapore 2022

- Premium Statistic Student-teacher ratio in secondary schools Singapore 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Average secondary school class size Singapore 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Length of service of secondary school teachers in Singapore 2022

Number of teachers by educational institution in Singapore 2021

Number of teachers in Singapore in 2021, by educational institution

Student-teacher ratio in primary schools Singapore 2013-2022

Ratio of students to teaching staff in primary schools in Singapore from 2013 to 2022

Average primary school class size Singapore 2013-2022

Average class size in primary schools in Singapore from 2013 to 2022

Length of service of primary school teachers in Singapore 2022

Length of service of primary school teachers in Singapore in 2022

Student-teacher ratio in secondary schools Singapore 2013-2022

Ratio of students to teaching staff in secondary schools in Singapore from 2013 to 2022

Average secondary school class size Singapore 2013-2022

Average class size in secondary schools in Singapore from 2013 to 2022

Length of service of secondary school teachers in Singapore 2022

Length of service of secondary school teachers in Singapore in 2022

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

- Education sector in the Gulf Cooperation Council

- Education in Myanmar

- Education in India

- Education in Australia

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

You might be interested in...

Preparing our children for the future

In this feature.

What are the new pathways available in Singapore’s education system?

Financial support for Singaporean students at every stage of education

The 2 ways Singapore is making learning enjoyable for students

How is our education system preparing our young for the future?

We use cookies to tailor your browsing experience. By continuing to use Gov.sg, you accept our use of cookies. To decline cookies at any time, you may adjust your browser settings. Find out more about your cookie preferences here .

- Privacy Statement

- Terms of Use

- Rate This Website

- Report Vulnerability

Education in Singapore

People-Making and Nation-Building

- © 2022

- Yew-Jin Lee 0

National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

- Provides wide spectrum of up-to-date information about educational sectors, policies, and school subjects in Singapore

- Contains many scholarly introductions to education in Singapore

- Presents a comprehensive and valuable resource written by select team of local and international experts

Part of the book series: Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects (EDAP, volume 66)

55k Accesses

10 Citations

1 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (23 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

Yew-Jin Lee

The Next Phase of Developments in Singapore’s ECCE: Quality in the Best Interest of All Children?

- Sirene May-Yin Lim, Chee Wah Sum

Inclusive Education for Children with Special Educational Needs in Singapore Schools

- Kenneth K. Poon

Primary and Secondary Education in Singapore: Bringing Out the Best in Every Learner

- Jeanne Ho, Yew-Jin Lee

Post-secondary Education in Singapore

- Trivina Kang

Higher Education in Singapore: Perspectives and Future Orientation

- Horn Mun Cheah, Laura Lyn Lee

Post-secondary Education Institutions Internships—The Singapore Experience

- Shien Chue, Ethan Pang, Priscilla Pang, Yew-Jin Lee

The Dynamic Landscape of Adult Education in Singapore

- Helen Bound, Zan Chen

The Texture and History of Singapore’s Education Meritocracy

- Charleen Chiong

From Meritocracy to Parentocracy, and Back

- Vincent Chua, Kelvin K. C. Seah

Education for the Minority Malay Community in Singapore: A Sociological Perspective

- Mohamad Shamsuri Juhari

The Dynamic Interplay Between Curriculum and Context: Revisions in Response to National, Societal, and Contextual Needs

- Christina Ratnam-Lim Tong Li, Lucy Oliver Fernandez

School Leadership in Decentralized Centralism of Singapore Education

- Salleh Hairon, Soon How Loh

Assessment Reforms in Singapore

- Kelvin Heng Kiat Tan

Chinese Language Education and Assessment Policy in Singapore (1965–2021)

- Yun-Yee Cheong

Key Developments in English Education in Singapore from the Post-independence Period to the Present

- Suzanne S. Choo, Alexius Chia, Caroline Chan

Innovating Towards Reading Excellence in the Singapore English Language Curriculum

- Chin Ee Loh, Elizabeth Pang

Paths to a Whole: Placing Music Education in Singapore

- E. I. Dairianathan

The Coherence Between Policy Initiatives and Physical Education Developments in Nation-Building

- Steven Kwang San Tan, Shern Meng Tan, Connie Huat Neo Yeo, Liang Han Wong

- Singapore Education

- Meritocracy in Singapore

- Bilingualism in Singapore

- Nation-Building

- People-Making

- Physical Education

- Geography Education

- Art Education

About this book

Editors and affiliations, about the editor, bibliographic information.

Book Title : Education in Singapore

Book Subtitle : People-Making and Nation-Building

Editors : Yew-Jin Lee

Series Title : Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-9982-5

Publisher : Springer Singapore

eBook Packages : Education , Education (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2022

Hardcover ISBN : 978-981-16-9981-8 Published: 07 April 2022

Softcover ISBN : 978-981-16-9984-9 Published: 08 April 2023

eBook ISBN : 978-981-16-9982-5 Published: 06 April 2022

Series ISSN : 1573-5397

Series E-ISSN : 2214-9791

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : X, 437

Number of Illustrations : 6 b/w illustrations, 10 illustrations in colour

Topics : Educational Policy and Politics , International and Comparative Education , History of Education

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

School Education System In Singapore

Overview of the Education System in Singapore

The education system in Singapore is governed by the Ministry of Education’s “Desired Outcomes of Education” at primary, secondary and post-secondary levels. Generally, Singapore’s education system aims to create students with a good sense of self-awareness, sound moral compass and the necessary skills and knowledge to face obstacles in the future. After graduating from the system, students in Singapore should be confident critical thinkers, self-directed learners, active contributors to society and concerned citizens with a strong sense of civic consciousness.

Current Structure and Format

Education is compulsory for all Singaporean citizens and consists of six years of primary school, four years of secondary school, and one to three years of post-secondary school. On the other hand, kindergarten is optional — preschool education is offered by the Ministry of Education as well as private providers. The curriculum’s structure and syllabus is well-developed and is assessed with an end-of-course exam. Students in the fourth year of primary school are subjected to school-based tests that determine what level (band) they will study for English, mathematics, mother tongue, and science in the next two years. At the end of primary school, students aged 12 years old are required to sit for the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) in English, mathematics, mother tongue, and science. Students are admitted to one of four pathways in secondary school based on their PSLE results.

Singapore Education Facts

English is used as the language of instruction for most subjects. Students will also study their ‘mother tongue’ language from an early age. The Singapore primary school curriculum develops students’ proficiency in English, their mother tongue language (Chinese, Malay and Tamil speaking students) and mathematics.

In secondary school, the curriculum is standardised for students aged 12 to 16 even though they enter different bands. Students in the more difficult bands are expected to perform at a higher level and achieve better academic results. Core subjects at secondary school are English, mother tongue language, mathematics, science, literature, history, geography, arts, crafts and design; and technology and home economics. Secondary school students will sit for the GCE O and N Levels to determine which type of post-secondary education they will pursue. The GCE A levels determine a student’s path in higher education.

The academic year in the Singapore education system is made up of two semesters. The first semester typically runs from January through to May, followed by a school break. The second semester starts in July, which runs until a break in November and December. Students also enjoy a shorter break in the middle of each semester.

Private and Public Schools in Singapore

There are several types of schools in Singapore. Government schools offer high-quality education with affordable fees. Government-aided schools follow the national syllabus and are mostly funded by the government. Independent schools have more flexibility in determining its fees and curriculum. In addition, there are specialised independent schools that cater to students with skills in mathematics, science, arts and sports, among others. Lastly, there are specialised schools that offer an experiential and hands-on learning approach to learning.

Teachers in Singapore

There are now over 50,000 teachers in Singapore’s education system. Teachers are responsible for performing continuous assessments of their students at all levels of education. Singaporean teachers follow the Singapore Teaching Practice as a model of teaching and learning to deliver effective results to their students. The Ministry of Education provides ongoing training to teachers through the Singapore Instructional Mentoring Programme, Teacher Work Attachment Programme, and Outstanding Educator-in-Residence Programme. In addition, teachers also organise learning communities and conferences to share the latest developments in pedagogy, curriculum, and assessment.

Average Cost of Education in Singapore

The cost of education in Singapore varies depending on the type of institution and level of education. Here is a general overview of the average cost of education in Singapore.

- Early childhood education: The cost can range from around SGD 500 to SGD 2,500 per month for full-day childcare and preschool services.

- Primary and secondary education: Public schools are heavily subsidized by the government with tuition fees typically ranging from SGD 13 to SGD 90 per month.

- Pre-university education: Pre-university education in public schools is also heavily subsidised by the government with fees ranging from SGD 6 to SGD 33 per month.

- Tertiary education: The cost of tertiary education varies depending on the type of institution and the course of study.

However, parents are subjected to small ‘miscellaneous’ fees, which are determined by the Ministry of Education. These fees are in addition to costs for uniforms, transport and school materials.

International Schools in Singapore Fees

Each international school in Singapore has a unique fee structure. Parents can expect to pay anything from USD15,000 to USD30,000 annually for tuition fees. International school fee structures also include registration fees, deposits, technology and maintenance costs.

Government Bodies Involved in Education in Singapore

The Ministry of Education is heavily involved in the country’s curriculum implementation. However, the ministry has been more flexible in recent years — encouraging schools to use the curriculum as a framework and adapt it to fit their students’ needs the best. For example, secondary schools are encouraged to develop additional courses to set them apart from other schools. Therefore, students have more of a direction when it comes to academics by choosing a school that fits their passions and interests.

Education Levels

Children aged three may enter preschools in Singapore. Primary school begins at the age of seven until 12. After that, students transition to secondary school until the age of 17. Students have to complete two or three years of pre-university studies to qualify entrance to the university of their choice.

Singapore education problems

Singapore’s education is known to be one of the best, topping world rankings in standardised tests annually. However, this academic achievement comes at a price. Children as young as seven years old suffer from high stress levels as a result of the competitive pressure from schools, their parents and society as a whole. Many have pointed out that Singapore’s education system focuses too heavily on academics — creating rote learners out of students for the sake of attaining perfect test scores. There is a lack of emphasis on soft skills such as critical thinking and problem solving. This high stakes environment at such a young age may have negative effects on social skills, mental health and physical well-being.

Singapore country stats

Singapore, once a British colonial trading post, is now a wealthy country in Southeast Asia. Over 5.9 million residents live in Singapore. The country is known as a leading financial hub and for its thriving economy. It is renowned for its conservatism and strict local laws and the country prides itself on its stability and security. There are four major languages spoken in Singapore which are English, Mandarin, Malay and Tamil.

Expats living in Singapore information

Singapore is home to over 160,000 expatriates who work in the 7,000 multinational companies operating in the country. International schools in Singapore mainly cater to the children of expatriates who have relocated to the country. It may be difficult for expatriates to enrol their children into local schools as their children need to sit for the Admissions Exercise for International Students (AEIS). Upon passing the AEIS, expatriate children will only be able to enter the local school system if there is a spot available. Only five percent of the total student enrolment in national schools is made up of international students. Strict regulations have also been implemented by the Singaporean government on the enrolment of local students into international schools. Local students need to obtain special permission from the Ministry of Education to gain entr y into international schools.

Standard of living in Singapore

Singapore ranks highly in terms of economy, business climate, technology, and education. Residents of Singapore enjoy high-quality health care, education, personal safety, and housing standards. In addition, residents enjoy a safe and enriched high standard of living due to Singapore's economic status, cleanliness, and multicultural environment.

Public transportation in Singapore

The public transportation system in Singapore is efficient and well-planned. This includes the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) which covers most of Singapore, the Light Rapid Transit and monorail systems. Other options include ferries, public buses, and taxis. Due to limited road space, driving in Singapore can seem like a luxury, and there are many rules and regulations to follow when owning a car.

Visa for family and students in Singapore

There is a wide range of visa options for those wishing to stay in Singapore for a long period of time. Expatriates can apply for an employment pass whereas the Entrepreneur Pass (EntrePass) is suitable for foreign entrepreneurs wanting to start and operate a new business in Singapore. International students are required to apply for a Student Pass.

- https://ncee.org/what-we-do/center-on-international-education-benchmarking/top-performing-countries/singapore-overview-2/singapore-learning-systems/#:~:text=In%20Singapore%2C%20compulsory%20education%20includes,years%20of%20post%2Dsecondary%20school.&text=Based%20on%20these%20results%2C%20students,four%20pathways%20in%20secondary%20school

- https://beta.moe.gov.sg/education-in-SG/

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-16/singapore-s-expat-numbers-slump-for-second-consecutive-year?leadSource=uverify%20wall

- https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/families/article/2111822/downsides-singapores-education-system-streaming-stress-and

- https://www.expat.com/en/guide/asia/singapore/1054-work-visas-in-singapore.html

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-15961759#:~:text=Singapore%20is%20a%20wealthy%20city,on%20its%20stability%20and%20security

- https://www.mom.gov.sg/working-in-singapore/

- https://www.now-health.com/en/expat-guides/singapore/

- https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/singapore-population/

https://www.moe.gov.sg/education-in-sg/our-schools/types-of-schools

- https://www.ceicdata.com/en/singapore/education-statistics-number-of-students-and-teachers-in-educational-institutions/teachers-total

- Preschool/Kindergarten

- Primary Schools

- Secondary Schools

- Pre-University

- Learning Centre

- Special Education Needs

- CIEB Homepage

- How We Work

- Comparative Data

- International Education News Headlines

- Ongoing Research

top-performing countries

Foundation of Support

Learning system, career and technical education, teachers and principals.

Singapore is an extraordinary success story. Since becoming an independent republic in 1965, it has transformed from an impoverished island with no natural resources and a mostly illiterate population to a country of 5.8 million people whose living standards match those of the most highly-developed industrial nations. From the very beginning, Lee Kuan Yew, the prime minister who led Singapore to this achievement, understood that an educated workforce would be essential to fulfilling his ambitious economic goals.

In 2009, when Singapore participated for the first time in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), the results of Prime Minister Lee’s efforts were already clear. That year, Singapore’s 15-year-olds were among the top performers in all three subjects. In 2015, the nation was first in the world in all three subjects; in 2018, four Chinese provinces outperformed Singapore, but the small island nation continued to outperform every other nation.

At the end of World War II, Singapore implemented the first in a succession of economic development strategies rooted in improved education and training. Since the 1990s, the nation has focused on boosting creativity and capacity for innovation in its students.

In 2004, the government developed the “Teach Less, Learn More” initiative, which moved instruction further away from its early focus on rote memorization and repetitive tasks and toward deeper conceptual understanding and problem-based learning. Educators abandoned the practice of funneling students into ability-based tracks and began sorting them into three different “bands” in secondary school based on their ultimate educational goal. Although students take most of their classes within their bands, they can take classes in other bands depending on their aptitude and interest in a given subject. The goal is to achieve full subject-based banding, with students freely mixing and matching classes from different bands, by 2024.

Singapore’s current priorities for its education system are reflected in the title of its initiative “Every School a Good School.” This set of reforms aims to ensure that all schools have adequate resources to develop customized programs for their students; raise professional standards for teachers; encourage innovation; and foster partnerships between schools and communities. In addition, Singapore launched the “Learn for Life” initiative in 2018 to promote greater flexibility in teaching, learning, and assessment. With more opportunities for self-directed learning in and out of school, Singapore hopes to encourage lifelong learning for all Singaporeans, in ways that bring them satisfaction and meaning.

Despite Singapore’s strong emphasis on educational equity, there remains a large gap between the nation’s highest-performing and lowest-performing students on PISA. This gap, which persists across all three subjects, did narrow somewhat in mathematics and science in the latest round of PISA. In addition, Singapore stands out among OECD countries for its low percentage of low-performing students and high percentage of high-performing students, including a very high percentage of top-performing students with low socioeconomic status. Ten percent of disadvantaged students in Singapore are in the top-performing group compared to an OECD average of three percent.

Quick Facts

Population: 5.98 million Population growth rate: 0.90% Demographic makeup: Chinese 74.2%, Malay 13.7%, Indian 8.9%, other 3.2% Source: CIA World Factbook, 2023

GDP: $578.254 billion GDP per capita: $106,000 (2021 estimate in 2017 dollars) Source: CIA World Factbook, 2023

Unemployment rate: 3.62% Youth unemployment rate: 9.10% Sources: CIA World Factbook, 2023

Services-dominated economy Key services industries: finance Key industrial areas: electronics, chemicals, oil drilling equipment, petroleum refining, biomedical products, scientific instruments, telecommunication equipment, processed food and beverages, ship repair, offshore platform construction, entrepot trade Sources: CIA World Factbook 2021

Postsecondary attainment Ages 25+: 58.3% (2020 est.) Source: World Bank, 2023

Governance Structure

Singapore’s education system is highly centralized. The Ministry of Education oversees kindergarten (ages four to five) through higher education and lifelong learning. The Ministry allocates funding for all schools, sets course syllabi and national examinations, oversees teacher credentialing, manages the teacher and principal evaluation and promotion system, and hires and assigns principals and teachers to schools. Schools are grouped into geographic clusters, each overseen by a superintendent, to provide local support for the Ministry’s policies and initiatives. The cluster superintendents, who are successful former principals, collaborate with principals in their cluster on how to implement the curriculum and which teaching materials to choose from among a set the Ministry approves and strongly encourages teachers to use. The cluster superintendents also facilitate the sharing of resources and best practices between cluster schools.

While the Ministry sets the framework for the educational system, other entities operate within that framework. Independent or semi-autonomous agencies such as the National Institute of Education (teacher training), the Examinations and Assessment Board (national assessments), and the Institute of Technical Education (vocational education) have clearly defined areas of responsibility and work closely with the Ministry.

Planning and Goals

Singapore articulates clear and comprehensive system-wide goals for education. These goals, which the nation revises regularly, emerge from widespread discussion with partners in the system and with the public, as well as from extensive benchmarking of other leading education systems. Singapore structures policy initiatives around its education goals and creates benchmarks to measure progress. For example, in 2013, Singapore held a National Conversation to gather input on a vision for the 2030 education system strategic plan. Goals included improving character and citizenship education, strengthening digital literacy, building more knowledge and understanding of the history and cultures throughout Asia, expanding supports for disadvantaged students, and building more adult education opportunities. In 2022, Singapore launched a year-long initiative to gather public input as part of developing their Forward Singapore road map. Forward Singapore will prioritize equity while reexamining six key pillars of society: empower (economy and jobs), equip (education and lifelong learning), care (health and social support), build (home and living environment), steward (environmental and fiscal sustainability), and unite (Singapore identity).

In addition, Singapore’s leaders monitor educational research and benchmark best practices from around the world so that the system can continue to match the performance of the world’s best.

Education Finance

The Ministry of Education directly funds all schools based on the number of pupils. In addition, all schools receive a set grant (called an Opportunity Fund) to use for their low-income students and students from ethnic minority groups. Although this supplemental funding is distributed by the Ministry, schools can choose how to spend it. The Ministry also provides funding directly to students from low-income families in the form of subsidies, called Financial Assistance Schemes, for educational materials and activities and funds for school meals. In addition, the Ministry in 1970 created the Education Fund, which collects contributions from Singapore residents to both support all students and low-income students through scholarships and by providing textbooks, meals and uniforms for students who need these but do not otherwise qualify for financial assistance.

Accountability

School accountability.

Schools in Singapore conduct annual self-evaluations of their practices and outcomes using the Ministry-developed School Excellence Model, which includes nine criteria for performance. Schools then develop improvement plans based on the results. Additionally, each school is visited by a Ministry-led team of evaluators once every six years; the team typically includes consultants from the Ministry and respected educators, such as university professors and successful school leaders. The visit is intended to validate the self-evaluation, provide feedback to the school and offer support for improvement.

Improvement efforts are organized through Singapore’s school cluster system. Cluster superintendents meet regularly with principals to monitor their improvement efforts. High-performing schools are eligible for awards. The Ministry annually awards schools that demonstrate outstanding achievement in a single year or over a period of years. The highest award, the School Excellence Award, is given to one school each year.

Teacher Accountability

Singapore uses the Enhanced Performance Management System (EPMS) to conduct annual teacher evaluations. EPMS assesses teachers’ performance based on 16 different competencies, including their work in the classroom and their interaction with the greater school community. Teachers first conduct a self-appraisal, and then supervisors evaluate them against the EPMS. These evaluations are qualitative and consist of written feedback rather than numeric scores of specific indicators. Teachers base their professional development plans on EPMS feedback. Principals, alongside the School Staff Developer (in charge of professional learning) and the Cluster Superintendent, co-construct a “Current Estimated Potential” for each teacher using the results of the EPMS. This estimate, or snapshot of the teacher’s short-term career trajectory, is shared with the teacher and used to help them articulate their career goals. Teachers can earn rewards based on EPMS results, including honors and salary bonuses. The Ministry also selects teachers for awards and recognition at the national level.

Supports for Young Children and Their Families

Singapore has several policies in place to support families with children. Working mothers are entitled to 16 weeks of paid maternity leave if their child is a Singapore citizen and they have worked at their company for at least three months. Otherwise, they are entitled to 12 weeks of maternity leave. Fathers are entitled to two weeks of paternity leave. Working parents also receive six days of paid childcare leave per year if their child is under 7 years of age.

In 2008 the government adopted the Enhanced Marriage and Parenthood Package, which includes a “Baby Bonus,” providing cash awards for each child, and a Child Development Account (CDA), providing dollar-for-dollar matching of parent contributions to an account that can be used for health care, childcare, and other purposes. The government also makes an initial grant contribution to each child’s CDA.

Singapore provides universal health care to citizens. The primary form of support is government subsidies, which cover 80 percent of the cost of care in hospitals and clinics. These subsidies are supplemented by the “3Ms”—Medisave, a mandatory savings program; Medishield, catastrophic health insurance; and Medifund, an endowment to support health care for low-income families. In 2013, the government set up Medifund Junior, which provides support for low-income children, and extended the fund’s benefits to include primary care, dental services, prenatal care, and delivery.

In 2016, Singapore piloted KidSTART, which partners with hospitals and community organizations to provide supports for low-income families, including home visits, developmental screenings and referrals, and parent education, from pregnancy until children reach age 3. KidSTART is now a permanent program.

Childcare for children up to age 4 is privately run in Singapore, but the government has taken steps to ensure care remains affordable for all families. In 2009 Singapore created the Anchor Operator scheme (AOP), which provides subsidies to participating centers with a requirement that they cap fees. The government expanded the AOP in 2014, and in 2016 added the Partner Operator scheme (POP) to subsidize additional centers. The government also sets aside 30 percent of childcare slots for low-income families and directly subsidizes their fees. Parents also can use funds from Child Development Accounts to pay for childcare.

Supports for School Aged Children

All students in Singapore receive an Edusave account, to which the government contributes funds so that it can invest in their future. Families can draw on these accounts for any type of educational expense; disadvantaged students receive additional funding. The Ministry of Education also provides financial assistance for students from low-income families. The aid supports school fees and other expenses for students in government or government-aided private schools. Financial aid for independent schools is also available.

These supports are available in the context of a broader safety net for children. The government’s Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) administers ComCare, which provides cash grants to low- and moderate-income families on a sliding scale. It also covers long-term assistance needed for care and school-related expenses for children of disabled parents. The MSF also oversees the National Council of Social Service, an umbrella group of 450 private organizations that provide services to Singapore citizens. Services include school-based social work and support for students at risk of dropping out of school.

In Singapore, children ages three through six can attend either a public or private kindergarten or a childcare center. Formerly, the Ministry of Social and Family Development oversaw childcare centers while the Ministry of Education oversaw kindergartens. But in 2013, the government created the Early Childhood Development Agency (ECDA) to coordinate oversight of all early childhood education.

Most childcare centers and kindergartens in Singapore are privately run but licensed by ECDA. A subset of centers caps their enrollment fees in exchange for government subsidies, part of a national effort to increase access to childcare for low- and middle-income Singaporeans. Beginning in 2013, the government opened a small number of public kindergartens to model quality programming and further expand access to early education. In 2017, the Prime Minister announced plans for a fourfold increase in the number of public kindergartens by 2025. To ensure public kindergartens are accessible for all families, the Ministry of Education reserves one-third of the total slots for students whose families earn under a certain income level.

ECDA regulates programs for children ages 4-6 as well as programs for younger children. Data from program inspections are not publicly available. ECDA established the Singapore Preschool Accreditation Framework (SPARK) to accredit centers. Accreditation is voluntary, but there are incentives to participate, including access to government subsidies and to professional development for staff. As of 2017, 40 percent of centers in Singapore had attained SPARK certification. Of these, about 10 percent have also attained SPARK commendation, a mark of especially strong teaching and learning practices.

ECDA has developed the Nurturing Early Learners Kindergarten Curriculum Framework as suggested guidance for children ages four to six. The government does not assess learning outcomes for students in kindergarten or childcare; the first nationwide screening of children’s literacy and numeracy skills takes place in the first month of primary school. A new program—called Mission I’mPossible 2—establishes interdisciplinary school-based teams to screen children in childcare for developmental issues starting at two months old.

Primary and Secondary Education

System structure.

In Singapore, the system includes six years of primary school, followed by four to six years of secondary school, and one to three years of postsecondary school. The curriculum for primary schools is common for all students in years one to four. For years five and six, students can take individual courses at the foundation or standard level. Foundational level courses are designed to provide more support for students. As they enter secondary school, students, their parents, and their teachers jointly agree on one of three bands or “streams” they will join: Express, Normal (Academic), and Normal (Technical). All streams offer the same course of study, but Express is accelerated and Normal (Technical) offers more applied work. In most cases, students’ scores on the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) are the primary determinant of the stream they will join, but parents and students can advocate for different streams if they demonstrate accelerated learning or need more help. Singapore is piloting and implementing a system under which students choose streams for specific subjects, rather than their overall course of study, a practice known as subject-based banding. For example, a student could pursue a technical stream in mathematics, but an express stream in English. Subject-based banding currently exists in all primary schools, and the goal is to have full subject-based banding in all secondary schools by 2024.

In addition to these options, Singapore has four specialized schools for students who perform poorly on the PSLE. These schools offer foundational coursework in mathematics and literacy, alongside vocational offerings leading to skill certificates and extensive social supports. There are also specialized independent schools that focus on the arts, sports, and mathematics and science. These schools receive public funding and use the MOE curriculum, but have more flexibility in their program offerings.

Students who want to apply to university stay in secondary school for an additional two years to take A-level courses, as part of the Integrated Program. Those who do not do that have multiple postsecondary options: Polytechnics, the Institute of Technical Education (ITE), Junior Colleges, a Polytechnic Foundation program and a small set of Arts Institutions. Students choose their postsecondary school based on their secondary school stream as well as results from the General Certificate of Education (GCE) examinations, described in more detail below. Polytechnics offer three-year diploma programs. Graduates may pursue university education after they earn their Polytechnic diploma without taking A-level exams, if they so choose. ITE offers shorter technical or vocational education programs, through National ITE Certificate (Nitec) aligned courses and work-based learning. Students graduate from ITE with a Nitec or Higher Nitec qualification and can then continue their vocational studies at a polytechnic or at university. They can also stay at ITE and earn a technical or work study diploma, which also allows a pathways to slect university programs. Junior Colleges offer two- or three-year pre-university education, preparing students for the required examinations to enroll in universities or for entry into Polytechnics.

Standards and Curriculum

The Ministry of Education oversees the development of the national curriculum, which includes “Desired Outcomes of Education.” The desired outcomes are student excellence in life skills, knowledge skills, and subject discipline knowledge organized into eight core skills and values: character development, self-management skills, social and cooperative skills, literacy and numeracy, communication skills, information skills, thinking skills and creativity, and knowledge application skills.

The primary school curriculum includes ten subject areas: English, mother tongue language (available for Chinese-, Malay- and Tamil-speaking students), mathematics, science, art, music, physical education, social studies, and character and citizenship education. A coding class was added to the curriculum in 2019. And in 2021, the Ministry introduced an updated character and citizenship education curriculum which focuses on mental health and cyber-wellness and on the establishment of peer support structures within every school, among other topics. For primary students who qualify as gifted, Singapore offers individualized enriched curriculum opportunities.

Secondary education varies depending on school and program type. Students in the express and Normal (academic program) are required to take English, mother tongue language, mathematics, science, and humanities (geography, history, and English literature). For students in the Normal (Technical) program, compulsory subjects include English, mother tongue language, mathematics, computer applications, and social studies. There are electives available for both the Technical and Normal program as well.

The Ministry of Education has been very involved with the implementation of its primary and secondary curriculum. During the shift from rote learning to the current model emphasizing student engagement and creativity, Ministry officials were very “hands-on” in schools. They met regularly with school leaders and developed extensive professional learning opportunities for teachers around the new curriculum. However, in recent years, the Ministry has taken a step back, encouraging schools to consider the curriculum as a framework which they should adapt to their students’ needs. The Ministry also encourages secondary schools to differentiate themselves through theme courses or special programs designed to attract students with shared interests.

Assessment and Qualifications

Teachers perform continuous assessment of their students at all levels of education. On a day-to-day basis, this assessment is informal and based on student work in and out of the classroom. Before 2019, all students in primary school took school-based exams throughout the year and at the end of each year. Since then, Singapore has eliminated mid-year exams. Students in Primary 1 and 2 have no exams and do not receive grades. By removing these exams, the government hopes to shift focus away from grades and competition and toward learning for its own sake.

At the end of primary school, all students take the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) in four subjects: English, math, science, and mother tongue. Students take exams at one of two levels, based on the level of subjects they took in years five and six. In 2021, the Ministry began to update the PSLE scoring process. Going forward, students will be graded based on individual performance in subjects rather than benchmarked against each other. These scores will be translated to Achievement Level tiers, which will help students determine their stream for lower secondary education, as well as which school they will attend. Students send their examination scores to up to six lower secondary schools, ranked in order of preference. The schools then choose their students based in large part on their PSLE rankings. That said, the Ministry also allows some schools to admit students based on their talents in academic areas, sports, or co-curricular activities without factoring in PSLE results, to provide greater diversity in student talents and interests. Since 2018, schools have been able to offer up to 20 percent of their places to students through this process, called direct school admission. The Ministry of Education helps place those students who are not accepted into their schools of choice.

At the secondary level, student take subject-based exams, depending on their band. After four years of study, students take O-level exams in the express and N-level exams in the Normal (Technical) program. Students in the Normal (Academic) program can take the N-level exams after four years of study or the O-level exams after five years. Students who wish to study at university take A-level exams after an additional two years of study.

Starting in 2027, the N- and O-level exams will be replaced by a new comprehensive Singapore-Cambridge Secondary Education Certificate (SEC). Students will have the option of an additional year in secondary school to take more rigorous courses.

Learning Supports

Struggling students .

Despite Singapore’s strong emphasis on equitable funding, the most recent results from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) exposed a large gap between the nation’s highest- and lowest-performing students. However, the gap has been narrowing in mathematics and science, and educators hope to address academic disparities through early diagnosis and intervention of learning issues. Schools screen students at the beginning of first grade for reading and numeracy skills; those who need extra help (approximately 12-14 percent) are taught in small learning support programs to keep them on pace with their peers. As part of this program, the Ministry funds learning specialists at each school who work with these groups of students.

Students who are still struggling when they reach lower secondary school are offered extra time and support to complete their studies, and teachers may recommend they join the Normal (Technical) stream for most subjects. If students show improvement, they can transfer into a faster-paced band. They can also take courses in different bands if they are only struggling with a particular subject.

Special Education

Whenever possible, the government encourages students with special needs to enroll in mainstream schools, either initially or after having met certain benchmarks in special education. Currently, about 80 percent of all students with special needs attend mainstream schools. To help facilitate their integration, learning support specialists known as Allied Educators help students with conditions such as dyslexia or autism. As of 2018, there was at least one Allied Educator in every mainstream primary and public school, a 40 percent increase over the previous five years. The Ministry has also provided specialized training in special education to a designated group of general education teachers within each mainstream school, to create a strong support system for students with special needs; about 15 percent of teachers in mainstream schools had completed this training by 2019. In addition, since 2020 the Ministry has provided all teachers in mainstream schools with access to online professional learning focused on supporting students with special needs.

In 2019, the Ministry implemented two peer mentoring interventions to support students with special needs in mainstream schools. Circle of Friends allows students with social, emotional or behavioral difficulties to meet with their teacher or Allied Educator along with a group of six to eight of their peers. Over five to eight sessions, the students work together to find solutions for the student in difficulty. Facing Your Fears is a similar program designed to support students suffering from anxiety. In this intervention, groups of two to four students meet with facilitators and Allied Educators to learn self-management strategies over 10 weekly sessions.

For students who need more intensive or specialized assistance, Singapore has 19 government-funded special education schools run by 12 social service agencies. These schools serve populations with highly specific needs: the deaf, the blind, students with autism, or those with the most severe cognitive challenges. Special needs education is available through the postsecondary level, where students with intellectual disabilities are prepared for the workforce through special training programs. The government continues to invest in special education and plans to open seven new schools by 2027. These schools serve less than 2 percent of the total student population.

The Ministry allocates extra funds for special needs students at 150 percent or 300 percent of the base per student cost, depending on whether they attend mainstream or special schools. The Ministry increased spending for special schools by 40 percent from 2015 to 2020 and has pledged to continue this increase. The National Council of Social Services also contributes funding to special schools, specifically for additional social supports.

Digital Platforms and Resources

The Student Learning Space (SLS) provides a library of curriculum-aligned, Ministry-curated resources (e.g., lesson plans, videos, assessments) for all grade levels and subjects. The Ministry assigns teams of teachers to work full-time creating these resources, which are continually updated based on feedback from teachers and students (as is the design of the SLS itself). Singapore announced plans for the SLS in 2013, piloted it in 2017, and expanded it to all schools in 2018. Every student in grades 1-12 has an account to access the SLS. Using templates, teachers create lessons by compiling SLS resources or using a mix of SLS resources and their own materials. Students can also access SLS resources on their own, independent of assignments. Teachers can choose to share the lessons they have created with their peers within the SLS.

In 2020, after students shifted to periodic home-based learning in response to the coronavirus pandemic, Singapore decided to make home-based learning via SLS a permanent feature of the education system. Starting in 2021, secondary school students will have up to two days a month of online learning, and all secondary school students will be provided with a device. Singapore plans to pilot online learning strategies in primary schools to determine the best approach to building these skills for younger students. The Ministry believes that students will benefit from having self-directed learning time at home that complements in-person instruction.

Development of the System

Technical and vocational education gained importance in Singapore at the end of World War II when industrialization created a demand for skilled workers. After attaining independence in 1965, Singapore began investing heavily in vocational education in order to support the country’s very ambitious economic development plans. The Ministry of Manpower worked with economic agencies and industry groups to identify critical workplace needs. Those needs, as well as projections of future needs, were used to inform curriculum planning for vocational education. Singapore created polytechnic institutions in the 1960s as the primary vocational training route for Singaporeans.

Singapore founded the Institute of Technical Education (ITE) in 1992, at a time when vocational education was viewed as a “last resort” for weak students; the five existing polytechnics were not desirable educational options. Singapore wanted to revolutionize vocational education. Spread across a set of state-of-the-art campuses, ITE was designed to be a world-class example of how vocational and technological skills could be translated to a knowledge-based economy.

Today, ITE is filled with simulated and real-world workspaces for students to demonstrate their job skills in a wide variety of high-growth industries. Since 1995, enrollment in vocational education has doubled, and vocational students now make up over 60 percent of the cohort who go on to postsecondary education, with about one-third of those students heading to the ITE and two-thirds to polytechnics.

Recently, Singapore has taken further steps to strengthen its vocational education opportunities for youth and adults. Following the recommendations of the ASPIRE (Applied Study in Polytechnics and ITE Review) commission, in 2016 the government launched SkillsFuture, a national lifelong learning effort. ASPIRE envisioned a coherent workforce-development system, beginning in lower secondary school and extending throughout adulthood. For young people, SkillsFuture includes strengthened education and career guidance, “enhanced” internships, more overseas market immersion opportunities, and the development of individual learning portfolios. For those entering the workforce, it includes apprenticeships, known as “Earn and Learn” programs, and credits toward course fees for work skills-related instruction. And for adults, it includes monetary awards for skills courses, subsidies for mid-career professionals pursuing additional coursework, and fellowships. Anchoring the system is a skills framework and set of qualifications, overseen by the SkillsFuture Council, a body led by the deputy prime minister and including leaders from industry, labor, and government. The framework outlines a body of skills in 34 industry sectors.

Governance and System Structure

Singapore’s career and technical education (CTE) offerings take place primarily at the postsecondary level. At the primary and secondary levels, the emphasis is mainly on career exploration and guidance. A career guidance curriculum has been mandatory since 2014, and the Ministry of Education has created a web portal that enables students to examine their own strengths and interests and explore careers that match them. In addition, students pursuing the Normal (Technical) route in secondary school take coursework that prepares them for entrance exams at the Institute of Technical Education (ITE), Singapore’s primary postsecondary CTE institution.

CTE Programs

ITE offers two-year programs leading to a National ITE certificate (Nitec), with the option of an additional advanced program leading to a Higher Nitec certificate. Starting in 2022, the ITE will introduce a new curriculum that allows students to achieve a Nitec and Higher Nitec in a total of three years instead of four. The new curriculum, which will be phased in over time, is designed to prepare graduates with deeper industry-relevant skills for employment and sufficient foundational skills to allow for lifelong learning. ITE programs are offered in six broad areas: Applied and Health Sciences, Business Services, Design and Media, Electronics and ICT, Engineering, and Hospitality. A technical diploma program (similar to an apprenticeship program) was recently added to the ITE program in Culinary Arts and Engineering, as was a work-study diploma that is offered in a range of areas. ITE requires all students to enroll in data analytics courses and to participate in a three- to six-month internship. The ITE has a reputation for producing highly-skilled graduates, and salaries for ITE graduates have become quite high in recent years. In 2018, 76 percent of ITE graduates found employment within six months of completing school, leading more students to see vocational education as a strong choice for future success.

Another route for secondary graduates who want to pursue technical training is the polytechnics, which offer three-year degree programs in technical fields. Polytechnics now offer nearly 150 diploma programs, and, like the ITE, have worked to remain closely connected with industry, growing and changing alongside Singapore’s economy. Students receive a combination of experiential and classroom-based learning. Up to 40 percent of graduates of postsecondary vocational education pursue a university degree. In many cases they are able to transfer enough credits to complete a bachelor’s degree in two years.

Recent Reforms

In 2020, Singapore’s government announced steps to upgrade the SkillsFuture program with the goal of serving a minimum of 15 percent of the country’s working age labor force per year . Most notably, the plan included another round of financial credits for all adults ages 25 and older to use towards continuing education, plus an additional credit for skills training or retraining for adults ages 40 to 60. These credits can be used in addition to any credits issued since 2016. Individuals must use the new credits by 2025, however. Credits apply to more than 8,000 courses offered by polytechnics, ITE, and universities. SkillsFuture also updated its funding framework to prioritize subsidies for courses that teach in-demand skills and provide career advancement opportunities.

The government has also set ambitious goals to more than triple the number of work-study placements by 2025, double job placements for mid-career workers to 5,500 by 2025, and increase the capacity of reskilling programs for mid-career workers. SkillsFuture also introduced several new mid-career transition programs to help workers upskill during the Covid-19 pandemic, some of which have since been made permanent offerings.

Teacher Recruitment

Only one institution—the National Institute of Education (NIE)—is authorized to prepare teachers, and it offers both a master’s degree and a bachelor’s degree route into teaching. In this way, Singapore limits its teacher recruitment only to those students qualified for the country’s rigorous research universities. Each year, Singapore calculates the number of teachers it will need, and opens only that many spots in the training programs. The selection process is competitive: teaching is a highly-regarded profession in Singapore and students in teacher-education programs receive a stipend during their training. On average, only one out of eight applicants is accepted. Typically, successful candidates have scored at the middle or above on Singapore’s challenging A-level exams. The many other steps in the application process include tough panel interviews that focus on the values, skills, and knowledge that make for a good teacher, as well as intensive reviews of the candidate’s academic record and contributions to school and community.

Teaching salaries in Singapore are largely commensurate with those of other professions. Indeed, the Ministry of Education monitors teacher salaries in relation to other professional salaries and adjusts them to ensure they remain competitive. The maximum salary for a lower secondary teacher is twice the GDP per capita. Teacher salaries increase with years of experience. Successful teachers can earn retention bonuses every three to five years as well as performance bonuses, which can be up to 30 percent of their base salary. Eligibility is determined through annual evaluations that also serve as a basis for coaching and mentoring between teachers.

Teacher Preparation and Induction

The National Institute of Education (NIE) is housed in Nanyang Technological University, one of the most prestigious institutions in Singapore’s higher education hierarchy. All primary and secondary teachers are trained at the NIE. During their training, teacher candidates receive a monthly stipend equivalent to 60 percent of a starting teacher salary, and their tuition is covered by the Ministry of Education. Once they have completed training, teachers must commit to three full years on the job.

The undergraduate teacher-education program is a four-year program that includes 22 weeks of practical experience in schools. The graduate program is a 16-month program that includes 10 weeks of practical experience. Students entering the graduate program first attend the Introduction to Teaching program run by the Academy of Singapore Teachers (AST), a professional learning organization run by teachers. Then, to help them gauge their true interest in teaching, prospective candidates spend a few months to a year working in schools as untrained contract teachers before beginning their coursework.

Both undergraduate and master’s programs are guided by the Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century, a framework that states the values, skills, and knowledge (V3SK) needed for teachers. The curriculum for the undergraduate route includes academic studies—the content the teachers will teach—as well as education studies, curriculum studies, and service learning. Undergraduate students also have opportunities to participate in practicums in other countries. By 2026, teacher candidates and in-service teachers at the NIE will be offered courses on using artificial intelligence (AI) in the classroom under the AI@NIE initiative. AI@NIE is a five-year plan to integrate artificial intelligence into Singaporean classrooms based on research conducted by an NIE task force. AI is already being incorporated into classrooms via text-to-speech, speech evaluation, and other instant feedback tools such as grading of writing and math assessments.

After graduation from either the undergraduate and graduate programs, all beginning teachers take part in a two-year induction program led by the AST and funded by the Ministry of Education. During this period, teachers have a reduced teaching load in order to attend classes and work with a trained mentor.